United States Naval Computing Machine Laboratory

Das United States Naval Computing Machine Laboratory (kurz: NCML, deutsch etwa: „Labor für Rechenmaschinen der Kriegsmarine der Vereinigten Staaten“) war während des Zweiten Weltkriegs eine hochgeheime militärische Einrichtung, die sich erfolgreich mit der Entzifferung des verschlüsselten feindlichen Nachrichtenverkehrs der deutschen und der japanischen Kriegsmarine befasste.

Hier wurde die US Navy Cryptanalytic Bombe hergestellt, nach ihrem Entwickler Joseph Desch auch kurz als Desch-Bombe bezeichnet. Sitz des Labors war Gebäude 26 (englisch Building 26) der National Cash Register Company (NCR), eines Herstellers ursprünglich für Registrierkassen, in Dayton (Ohio).

Geschichte

Von besonderer Bedeutung für die Kriegsanstrengungen der Vereinigten Staaten war, nach der am 11. Dezember 1941 erfolgten Kriegserklärung Deutschlands an die USA, die Bekämpfung der deutschen U‑Boote. Diese operierten hauptsächlich im Nordatlantik auf alliierte Geleitzüge. Im Rahmen der dabei benutzten Rudeltaktik war für die deutsche Kriegsmarine eine abhörsichere Funkverbindung zwischen dem Befehlshaber der U‑Boote (BdU) und „seinen“ Booten essentiell. Dazu wurde ein spezielles Schlüsselnetz „Triton“ eingerichtet und innerhalb dessen bis Ende Januar 1942 die Schlüsselmaschine Enigma-M3 (mit drei Walzen) eingesetzt, die zum 1. Februar 1942 durch die kryptographisch stärkere Enigma-M4 (mit vier Walzen) abgelöst wurde.

Die britischen Verbündeten der USA hatten im englischen Bletchley Park unter dem Decknamen „Ultra“ bereits ab Januar 1940 zunächst die von der deutschen Luftwaffe und kurz darauf auch die vom deutschen Heer mit der Enigma I verschlüsselten Nachrichten entziffert. Nach Kaperung des deutschen U‑Boots U 110 (Bild) und Erbeutung einer intakten M3-Maschine und sämtlicher Geheimdokumente (Codebücher inklusive der entscheidend wichtigen Doppelbuchstabentauschtafeln)[3] durch den britischen Zerstörer Bulldog am 9. Mai 1941 gelang ihnen auch der Einbruch in die Marine-Enigma.[4] Als Hilfsmittel verwendeten sie dazu eine vom britischen Kryptoanalytiker Alan Turing ersonnene und von seinem Landsmann Gordon Welchman verbesserte elektromechanische „Knackmaschine“, die sogenannte Turing-Welchman-Bombe.

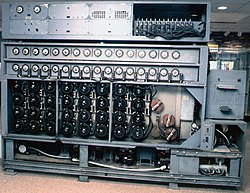

Mit Inbetriebnahme der Enigma-M4 im Februar 1942 gab es jedoch eine für die Alliierten schmerzliche Unterbrechung (Black-out), denn der U‑Boot-Funkverkehr konnte nun plötzlich nicht mehr „mitgelesen“ werden. Im Auftrag von Op‑20‑G der US Navy (Office of Chief Of Naval Operations, 20th Division of the Office of Naval Communications, G Section/Communications Security) sollte deshalb umgehend, basierend auf dem britischen Konzept, eine amerikanische Hochgeschwindigkeits-Versionen der Bombe entwickelt werden. Federführend damit beauftragt wurde der damals 34-jährige Joseph Desch (1907–1987),[5] ein in Dayton geborener und aufgewachsener Ingenieur. Ziel war eine Geschwindigkeitssteigerung um den Faktor 26 gegenüber dem britischen Vorbild. Tatsächlich erreichte man etwas mehr als den Faktor fünfzehn. Die realisierte Bombe (Bilder) hatte die Abmessungen eines großen Wohnzimmerschranks; sie war mehr als zwei Meter hoch, drei Meter breit und fast einen Meter tief, bei einem Gewicht von rund 2500 Kilogramm.[6]

