Prochlorococcus marinus

| Prochlorococcus marinus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

SEM-Aufnahme von Prochlorococcus marinus (koloriert) | ||||||||||||

| Systematik | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Wissenschaftlicher Name der Gattung | ||||||||||||

| Prochlorococcus | ||||||||||||

| S.W. Chisholm, S.L. Frankel, R. Goericke, R.J. Olson, B. Palenik, J.B. Waterbury, L. West-Johnsrud & E.R. Zettler | ||||||||||||

| Wissenschaftlicher Name der Art | ||||||||||||

| Prochlorococcus marinus | ||||||||||||

| S.W. Chisholm, R.J. Olson, E.R. Zettler, J.B. Waterbury, R. Goericke & N. Welschmeyer |

Prochlorococcus marinus ist die einzige bekannte und wissenschaftlich beschriebene Art der Gattung Prochlorococcus. Es ist ein vorwiegend marin verbreitetes, Photosynthese betreibendes, einzelliges Cyanobakterium. Prochlorococcus gehört zu den kleinsten bekannten photoautotrophen Organismen und damit zum sog. Picoplankton. Aufgrund seiner hohen Konzentration in weiten Bereichen der Ozeane ist er nach aktuellem Forschungsstand das Lebewesen mit der höchsten Individuenanzahl und zugleich das am weitesten verbreitete Lebewesen der Erde und spielt bei der Primärproduktion organischer Stoffe eine besonders große Rolle.[1][2][3]

Merkmale

Die Zellen sind mit 0,5 bis 0,8 µm Durchmesser – verglichen mit anderen Cyanobakterien – klein. Sie gehören damit zu den kleinsten bekannten Photosynthese betreibenden Organismen und werden dem Picoplankton zugeordnet.[4] Die Licht absorbierenden Pigmente (Photosynthesepigmente) von Prochlorococcus bestehen hauptsächlich aus Chlorophyll a2 (Chl a2) und b2 (Chl b2), dies sind Divinyl-Derivate der in Pflanzen vorkommenden Chlorophylle a und b. Mono-Vinyl-Chlorophylle kommen jedoch nicht vor.[1]

Das Genom von Prochlorococcus marinus wurde vollständig sequenziert. Die Analyse der Genomsequenzen von 12 Prochlorococcus-Stämmen zeigt, dass 1.100 Gene allen Stämmen gemeinsam sind und die durchschnittliche Genomgröße bei etwa 2.000 Genen liegt.[2] Im Gegensatz dazu haben eukaryotische Algen über 10.000 Gene.[5]

Verbreitung

Prochlorococcus ist zahlenmäßig nach aktuellem Kenntnisstand der häufigste und am weitesten verbreitete Organismus der Erde.[4] Er kommt hauptsächlich in den Ozeanen zwischen den Breitengraden 40° N und 40° S in den oberen 100 bis 150 m vor, und zwar vor allem in nährstoffarmen (oligotrophen) Bereichen mit einer Wassertemperatur von mindestens 10 °C. Dabei erreicht er Konzentrationen von 1·105 bis 3·105 je Milliliter und 1011 bis 1014 je Quadratmeter und stellt einen beträchtlichen Anteil des Bakterioplanktons aller Ozeane dar.[1]

Lebensweise und Ökologie

Als photoautotropher Organismus steht Prochlorococcus am Beginn der Nahrungskette und ist für einen wesentlichen Teil der marinen Primärproduktion verantwortlich. Die Zellen teilen sich unter natürlichen Bedingungen im Mittel einmal täglich. Das bedeutet, dass jeden Tag 50 Prozent der gesamten Prochlorococcus-Biomasse in die marinen Nahrungsnetze eintreten.

