William De Morgan

William Frend De Morgan (* 16. November 1839 in London; † 15. Januar 1917 ebenda) war ein britischer Künstler des Arts and Crafts Movement und Schriftsteller.

Leben

De Morgan wurde in eine Familie französischer Hugenotten geboren. Sein Vater, Augustus De Morgan, war der erste Mathematikprofessor am neu gegründeten University College London. Seine Mutter, Sofia Elizabeth Frend, war eine Frauenrechtlerin, die sich gemeinsam mit Elizabeth Fry am Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts für Gefängnisreformen, Religionsfreiheit und das Frauenwahlrecht einsetzte.

Im Jahre 1859 wurde De Morgan in die Royal Academy Schools aufgenommen. Dort studierte er gemeinsam mit Frederick Walker und Simeon Solomon. Henry Holiday, der zu seinem Bekanntenkreis zählte, stellte ihn dem Künstler und Dichter William Morris vor. Nach dieser Begegnung wendete sich De Morgan der dekorativen Kunst zu und begann, Experimente im Bereich der Glasmalerei zu machen.[1]

Im Jahr 1863 trafen William Morris, William De Morgan und der Maler Edward Burne-Jones zusammen. Da Morris bisher wenig erfolgreich in der Gestaltung von Keramikgegenständen war, übernahm De Morgan die Fliesenproduktion in dessen Betrieb. Bald begann er, eigene Fliesen zu gestalten und arbeitete danach noch viele Jahre lang mit Morris zusammen, mit dem er sich anfreundete.

De Morgan war mit der Malerin Evelyn De Morgan verheiratet, die den sogenannten „präraffaelitischen“ Stil pflegte.

Schaffensphase

- Der Arabische Saal im Leighton House

- Von Frederic Lord Leighton erhielt De Morgan den Auftrag, den arabischen Saal seines Hauses mit den von Lighton während seiner Reisen gesammelten türkischen, persischen und syrischen Fliesen auszustatten.[2] Diesen Saal hatte der Architekt George Aitchison entworfen.[3] Die Arbeit mit der orientalischen Keramik und den vielfältigen Mustern des Nahen Ostens beeinflusste De Morgans späteres Schaffen.[1]

- P&O

- Von der britischen Reederei P&O wurde er in den Jahren 1882 bis 1900 damit beauftragt, das Fliesendekor für die Innenausstattung zwölf neuer Linienschiffe zu gestalten. Die Keramiken stellten beispielsweise fantasievolle Landschaften oder die Städte und Länder der Reiseziele der P&O-Liner dar. Auch für andere Schiffe fertigte De Morgan Entwürfe, zum Beispiel für das Schiff des Zaren Alexander II. von Russland die „Livadia“. Er setzte seine Arbeiten bis 1904 fort, allerdings zum Schluss mit schwindendem Erfolg.[1]

- Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice

- Im Auftrag von George Frederic Watts bzw. von dessen Witwe Mary schuf De Morgan zwischen 1900 und 1905 die ersten 24 Gedenktafeln für das Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice im Postman’s Park in London.[4]

- Keramikarbeiten

- (c) Memorial to John Cranmer Cambridge in Postman's Park by Marathon, CC BY-SA 2.0

Schriften (Auswahl)

Krankheitsbedingt verbrachte De Morgan einige Zeit mit seiner Frau in Florenz. Im Alter von 65 Jahren begann er, Romane zu schreiben, die sich zu Bestsellern entwickelten, sodass er mit dem Erlös den Unterhalt für sich und seine Frau absichern konnte. Als vielseitig kreativer Mensch entwickelte er auch Telegraphencodes, konstruierte neue Töpferöfen, skizzierte Ideen für Mühlen und Siebe, arbeitete an einem neuen Getriebe für Fahrräder und entwickelte sein eigenes System für Geld-Konten.[1]

- Romane

- Joseph Vance. Grosset & Dunlap, New York 1906, OCLC 5107112.

- Alice-for-Short. Henry Holt and Company, New York 1907, OCLC 3282865.

- mit Bruce Rogers: It Never Can Happen Again. Henry Holt and Company, New York 1909, OCLC 364168.

- An Affair of Dishonour H. Frowde, Toronto 1910, ISBN 0-6657-5206-7.

Literatur

- A. M. W. Stirling: William De Morgan and his wife. Henry Holt and Company, New York 1922, OCLC 365096. im Internet Archive – online

- Rob Higgins et al: William de Morgan: Arts and Crafts Potter. Shire Library, 2010, ISBN 978-0-7478-0738-4, S. 64 (englisch).

- William Gaunt, Maxwell David Eugene Clayton-Stamm: William De Morgan. Studio Vista, London 1971, ISBN 0-2897-0141-4.

- William Gaunt, Maxwell David Eugene Clayton-Stamm: William De Morgan: Pre-Raphaelite ceramics. New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, Conn. 1971, ISBN 0-8212-0390-8.

Weblinks

- William De Morgan bei Google Arts & Culture

- William Frend De Morgan auf artmagick.com (Biografie, englisch)

- William De Morgan: An Introduction. auf victorianweb.org (Biografie, englisch)

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b c d William De Morgan auf demorgan.org.uk, zuletzt abgerufen am 29. Juni 2019.

- ↑ Leighton House Museum, zuletzt abgerufen am 29. Juni 2019.

- ↑ History of the House, zuletzt abgerufen am 29. Juni 2019.

- ↑ John Price: Heroes of Postman's Park: Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Victorian London, The History Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0-7509-5643-7, S. 15

| Personendaten | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Morgan, William De |

| ALTERNATIVNAMEN | Morgan, William Frend De (vollständiger Name) |

| KURZBESCHREIBUNG | britischer Künstler |

| GEBURTSDATUM | 16. November 1839 |

| GEBURTSORT | London |

| STERBEDATUM | 15. Januar 1917 |

| STERBEORT | London |

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Photo of Evelyn de Morgan and her husband William De Morgan

Bowl by William de Morgan, circa 1898-1907. Exhibit in the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA.

Autor/Urheber: MicheleLovesArt, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 2.0

England, London

circa 1890 Willame the Morgan, Sand Ends pottery OKS 1975-13

The tile with flower vase is inspired by examples from the Middle East. Willam de Morgan do not copy this, but made his own interpretation.(c) Memorial to John Cranmer Cambridge in Postman's Park by Marathon, CC BY-SA 2.0

Memorial to John Cranmer Cambridge in Postman's Park

(c) Robmcrorie at en.wikipedia, CC BY 3.0

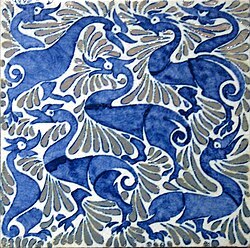

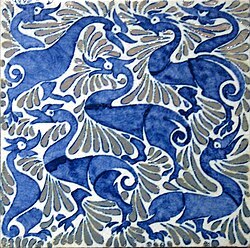

Fantastic ducks on 6-inch tile with lustre highlights, Fulham period, William De Morgan, England