Ab April 1943 wurden mehr als 120 Stück dieser Desch-Bombes produziert und die Entzifferung des U‑Boot-Funkverkehrs gelang erneut[7][8], nachdem die Briten wichtige Geheimunterlagen erbeutet hatten. Zu dieser Zeit umfasste die von Desch geleitete Gruppe des NCML etwa dreißig zivile Mitarbeiter. Dazu kamen hunderte WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), also Frauen, die zum freiwilligen Notdienst bei der US Navy angenommen worden waren. Sie waren etwa einen Kilometer südlich von Building 26 im sogenannten Sugar Camp (deutsch „Zuckerlager“) untergebracht, einem in einem Ahornwald idyllisch gelegenen etwa zwölf Hektar großen Wohnkomplex (39° 44′ N, 84° 11′ W) mit sechzig komfortabel eingerichteten Blockhütten (englisch cabins).[9] Ferner arbeiteten weitere etwa Tausend zivile NCR-Angestellte an der Fertigung der Bombes.[10] Hunderte von männlichen Marinesoldaten bewachten die Einrichtung und ihre Geheimnisse und sorgten für die Sicherheit des Personals.

Unmittelbare Folge der amerikanischen Entzifferungen war, beginnend mit U 463 am 16. Mai 1943, einem U‑Tanker vom Typ XIV („Milchkuh“), bis U 220 am 28. November 1943, einem zur Versorgung eingesetzten Minenleger vom Typ XB,[11] die Versenkung von elf der achtzehn deutschen Versorgungs-U‑Boote innerhalb weniger Monate im Jahr 1943.[12] Dies führte zu einer Schwächung aller Atlantik-U‑Boote, die nun nicht mehr auf See versorgt werden konnten, sondern dazu die lange und gefährliche Heimreise durch die Biskaya zu den U‑Boot-Stützpunkten an der französischen Westküste antreten mussten.

Späte Würdigung

Im Oktober 2001, beim zweiten Treffen der Veteranen des U.S. Naval Computing Machine Laboratory in Dayton, wurden die ehemaligen Mitarbeiter des Building 26 für ihre herausragenden elektrotechnischen Leistungen, die „…den Verlauf des Zweiten Weltkriegs maßgeblich beeinflusst haben“ (englisch …significantly influenced the course of World War II), mit dem renommierten IEEE-Milestone ausgezeichnet.[13][14]

Gegen den Protest vieler Angehöriger und Anwohner wurde das altehrwürdige Gebäude 26 schließlich im Januar 2008 abgerissen.[15][16]

Literatur

- Jim DeBrosse und Colin Burke: The Secret in Building 26 – The Untold Story of How America Broke the Final U‑boat Enigma Code. Random House, New York 2005, ISBN 0-375-50807-4.

- Chris Christensen: US Navy Cryptologic Mathematicians during World War II. Cryptologia, 35:3, S. 267–276, 2011. doi:10.1080/01611194.2011.558609.

- Chris Christensen: The National Cash Register Company Additive Recovery Machine. Cryptologia, 38:2, S. 152–177, 2014. doi:10.1080/01611194.2013.797050.

- Magnus Ekhall und Fredrik Hallenberg: US Navy Cryptanalytic Bombe – A Theory of Operation and Computer Simulation. HistoCrypt 2018, S. 103–108, PDF; 330 kB.

- David Kahn: Seizing the Enigma – The Race to Break the German U‑Boat Codes, 1939–1943. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, USA, 2012. ISBN 978-1-59114-807-4.

Weblinks

- Gruppenfoto (ca. 1945) von Mitarbeitern des NCML. In der vorderen Reihe links steht Joe Desch. Abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- Foto (2007) Deborah Anderson, Tochter von Joe Desch, vor Building 26, das kurz darauf abgerissen wurde. Abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- Dayton Codebreakers Homepage (englisch), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- US Naval Computing Machine Laboratory, 1942–1945 (englisch), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ John A. N. Lee, Colin Burke, Deborah Anderson: The US Bombes, NCR, Joseph Desch, and 600 WAVES – The first Reunion of the US Naval Computing Machine Laboratory. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 2000. S. 35. PDF; 0,5 MB, abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- ↑ Impact Of Bombe On The War Effort ( vom 17. September 2011 im Internet Archive), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- ↑ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma – The battle for the code. Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, S. 136. ISBN 0-304-36662-5.