Prochlorococcus besiedelt hauptsächlich zwei ökologische Nischen: Neben oberflächennah lebenden Populationen findet man Photosynthese betreibende Zellen auch bis in Tiefen von über 150 Meter. Hier stehen weniger als 1 Prozent der oberflächennahen Lichtintensität zur Verfügung und das Elektromagnetische Spektrum des Lichtes enthält nur noch den Blauanteil. Diese an Schwachlicht adaptierten Zellen verfügen über Antennenpigmente, die auch blaues Licht geringer Intensität absorbieren können und ein Überleben ermöglichen. Entsprechend werden die Bakterien in zwei Gruppen eingeteilt: Mitglieder der low light (LL)-Gruppe besitzen ein höheres Verhältnis von Chlorophyll b2 : a2 als Mitglieder der high light (HL)-Gruppe. Die Gruppen unterscheiden sich außerdem in ihren Stickstoff- und Phosphatanforderungen sowie in ihrer Sensibilität gegenüber Kupferverbindungen und Viren. Hochlichtadaptierte Stämme bewohnen Tiefen zwischen 25 und 100 m, während niedriglichtadaptierte Stämme Gewässer zwischen 80 und 200 m bewohnen. Diese Ökotypen können anhand der Sequenz ihres ribosomalen RNA-Gens unterschieden werden.[6][7]

Forschungsgeschichte

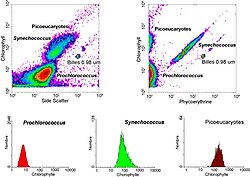

Die frühesten Hinweise auf sehr kleine Chlorophyll-b-haltige Cyanobakterien im Ozean stammen aus den Jahren 1979[8] und 1983.[9] Die Gattung Prochlorococcus wurde 1986 von Sallie W. (Penny) Chisholm (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), Robert J. Olson (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) und weiteren Mitarbeitern in der Sargassosee mittels Durchflusszytometrie entdeckt.[10] Für die Entdeckung wurde Chisholm 2019 mit dem Crafoord-Preis ausgezeichnet.[11] Die erste Kultur von Prochlorococcus wurde 1988 in der Sargassosee isoliert (Stamm SS120) und kurz darauf wurde ein weiterer Stamm aus dem Mittelmeer gewonnen (Stamm MED). Der Name Prochlorococcus wurde gewählt, weil man ursprünglich annahm, dass Prochlorococcus mit Prochloron und anderen Chlorophyll b enthaltenden Bakterien, sodass auch die hier verwendete Systematik nach NCBI die Gattung in die Prochlorophyten (Prochlorales) einreihte.[12]

Systematik

Inzwischen ist aber bekannt, dass die Prochlorophyten (wiss. Prochlorophyta) mehrere separate phylogenetische Zweige innerhalb der Cyanobakterien bilden. Anhand der rRNA-Sequenzen erkannte man, dass es sich bei Prochlorococcus um eine eigenständige Gruppe unter den Cyanobakterien handelt, die zwar die Divinyl-Derivate von Chlorophyll a und b, aber keine Mono-Vinyl-Chlorophylle enthalten. Prochlorococcus ist der einzige bekannte sauerstoffhaltige phototrophe Wildtyp, der kein Chl a als Hauptphotosynthesepigment enthält, und ist der einzige bekannte Prokaryote mit α-Carotin.[13]

Neuere Phylogenien (Stand 2021) fassen die Gattung Prochlorococcus und die marinen Synechococcus in einer Klade „mariner Picocyanobacteria“ (auch „marine SynPro-Gruppe“ genannt) zusammen, deren letzter gemeinsamer Ahn (LGA oder MRCA) vor etwa 414 (340 bis 419) Millionen Jahren gelebt hat. Die Auseinanderentwicklung (Divergenz) dieser Gruppe und der Gattungen Cyanobium, Aphanothece, sowie anderer verwandter Synechococcus-Vertreter wird im späten Ediacarium (vor 571 Millionen Jahren) angenommen.[14]

