Planum Boreum

| Ebene auf dem Mars | ||

|---|---|---|

| Planum Boreum | ||

| ||

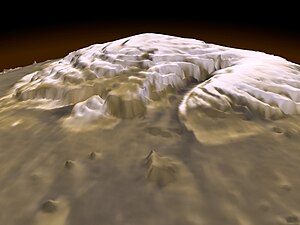

| 3D-Karte, berechnet aus Daten aufgenommen durch Mars Global Surveyor | ||

| Position | 87° 19′ N, 54° 58′ O | |

| Ausdehnung | 350 km | |

Als Planum Boreum wird das Gebiet um den Nordpol des Mars bezeichnet, welches von Vastitas Borealis umgürtet wird. Das Gegenstück am Südpol ist Planum Australe.[1]

Etymologie

Planum Boreum – die Nordebene – leitet sich ab vom Lateinischen Adjektiv planus (eben, flach) bzw. vom Altgriechischen πλάνος und von Boreas, das aus Βορέας, dem griechischen Gott des Nordwinds Boreas entlehnt ist.

Beschreibung

Planum Boreum liegt in einer breiten Senke (inoffiziell als Borealis-Becken bezeichnet) nördlich von 78,5° nördlicher Breite; es ist bei 88° Nord und 15° Ost zentriert. Das südlich anschließende, 1400 Kilometer breite Band der Vastitas Borealis reicht bis 54,7° nördlicher Breite herab und dominiert die Nordhemisphäre. Planum Boreum wird durch die domartigen, bis zu 2, maximal 3 Kilometer dicken Eisschichten der nördlichen Eiskappe bestimmt, die hauptsächlich aus Wassereis und etwas Staub (von fein bis grobkörnig) aufgebaut sind. Während des Nordwinters wird die Eiskappe von einer dünnen, 1 Meter mächtigen Trockeneislage (festes Kohlenstoffdioxid) verhüllt. Das Gesamtvolumen der Eiskappe beträgt 1,12 Millionen Kubikkilometer. Ihre Oberfläche ist eineinhalb mal so groß wie Texas und hat einen Durchmesser von 1200 Kilometer. Die Ausdehnung der Eismassen unterliegt jahreszeitlichen Schwankungen mit einem Maximum zu Beginn des Marsfrühjahrs und einem Minimum im Spätsommer.

Planum Boreum bildet eine extrem flache Senke. Berechnungen zeigen, dass es mit einer Lithosphärendicke von mehr als 300 Kilometer im Flexurgleichgewicht steht.[2]

Auffällig sind die Spiralfurchen – spiralförmige Einschnitte der Eisdecke – einschließlich des 460 km langen, bis zu 100 km breiten und etwa 2 km tiefen Grabens Chasma Boreale (82° 32′ N, 47° 38′ W). Die Spiralfurchen entstanden durch die Einwirkung katabatischer Fallwinde im Zusammenwirken mit Ablation bzw. Sublimation durch Sonneneinstrahlung. Die katabatischen Winde blasen das Eis äquatorwärts aus und lagern es an polwärts geneigten Hängen wieder ab. Die Furchen sind nahezu senkrecht zur Windrichtung angeordnet. Durch die Coriolis-Kraft werden die vom Nordpol nach Süden wehenden Winde abgelenkt, wodurch ein Spiralmuster entsteht.[3] Im Verlauf der Zeit wandern die Spiralfurchen in Richtung Nordpol – so haben sich die im Zentralbereich liegenden Furchen in den letzten 2 Millionen Jahren um 65 Kilometer verlagert. Chasma Boreale ist ein wesentlich älteres und weit größeres Canyon, das parallel zur vorherrschenden Windrichtung verläuft.