- ↑ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma – The battle for the code. Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, S. 149 ff. ISBN 0-304-36662-5.

- ↑ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore: Enigma – The battle for the code. Cassell Military Paperbacks, London 2004, S. 311. ISBN 0-304-36662-5.

- ↑ David Kahn: Seizing the Enigma – The Race to Break the German U‑Boat Codes, 1939–1943. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, USA, 2012, S. 280. ISBN 978-1-59114-807-4

- ↑ Jennifer Wilcox: Solving the Enigma – History of the Cryptanalytic Bombe. Center for Cryptologic History, NSA, Fort Meade (USA) 2001, S. 52.PDF; 0,6 MB ( vom 15. Januar 2009 im Internet Archive)

- ↑ John A. N. Lee, Colin Burke, Deborah Anderson: The US Bombes, NCR, Joseph Desch, and 600 WAVES – The first Reunion of the US Naval Computing Machine Laboratory. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 2000, S. 27 ff.

- ↑ Keeping the Secret – The Waves & NCR Sugar Camp / Building Twenty-Six (englisch), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- ↑ The Story in Brief (englisch), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- ↑ Erich Gröner: Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe 1815–1945;- Band 3: U‑Boote, Hilfskreuzer, Minenschiffe, Netzleger, Sperrbrecher. Bernard & Graefe, Koblenz 1985, ISBN 3-7637-4802-4, S. 118f

- ↑ Laut Hans Herlin: Verdammter Atlantik – Schicksale deutscher U‑Boot-Fahrer. Heyne, München 1985, S. 282–288, ISBN 3-453-00173-7, gingen von Mai bis Oktober 1943 die folgenden Boote vom Typ XB (4 von 8) beziehungsweise Typ XIV (7 von 10) verloren:

01) am 15. Mai; jedoch lt. Wikipedia am 16. Mai U 463 (Typ XIV),

02) am 12. Juni U 118 (Typ XB),

03) am 24. Juni U 119 (Typ XB),

04) am 13. Juli U 487 (Typ XIV),

05) am 24. Juli U 459 (Typ XIV),

06) am 30. Juli U 461 (Typ XIV),

07) am 30. Juli U 462 (Typ XIV),

08) am 04. Aug. U 489 (Typ XIV),

09) am 07. Aug. U 117 (Typ XB),

10) am 04. Okt. U 460 (Typ XIV),

11) am 12. Okt.; jedoch lt. Wikipedia am 28. Nov. U 220 (Typ XB).

In Summe also 11 der 18 zur Versorgung eingesetzten U‑Boote. - ↑ Milestone in Engineering IEEE-Milestone als Auszeichnung für die Mitarbeiter des Building 26 (englisch), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- ↑ Milestones: List of IEEE Milestones (englisch), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- ↑ War Over a Building That Helped Win One The New York Times vom 1. April 2007 (englisch), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

- ↑ Demolition of Building 26 (englisch), abgerufen am 16. Mai 2018.

Koordinaten: 39° 44′ 22″ N, 84° 11′ 29″ W

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

U-110 was captured by HM Ships Bulldog, Broadway and Arbretia

Die amerikanische Hochgeschwindigkeits-Variante der Turing-Bombe war speziell gegen die Vierwalzen-Enigma gerichtet

Autor/Urheber: J Brew, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 2.0

A US Navy WAVE sets the Bombe rotors prior to a run

The US NAvy cryptanalytic Bombes had only one purpose: Determine the rotor settings used on the German cipher machine ENIGMA. Originally designed by <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Desch">Joseph Desch</a> with the National Cash Register Company in Dayton, Ohio, the Bombes worked primarily against the German Navy's four-rotor ENIGMAs. Without the proper rotor settings, the messages were virtually unbreakable. The Bombes took only twenty minutes to complete a run, testing the 456,976 possible rotor settings with one wheel order. Different Bombes tried different wheel orders, and one of them would have the final correct settings. When the various U-boat settings were found, the Bombe could be switched over to work on German Army and Air Force three-rotor messages. Source: National Cryptologic Museum