Viren

Es gibt eine Reihe bekannter Viren, die Prochlorococcus infizieren, und daher nicht-taxonomisch als Cyanophagen klassifiziert werden. Die vom International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) bestätigten Spezies (Stand Januar 2022) gehören den Familien Autographiviridae (Podoviren) und Kyanoviridae (Myoviren) sowie der Gattung Eurybiavirus (Myoviren) an – alle in der Klasse Caudoviricetes:[15][16]

- Familie Autographiviridae (Podoviren)

- Gattung Banchanvirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus SS120-1 (wissenschaftlich Banchanvirus SS1201)

- Gattung Cheungvirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus NATL1A7 (wiss. Cheungvirus NATL1A7)

- Gattung Lingvirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PGSP1 (wiss. Lingvirus PGSP1)

- Gattung Tangaroavirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus 951510a (wiss. Tangaroavirus tv951510a)

- Prochlorococcus virus NATL2A133 (wiss. Tangaroavirus NATL2A133)

- Prochlorococcus virus PSSP10 (wiss. Tangaroavirus PSSP10)

- Gattung Tiamatvirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PSSP7 (wiss. Tiamatvirus PSSP7)

- Gattung Tritonvirus

- Prochlorococcus virus PSSP3 (wiss. Tritonvirus PSSP3)

- Familie Kyanoviridae (Myoviren)

- Gattung Brizovirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus Syn33 (wiss. Brizovirus syn33)

- Gattung Libanvirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PTIM40 (wiss. Libanvirus ptim40)

- Gattung Palaemonvirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PSSM7 (wiss. Palaemonvirus pssm7)

- Gattung Ronodorvirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PSSM3 (wiss. Ronodorvirus pssm3)

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PSSM4 (wiss. Ronodorvirus pssm4)

- Gattung Salacisavirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PSSM2 (wiss. Salacisavirus pssm2)

- Gattung Vellamovirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus Syn1 (wiss. Vellamovirus syn1)

- Myoviren ohne Familienzuordnung

- Gattung Eurybiavirus

- Prochlorococcus-Virus MED4-213 (wiss. Eurybiavirus MED4213)

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PHM1 (wiss. Eurybiavirus PHM1)

- Prochlorococcus-Virus PHM2 (wiss. Eurybiavirus PHM2)

Belege

- ↑ a b c F. Partensky, W. R. Hess, D. Vaulot: Prochlorococcus, a marine photosynthetic prokaryote of global significance, in: Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, Band 63, Nr. 1, 1999, S. 106–127.

- ↑ a b C. Munn: Marine Microbiology: ecology and applications Second Ed. Garland Science, 2011.

- ↑ Life at the Edge of Sight — Scott Chimileski, Roberto Kolter | Harvard University Press. In: www.hup.harvard.edu. (englisch).

- ↑ a b Thomas M. Smith, Robert L. Smith: Ökologie. Pearson Studium, München 2009; S. 447. ISBN 978-3-8273-7313-7.

- ↑ G. C. Kettler, A. C. Martiny, K. Huang et al.: Patterns and Implications of Gene Gain and Loss in the Evolution of Prochlorococcus. In: PLOS Genetics. 3. Jahrgang, Nr. 12, Dezember 2007, S. e231, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030231, PMID 18159947, PMC 2151091 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ N. J. West, D. J. Scanlan: Niche-partitioning of Prochlorococcus in a stratified water column in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean. In: Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 65. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 1999, S. 2585–2591, doi:10.1128/AEM.65.6.2585-2591.1999, PMID 10347047, PMC 91382 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ A. C. Martiny, A. Tai, D. Veneziano, F. Primeau, S. Chisholm: Taxonomic resolution, ecotypes and biogeography of Prochlorococcus. In: Environmental Microbiology. 11. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, 1. April 2009, S. 823–832, doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01803.x, PMID 19021692.