Die Oberflächenzusammensetzung der Nordpolkappe wurde im Marsfrühjahr nach der im Winter erfolgten Trockeneisakkumulation von der Umlaufbahn aus untersucht. Die vorwiegend aus Wassereis bestehenden Außenränder der Eiskappe sind mit bis zu 0,15 % Staub verunreinigt. Bei Annäherung an den Pol nimmt der Wassereisgehalt der Oberfläche ab und wird durch Trockeneis ersetzt. Gleichzeitig verringert sich auch der Staubanteil. Am Pol selbst ist die Oberfläche im Wesentlichen reines Trockeneis mit einem minimalen Anteil von 30 ppm Wassereis.[4]

Markante Geländeformen

Herausstechendstes Geländemerkmal des Planum Boreum ist zweifellos Chasma Boreale, ein riesiger Graben in der Nordpolkappe. Das 100 Kilometer breite und bis zu 2 Kilometer tiefe Canyon hat an seinen Seitenwänden das Oberflächeneis und die Nordpolschichtablagerungen freigelegt. Westlich von Chasma Boreale bildet das Planum Boreum gegenüber dem Tiefland der Vastitas Borealis eine markante Geländestufe, die gewöhnlich 250 bis 300 und stellenweise bis zu 1000 Meter Höhe erreichen kann. Weiter außerhalb löst sich diese dann in einer Ansammlung von Mesas und Trögen auf. Die südlich durch Chasma Boreale abgetrennte Eiszunge wird als Gemina Lingula bezeichnet.

Südlich von Planum Boreum schließt sich das Olympia Planum an, das zwischen 85° und 75° nördlicher Breite von riesigen Sanddünenfeldern, den Olympia Undae, ausgefüllt wird. Weitere Dünenfelder sind Abalos Undae und Hyperboreae Undae. Olympia Undae, das größte dieser Felder, erstreckt sich von 100° bis 240° Länge, Abalos Undae liegt zwischen 261° und 280° Länge und Hyperboreae Undae zwischen 311° und 341° Länge.

Lawinen

HiRISE konnte vier Lawinenabgänge über eine 700 Meter hohe Steilwand beobachten. Die Staubwolke feinen Suspensionsmaterials ist 180 Meter breit und erreicht vom Wandfuß aus gemessen eine Entfernung von 190 Meter. Die roten Schichten enthalten Wassereis, wohingegen die weißen Schichten aus winterlichem Kohlendioxidfrost bestehen. Die Lawine ist offensichtlich von der obersten roten Schicht abgegangen. Nachfolgeuntersuchungen sollen Klarheit über die Natur der Ablagerungen erbringen.

Wiederkehrende Ringwolke

Jedes Marsjahr erscheint in etwa zum selben Zeitpunkt über der Nordpolregion eine Ringwolke von konstanter Größe. Sie bildet sich am Morgen und löst sich dann im Verlauf des Nachmittags wieder auf. Der Außendurchmesser der Wolke beträgt rund 1000 Kilometer, der Durchmesser des inneren Auges 320 Kilometer. Da diese Ringwolke wahrscheinlich Wassereis enthält, weist sie im Unterschied zu Staubstürmen eine weiße Farbe auf.

Die Ringwolke ähnelt einem zyklonischen Hurrikan, zeigt aber keine Rotationsbewegung. Sie erscheint während des Nordsommers in hohen Breiten. Ihre Entstehung dürfte mit den einzigartigen klimatischen Bedingungen am Nordpol in Verbindung stehen.[5] Zyklone auf dem Mars wurden bereits von den Viking-Sonden aufgenommen, die Ringwolke besitzt jedoch dreimal so große Ausmaße. Die Ringwolke wurde von verschiedenen Sonden registriert, unter anderen auch von Hubble im Jahr 1999 und von Mars Global Surveyor.

Areologie

Der areologische Untergrund des Planum Boreum wird von Schichtablagerungen des Hesperiums gebildet (Einheit Hpu). Die Schichtpakete im Dekameterbereich sind im Talboden des Chasma Boreale und in den Rupes Tenuis aufgeschlossen. Überlagert werden sie von den Schichtablagerungen des Amazoniums (Einheit Apu), die den Hauptteil des Eisschildes aufbauen. Darüber legen sich die jungamazonischen Eislagen (Einheit lApc), die nicht mehr als 2 Meter mächtig werden. Die jungamazonischen Sanddünenformationen wie beispielsweise die Olympia Dunae (Einheit lApd) liegen außerhalb des Eisschildes. Anzutreffen sind Seif-, Barchan- und andere Dünentypen im Dekameterbereich, auch Permafrosterscheinungen sind keine Seltenheit. Sie überdecken entweder späthesperische Tieflandsedimente lHl, hesperische Schichtablagerungen Hpu, mittel- bis spätamazonische Schichtablagerungen des Eisschildes Apu oder raue hesperische Konstrukte Hpe der Scandia Cavi und Scandia Tholi.