Comment on the above The four rotor system had 26^4 or 456,976 settings whilst the theree rotor system had 26^3 or 17,756 settings. It looks like the problem scale in a linear way as it took 50 seconds to check 17,756 setting (~350 per second) while the four rotor solution in 20 minutes is ~ 380 settings per second.

I also think the designer <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Desch">Joseph Desch</a> sounds like a remarkable engineer that I never heard of before.

<a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombe">Bombe</a> on Wikipedia Once the British had given the Americans the details about the bombe and its use, the US had the National Cash Register Company manufacture a great many additional bombes, which the US then used to assist in the code-breaking. These ran much faster than the British version, so fast that unlike the British model, which would freeze immediately (and ring a bell) when a possible solution was detected, the NCR model, upon detecting a possible solution, had to "remember" that setting and then reverse its rotors to back up to it (meanwhile the bell rang).

Source of following material : National Cryptologic Museum

Diagonal Board is the heart of the Bombe unit. Electrically, it has 26 rows and 26 columns of points, each with a diagonal wire connection. These wires connect each letter in a column with the same position in each row. A letter cannot plug into itself; these are known as "self-steckers." The resulting pattern is a series of diagonal lines. The purpose of the diagonal board is to eliminate the complications caused by the Enigma's plugboard. Given specific rotor settings, only certain plugboard settings can result in the proper encrypted letter. The diagonal board disproved hundreds of rotor settings, allowing for only a few possibly correct settings to result in a "strike".

Amplifier Chassis had two purposes, first to detect a hit and second to determine if it was useful. It provided the tie-in from the diagonal board, the locator, and the printer circuits.

Thyratron Chassis was the machine's memory. Since the wheels spun at such a high speed, they could not immediately stop rotating when a correct hit was detected. The Thyratron remembered where the correct hit was located and indicated when the Bombe has rewound to that position. It also told the machine when it had completed a run and gave the final stop signal.

Switch Banks tell the Bombe what plain to cipher letters to search for. Using menus sent to the Bombe deck by cryptanalysts, WAVES set each dial using special wrenches. 00 equates to the letter A and 25 to the letter Z. The dials work together in groups of two. One dial is set to the plain test letter and the other to its corresponding cipher letter as determined by cryptanalysts. There are sixteen sets of switch banks, however, only fourteen were required to complete a run. As the machine worked through the rotor settings, a correct hit was possible if the electrical path in all fourteen switch banks corresponded to each of their assigned plaintext/cipher combinations.

Wheel Banks represent the four rotors used on the German U-boat Enigma. Each column interconnects the four rotors, or commutators, in that column. The top commutator represented the fourth, or slowest, rotor on the Enigma, while the bottom wheel represented the rightmost, or fastest, rotor. The WAVES set the rotors according to the menu developed by the cryptanalysts. The first were set to 00, and each set after that corresponded to the plain/cipher link with the crib (the assumed plain test corresponding to the cipher text.) Usually this meant that each wheel bank stepped up one place from the one on its left. When the machine ran, each bottom rotor stepped forward, and the machine electrically checked to see if the assigned conditions were met. If not, as was usually the case, each bottom wheels moved one more place forward. However, the bottom commutator moved at 850 rpm, so it only took twenty minutes to complete a run of all 456,976 positions.

Printer automatically printed the information of a possible hit. When the Bombe determined that all the possible conditions had been met. it printed wheel order, rotor settings and plugboard connections.

Motor Control Chassis controlled both forward and reverse motors. The Bombe was an electromechanical machine and required a number of gauges for monitoring. It also needed a Braking Assembly to slow the forward motion when a hit was detected and to bring the machine to a full stop when a run was completed.