- ↑ Paul W. Johnson, John McN. Sieburth: Chroococcoid cyanobacteria in the sea: a ubiquitous and diverse phototrophic biomass. In: Limnology and Oceanography. 24. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, September 1979, S. 928–935, doi:10.4319/lo.1979.24.5.0928, bibcode:1979LimOc..24..928J.

- ↑ Winfried W. Gieskes, Gijsbert W. Kraay: Unknown chlorophyll a derivatives in the North Sea and the tropical Atlantic Ocean revealed by HPLC analysis. In: Limnology and Oceanography. 28. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, Juli 1983, S. 757–766, doi:10.4319/lo.1983.28.4.0757, bibcode:1983LimOc..28..757G.

- ↑ Sallie W. Chisholm, Robert J. Olson, Erik R. Zettler, Ralf Goericke, John B. Waterbury, Nicholas A. Welschmeyer: A novel free-living prochlorophyte occurs at high cell concentrations in the oceanic euphotic zone. In: Nature. 334. Jahrgang, Nr. 6180, 1. Juli 1988, S. 340–343, doi:10.1038/334340a0, bibcode:1988Natur.334..340C.

- ↑ The Crafoord Prize in Biosciences 2019, The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- ↑ Sallie W. Chisholm, S. L. Frankel, R. Goericke, R. J. Olson, B. Palenik, J. B. Waterbury, L. West-Johnsrud & E. R. Zettler: Prochlorococcus marinus nov. gen. nov. sp.: an oxyphototrophic marine prokaryote containing divinyl chlorophyll a and b. In: Archives of Microbiology. 157. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, 1992, S. 297–300, doi:10.1007/BF00245165.

- ↑ R. Goericke, D. Repeta: The pigments of Prochlorococcus marinus: the presence of divinyl chlorophyll a and b in a marine prokaryote. In: Limnology and Oceanography. 37. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, 1992, S. 425–433, doi:10.4319/lo.1992.37.2.0425, bibcode:1992LimOc..37..425R.

- ↑ G. P. Fournier, K. R. Moore, L. T. Rangel, J. G. Payette, L. Momper, T. Bosak: The Archean origin of oxygenic photosynthesis and extant cyanobacterial lineages, Band 288, Nr. 1959, 29. September 2021, doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.0675, PMID 34583585. Siehe insbes. Fig. 2

- ↑ ICTV: ICTV Master Species List 2020.v1, Email ratification March 2021 (MSL #36)

- ↑ NCBI: Suche: Prochlorococcus Viren (tendenziell ICTV-bestätigt), und Suche: Prochlorococcus Phagen (tendenziell ICTV-unbestätigt).

Weblinks

- Lisa Campbell H. A. Nolla Daniel Vaulot: The importance of Prochlorococcus to community structure in the central North Pacific Ocean. In: Limnology and Oceanography. 39. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, Juni 1994, S. 954–961, doi:10.4319/lo.1994.39.4.0954, bibcode:1994LimOc..39..954C (englisch).

- Jagroop Pandhal, Phillip C. Wright, Catherine A. Biggs: A quantitative proteomic analysis of light adaptation in a globally significant marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus MED4. In: Journal of Proteome Research. 6. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, 14. Februar 2007, S. 996–1005, doi:10.1021/pr060460c, PMID 17298086 (englisch).

- Melissa Garren: The sea we've hardly seen. In: TEDx Monterey. 2012, S. 52 f. (englisch, ted.com).

- Steve Nadis: The Cells That Rule the Seas. Scientific American Magazine, Dezember 2003, S. 52f.

- M. D. Guiry: Prochlorococcus S. W. Chisholm, S. L. Frankel, R. Goericke, R. J. Olson, B. Palenik, J. B. Waterbury, L. West-Johnsrud & E. R. Zettler 1992: 299. In: AlgaeBase. (englisch).