Dem jungamazonischen Eisschild wird ein Alter von weniger als 10 Millionen Jahren zugewiesen.[6]

Weblinks

- Naturwunder, Mathias Scholz: Planet Mars (20) - Die Nordpolarkappe, Oktober 2011

- Naturwunder, Mathias Scholz: Planet Mars (19) - Polarkappen, Oktober 2011

- science.orf.at: Wind formte den Nordpol des Mars

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Planum Boreum im Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature der IAU (WGPSN) / USGS

- ↑ R. J. Phillips u. a.: Mars north polar deposits: Stratigraphy, age, and geodynamical response. In: Science. Band 320, 2008, S. 1182–1185.

- ↑ Isaac B. Smith, J. W. Holt: Onset and migration of spiral troughs on Mars revealed by orbital radar. In: Nature. Band 465, Nr. 4, 2010, S. 450–453, doi:10.1038/nature09049 (nature.com).

- ↑ G. Granada: Spatial variability and composition of the seasonal north polar cap on Mars. 2006 (jussieu.fr [PDF]).

- ↑ D. Brand, R. Villard: Colossal cyclone swirling near Martian north pole is observed by Cornell-led team on Hubble telescope. (Memento vom 5. August 2012 im Webarchiv archive.today) In: Cornell News. 1999.

- ↑ P. Thomas u. a.: Polar deposits of Mars. In: H. H. Kieffer u. a. (Hrsg.): Mars. Univ. of Arizona Press, Tucson 1992, S. 767–795.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

An impact crater on Planum Boreum, or Nort Polar Cap, of Mars, observed by HiRISE on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The crater is approximately 115 meters (380 feet) across. Craters on the polar cap are rare and it is thought that the surrounding ice relaxes with time, making craters dissapear.

Topography of Mars' northern hemisphere in polar stereographic projection with informal place names.

In spring, the sublimation of the ice (going directly from ice to gas) causes a host of uniquely Martian phenomena. In this image streaks of dark basaltic sand have been carried from below the ice layer to form fan-shaped deposits on top of the seasonal ice. The similarity in the directions of the fans suggests that they formed at the same time, when the wind direction and speed was the same. They often form along the boundary between the dune and the surface below.

This first three-dimensional picture of Mars' north pole enables scientists to estimate the volume of its water ice cap with unprecedented precision, and to study its surface variations and the heights of clouds in the region for the first time.

Approximately 2.6 million of these laser pulse measurements were assembled into a topographic grid of the North pole with a spatial resolution of 0.6 miles (one kilometer) and a vertical accuracy of 15-90 feet (5-30 meters). The principal investigator for MOLA is Dr. David E. Smith of Goddard.

The MOLA instrument was designed and built by the Laser Remote Sensing Branch of the Laboratory for Terrestrial Physics at Goddard. The Mars Global Surveyor Mission is managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA, for the NASA Office of Space Science, Washington, DC.Defrosted Margin of the North Polar Erg of Planum Boreum, or North Pole of Mars, observed by HiRISE on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The erg is a "sea of sand" that surrounds the north polar car. Polygonal dunes imply wind blowing from different directions over time.

During the last week of September and the first week or so of October 2006, scientific instruments on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter were turned on to acquire test information during the transition phase leading up to full science operations. The mission's primary science phase will begin the first week of November 2006, following superior conjunction. (Superior conjunction is where a planet goes behind the sun as viewed from Earth.) Since it is very difficult to communicate with a spacecraft when it is close to the sun as seen from Earth, this checkout of the instruments was crucial to being ready for the primary science phase of the mission.

