Plasmasphäre

Die Plasmasphäre ist der innere, zu einem Torus geschlossene Teil der irdischen Magnetosphäre und von einem relativ kühlen Plasma, T = 6000 bis 35.000 K, aus Elektronen und hauptsächlich Protonen (H+) erfüllt.

Die äußere Grenze der Plasmasphäre ist die sogenannte Plasmapause, die sich durch einen rapiden Abfall der Plasmadichte auszeichnet. In Richtung Sonne liegt die Plasmapause in einer Höhe von etwa vier Erdradien, auf der Nachtseite bei etwa 6 bis 7 Erdradien. Dort geht Plasma in Richtung Magnetschweif verloren. Diese Verluste werden ersetzt aus der Ionosphäre, deren Fortsetzung die Plasmasphäre darstellt. Dies geschieht parallel zu den Feldlinien, ausgehend von hohen Breitengraden.

Der Abfall der Elektronendichte jenseits der F-Schicht der Ionosphäre ist exponentiell, zunächst mit einer Skalenhöhe, die der Abnahme der Konzentration ionisierten, atomaren Sauerstoffs (O+) entspricht, dann der langsameren Abnahme von H+ folgend. Die Übergangshöhe bei etwa 1000 km wird manchmal etwas willkürlich als Obergrenze der Ionosphäre definiert.[1]

Die Plasmasphäre, genauer: der Knick der Elektronendichte an der Plasmapause, wurde 1963 von Don Carpenter während der Analyse von Whistlern entdeckt.[2]

Ursprünglich wurde die Plasmasphäre als wohlgeformtes, kaltes Plasma angesehen, dessen Teilchenbewegung vollständig vom Erdmagnetfeld bestimmt wird und daher mit der Erde korotiert. Dahingegen haben neuere Satellitenbeobachtungen gezeigt, dass sich Dichteunregelmäßigkeiten wie Wolken oder Fehlstellen bilden können. Des Weiteren wurde gezeigt, dass die Plasmasphäre nicht beständig mit der Erde korotiert.

Siehe auch

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Stefan Heise: Rekonstruktion dreidimensionaler Elektronendichteverteilungen basierend auf CHAMP-GPS-Messungen. FU Berlin, 2002, Kapitel 2: Die Ionosphäre und Plasmasphäre der Erde, urn:nbn:de:kobv:188-2002002731 (fu-berlin.de [PDF] Dissertation).

- ↑ J. Lemaire, K. I. Gringauz, David L. Carpenter, V. Bassolo: The earth's plasmasphere. Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-67555-0 (englisch).

Literatur

- B. R. Sandel, et al.: Extreme ultraviolet imager observations of the structure and dynamics of the plasmasphere. In: Space Sci. Rev. Band 109, 2003, S. 25 (englisch).

- D. L. Carpenter: Whistler evidence of a 'knee' in the magnetospheric ionization density profile. In: J. Geophys. Res. Band 68, 1963, S. 1675–1682 (englisch).

- A. Nishida: Formation of plasmapause, or magnetospheric plasma knee, by combined action of magnetospheric convections and plasma escape from the tail. In: J. Geophys. Res. Band 71, 1966, S. 5669 (englisch).

Weblinks

- IMAGE Extreme Ultraviolet Imager

- EUV Bilder der Plasmasphäre

- NASA Webseite

- University of Michigan: Beschreibung

- University of Alabama in Huntsville: Plasmasphere Research (Memento vom 9. Juni 2010 im Internet Archive)

- Southwest Research Institute: Beschreibung

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

This is Image 4 of the NASA article.

These images are taken from a computer animation illustrating the Earth's space storm shield in action. The solar wind, a thin, high-velocity electrified gas, or plasma, blows constantly from the Sun at an average speed of 250 miles per second (400 kilometers/sec). It is represented in Image 1 as a stream of yellow particles flowing from the Sun. The solar wind impacts the Earth's magnetic field, represented by the blue lines in Image 2. As the solar wind flows past the Earth's magnetic field, it generates enormous electric currents that heat Earth's space storm shield -- a layer in the Earth's electrically charged outer atmosphere (ionosphere) -- causing the shield to eject electrically charged oxygen atoms (oxygen ions) into space. The expelled oxygen ions are represented by the green particle streams in Image 3. The ejected oxygen ions gain tremendous speed as they leave the atmosphere, become trapped by the Earth's magnetic field and ultimately encircle the Earth, where they form a billion-degree plasma cloud around the planet, represented by the red cloud in Image 4. The blue doughnut shape in Image 4 represents the high-speed flow of these particles around the Earth. The red "ring of fire" around the Earth's polar regions represents the contribution of the particles to the aurora (the northern and southern lights).

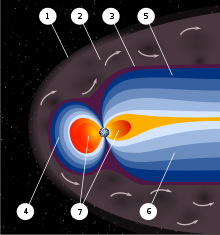

Artist's concept of the Earth's magnetosphere.

The rounded, bullet-like shape represents the bow shock as the magnetosphere confronts solar winds. The area represented in gray, between the magnetosphere and the bow shock, is called the magnetosheath, while the magnetopause is the boundary between the magnetosphere and the magnetosheath.

The Earth's magnetosphere extends about 10 Earth radii toward the Sun and perhaps similar distances outward on the flanks. The magnetotail is thought to extend as far as 1,000 Earth radii away from the Sun.

- 1 : Bow shock

- 2 : Magnetosheath

- 3 : Magnetopause

- 4 : Magnetosphere

- 5 : Northern tail lobe

- 6 : Southern tail lobe

- 7 : Plasmasphere