- The Most Important Microbe You've Never Heard Of: NPR Story on Prochlorococcus

- NCBI: Genome Information for Prochlorococcus marinus

- Connor R. Love, Eleanor C. Arrington, Kelsey M. Gosselin, Christopher M. Reddy, Benjamin A. S. Van Mooy, Robert K. Nelson, David L. Valentine: Microbial production and consumption of hydrocarbons in the global ocean. In: Nature Microbiology, Band 6, 1. Februar 2021, S. 489–498; doi:10.1038/s41564-020-00859-8. Dazu:

- Tessa Koumoundouros: Scientists Discover An Immense, Unknown Hydrocarbon Cycle Hiding in The Oceans. Auf: sciencealert vom 12. August 2022.

- Giovanna Capovilla, Rogier Braakman, Sallie W. Chisholm et al.: Chitin utilization by marine picocyanobacteria and the evolution of a planktonic lifestyle. In: PNAS, Band 120. Nr. 20, 9. Mai 2023, e2213271120; doi:10.1073/pnas.2213271120. Dazu:

- Anna Manz: Cyanobakterien als Seefahrer – Phytoplankton-Vorfahren besiedelten das offene Meer mittels Chitin-Flößen. Auf: scinexx.de vom 17. Mai 2023.

- Jennifer Chu: Tiny Ocean Conquerors: How Ancestors of Prochlorococcus Microbes Mastered the Seas on Exoskeleton Rafts. Auf: SciTechDaily vom 15. Mai 2023.

- Rui-Qian Zhou, Yong-Liang Jjang, Haofu Li, Pu Hou, Wen-Wen Kong, Jia-Xin Deng, Yuxing Chen, Cong-Zhao Zhou, Qinglu Zeng: Structure and assembly of the α-carboxysome in the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus. In: Nature Plants, Band 10, 8. April 2024, S. 661–672; doi:10.1038/s41477-024-01660-9 (englisch). Gegenstand lt. Studie: Prochlorococcus MED4. Dazu:

- NCBI Taxonomy Browser: Prochlorococcus marinus subsp. pastoris str. CCMP1986 (strain, heterotypic synonym: Prochlorococcus sp. MED4).

- Key Carboxysome Discovery Brings Scientists a Giant Step Closer to Supercharged Photosynthesis. Auf: SciTechDaily vom 22. Mai 2024.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Autor/Urheber: Luke Thompson from Chisholm Lab and Nikki Watson from Whitehead, MIT, Lizenz: CC0

TEM image of Prochlorococcus marinus with overlay green coloring. A globally significant marine cyanobacterium.

Autor/Urheber: Chisholm Lab, Lizenz: CC0

Taken by Anne Thompson, Chisholm Lab, MIT. SEM of MIT9215 Pseudo-colored. The Chisholm Lab gives you permission to use this image. This is the highest resolution image available.

Autor/Urheber: Kazuyoshi Murata, Qinfen Zhang, Jesús Gerardo Galaz-Montoya, Caroline Fu, Maureen L. Coleman, Marcia S. Osburne, Michael F. Schmid, Matthew B. Sullivan, Sallie W. Chisholm & Wah Chiu, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Adsorption of P-SSP7 phage to Prochlorococcus MED4 visualized by cryo-ET.

(a) Slice (~20 nm) through a reconstructed tomogram of P-SSP7 phage incubated with MED4, imaged at ~86 min post-infection, and (b) corresponding annotation highlighting the cell wall in orange, the plasma membrane in light yellow, the thylakoid membrane in green, carboxysomes in cyan, the polyphosphate body in blue, adsorbed phages on the sides or top of the cell in red, and cytoplasmic granules (probably mostly ribosomes) in light purple. FC and EC show full-DNA capsid phage and empty capsid phage, respectively. Scale bar is 200 nm.

Autor/Urheber: Daniel Vaulot, CNRS, Station Biologique de Roscoff, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 2.5

Analysis of a marine sample of photosyntetic picoplankton by flow cytometry showing three different populations (Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus and picoeukaryotes).