Throughout the transition-phase testing, the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) acquired terminator (transition between nighttime and daytime) to terminator swaths of color images on every dayside orbit, as the spacecraft moved northward in its orbit. The south polar region was deep in winter shadow, but the north polar region was illuminated the entire Martian day. During the primary mission, such swaths will be assembled into global maps that portray the state of the Martian atmosphere -- its weather -- as seen every day and at every place at about 3 p.m. local solar time. After the transition phase completed, most of the instruments were turned off, but the Mars Climate Sounder and MARCI have been left on. Their data will be recorded and played back to Earth following the communications blackout associated with conjunction.

Combined with wide-angle image mosaics taken by the Mars Orbiter Camera on NASA's Mars Global Surveyor at 2 p.m. local solar time, the MARCI maps will be used to track motions of clouds.

This image is a composite mosaic of four polar views of Mars, taken at midnight, 6 a.m., noon, and 6 p.m. local Martian time. This is possible because during summer the sun is always shining in the polar region. It shows the mostly water-ice perennial cap (white area), sitting atop the north polar layered materials (light tan immediately adjacent to the ice), and the dark circumpolar dunes. This view shows the region poleward of about 72 degrees north latitude. The data were acquired at about 900 meters (about 3,000 feet) per pixel. Three channels are shown here, centered on wavelengths of 425 nanometers, 550 nanometers and 600 nanometers.Carte de Mars reconstituée à partir des mesures de Mars Global Surveyor (MOLA) et des observations de Viking.

Original Caption Released with Image:

[left]: Here is the discovery image of the Martian polar storm as seen in blue light (410 nm). The storm is located near 65 deg. N latitude and 85 deg. W longitude, and is more than 1000 miles (1600 km) across. The residual north polar water ice cap is at the top of the image. A belt of clouds like that seen in previous telescopic observations during this Martian season can also be seen in the planet's equatorial regions and northern mid-latitudes, as well as in the southern polar regions. The volcano Ascraeus Mons can be seen as a dark spot poking above the cloud deck near the western (morning) limb. This extinct volcano towers nearly 16 miles (25 km) above the surrounding plains and is about 250 miles (400 km) across.

[upper right]: This is a color polar view of the north polar region, showing the location of the storm relative to the classical bright and dark features in this area. The color composite data (410, 502, and 673 nm) indicate that the storm is fairly dust-free and therefore likely composed mostly of water ice clouds. The bright surface region beneath the eye of the storm can be seen clearly. This map covers the region north of 45 degrees latitude and is oriented with 0 degrees longitude at the bottom.

[lower right]: This is an enhanced orthographic view of the storm centered on 65 deg. N latitude, 85 deg. W longitude. The image has been processed to bring out additional detail in the storm's spiral cloud structures.

The pictures were taken on April 27, 1999 with the NASA Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2Linear Dunes in the North Polar Region of Mars (Planum Boreum), observed by HiRISE on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Stratigraphy of the North Polar Deposits of Planum Boreum, or North Polar deposits of Mars, observed by HiRISE on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Deposits consist mainly of water ice and small amounts of dust. Image is approximately 1km (3300 feet) across.

Avalanches on Mars.

This striking image of a mound within the area of a trough cutting into Mars' north polar layered deposits was taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on September 2, 2008.

The north polar layered deposits are a stack of discernible layers that are rich in water-ice. The stack is up to several miles thick. Each layer is thought to contain information about the climate that existed when it was deposited. If true, the stack could represent a record of how climate has varied on Mars in the recent past. The internal layers are exposed in troughs and scarps where erosion has cut into the stack. The trough shown in this image contains a 1,640-foot thick section of the layering.

A conical mound partway down the slope stands approximately 130 feet high. One possible explanation for this unusual mound is that it may be the remnant of a buried impact crater now being exhumed. As the north polar layered deposits accumulated, impacts occurred throughout their surface area, then the impact craters were buried by additional ice. These buried craters are generally inaccessible, but, in a few locations, erosion that forms a trough (like this one) can uncover these buried structures. For reasons poorly understood, the ice beneath the site of the crater is more resistant to this erosion, so when material is removed by erosion the ice beneath the old impact site remains, forming this isolated hill.An impact crater on Planum Boreum, or North Polar deposits of Mars, observed by HiRISE on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The crater is approximately 130 meters (425 feet) across and has been filled with dust and ice.