Schokalskibucht

| Schokalskibucht | ||

|---|---|---|

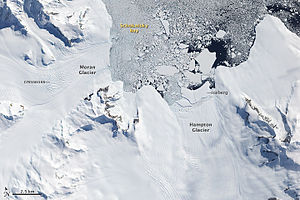

Satellitenaufnahme der Schokalskibucht (2009) | ||

| Gewässer | George-VI-Sund | |

| Landmasse | Alexander-I.-Insel, Westantarktika | |

| Geographische Lage | 69° S, 70° W | |

| ||

| Breite | 10 km | |

| Tiefe | 14,5 km | |

| Zuflüsse | Hampton-Gletscher, Moran-Gletscher | |

Die Schokalskibucht ist eine Bucht, die sich über 10 km Länge zwischen dem Mount Calais und dem Kap Brown an der Ostküste der antarktischen Alexander-I.-Insel erstreckt. Vom Hampton-Gletscher kalben enorme Eismassen über einen steilen und stark zerklüfteten Gletscherbruch in die Bucht, weshalb sie nicht als sicherer Ankerplatz und der Gletscher gleichsam nicht als Aufstiegsroute in das Innere der Insel in Frage kommen.

Erstmals gesichtet und grob kartiert wurde die Bucht 1909 bei der Fünften Französischen Antarktisexpedition (1908–1910) unter der Leitung Jean-Baptiste Charcots. Dieser hielt die Bucht irrtümlich für eine Meerenge und benannte sie nach dem russischen Ozeanographen Juli Michailowitsch Schokalski (1856–1940) entsprechend als Detroit Schokalsky. Bei der British Grahamland Expedition (1934–1937) unter der Leitung des australischen Polarforschers John Rymill konnte Charcots Entdeckung nicht identifiziert werden. Erst Vermessungsarbeiten des Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey im Jahr 1948 offenbarten, dass es sich dabei um die hier beschriebene Bucht handeln musste.

Weblinks

- Schokalsky Bay. (ZIP; 1,76 MB) In: Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey (englisch). (englisch)

- Schokalsky Bay auf geographic.org (englisch)

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

(c) Karte: NordNordWest, Lizenz: Creative Commons by-sa-3.0 de

Positionskarte der Antarktischen Halbinsel

Few places on Earth have warmed more rapidly in recent decades than the Antarctic Peninsula, a narrow, mountainous spine of land that juts out from the continent into the Southern Ocean. More than 400 glaciers—often steep and heavily traced with crevasses—flow out of nearly every nook and cranny of the rugged peninsula, and the regional warming has caused the edges of many of these glaciers to retreat and their flow toward the ocean to accelerate. Faster flow of tidewater glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula is adding directly to sea level rise.

This image of the northern tip of Alexander Island, near the western base of the Antarctic Peninsula, illustrates one of the processes through which glaciers can contribute to sea level rise: iceberg production. In this image, several large icebergs have calved from Hampton Glacier. Near the glacier, the bergs appear to be partially held in place by a mélange of ice that may include tiny iceberg fragments and frozen sea water. Farther out in Shokalsky Bay, the icebergs are floating more freely. Eventually, the bergs will drift northward to warmer waters, where they will melt.

All glaciers that end in the ocean (called tidewater glaciers) periodically calve icebergs. When iceberg production is matched by snowfall accumulation on the glacier, the glacier is not contributing to sea level rise: all the water it adds to the ocean eventually returns to the glacier as snow. But if iceberg production (or a combination of iceberg production and melting) outpaces snowfall accumulation, then the glacier is contributing to sea level rise.

Measuring the thickness and flow rates of glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula is one of the objectives of an upcoming NASA aircraft campaign called Operation Ice Bridge. Beginning on October 12, 2009, and continuing for 6 weeks, NASA’s DC-8 research airplane and the Ice Bridge team scientists will make a series of flights from a base in southern Chile to collect observations over West Antarctica, the Antarctic Peninsula, and coastal areas where sea ice is prevalent. Each round-trip flight lasts about eleven hours, two-thirds of that time devoted to getting to and from Antarctica.

References

Pritchard, H.D., and Vaughan, D.G. (2007). Widespread acceleration of tidewater glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula. Journal of Geophysical Research, 112, F03S29.