Pinene

Pinene (Betonung auf der zweiten Silbe: Pinen) sind eine Gruppe isomerer Monoterpen-Kohlenwasserstoffe, die als farblose Flüssigkeiten vorliegen und Bestandteile ätherischer Öle sind. Die Struktur leitet sich von der gesättigten Verbindung Pinan ab.

Geschichte

1907 wurden von Otto Wallach drei Pinene als α, β- und γ-Pinen zugeordnet.[1] 1921 wurde ein weiterer Vertreter entdeckt und folglich als δ-Pinen bezeichnet.[2] Die von Wallach zugeordnete Konstitution von „γ-Pinen“ wurde 1947 durch Harry Schmidt wieder verworfen,[3] da sie der Bredtschen Regel widerspricht. Die genannten klassischen Bezeichnungen der Pinene (α, β, γ, δ) wurden trotzdem beibehalten, da sie sich bereits zu jener Zeit in der Literatur eingebürgert hatten.

Vertreter

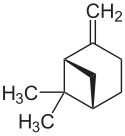

Bekannt sind sechs Pinen-Isomere, je zwei Enantiomere von α-Pinen und β-Pinen sowie zwei Isomere von δ-Pinen, in der Literatur als (+)-cis-δ-Pinen und (–)-cis-δ-Pinen beschrieben.[4]

| Pinene | ||||||||||||||||||

| Name | (+)-α-Pinen | (−)-α-Pinen | (+)-β-Pinen | (−)-β-Pinen | (+)-cis-δ-Pinen | (−)-cis-δ-Pinen | ||||||||||||

| Andere Namen | Pin-2(3)-en 2-Pinen 2,6,6-Trimethylbicyclo- [3.1.1]hept-2-en | Pin-2(10)-en 2(10)-Pinen Nopinen Pseudopinen 6,6-Dimethyl-2-methylenbicyclo- [3.1.1]heptan | ||||||||||||||||

| Pinen, DIDEHYDROPINANE (INCI)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Strukturformel |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||||||||

| CAS-Nummer | 7785-70-8 | 7785-26-4 | 19902-08-0 | 18172-67-3 | ||||||||||||||

| 80-56-8 (unspezifiziert) | 127-91-3 (unspezifiziert) | |||||||||||||||||

| 1330-16-1 (Isomerengemisch) | ||||||||||||||||||

| PubChem | 82227 | 440968 | 10290825 | 440967 | 12314302 | |||||||||||||

| Summenformel | C10H16 | |||||||||||||||||

| Molare Masse | 136,24 g·mol−1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Aggregatzustand | flüssig | |||||||||||||||||

| Kurzbeschreibung | farblose Flüssigkeit mit terpentinartigem Geruch[6][7] | |||||||||||||||||

| Schmelzpunkt | −55 °C[6] | −61 °C[7] | ||||||||||||||||

| Siedepunkt | 155 °C[6] | 165–166 °C[7] | ||||||||||||||||

| Dichte | 0,86 g·cm−3 (15 °C)[6] | 0,87 g·cm−3 (20 °C)[8] | ||||||||||||||||

| Dampfdruck | 5 hPa (25 °C)[6] | 2,66 hPa | ||||||||||||||||

| Löslichkeit | praktisch unlöslich in Wasser[6][7] | |||||||||||||||||

| Brechungsindex | 1,4653 (20 °C)[8] | 1,4768 (20 °C)[8] | ||||||||||||||||

| Flammpunkt | 33 °C[6] | 36 °C[7] | ||||||||||||||||

| GHS- Kennzeichnung |

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

| H- und P-Sätze | 226‐304‐315‐317‐410 | 226‐315‐319‐335 | 226‐304‐315‐317‐410 | siehe oben | siehe oben | |||||||||||||

| keine EUH-Sätze | keine EUH-Sätze | keine EUH-Sätze | siehe oben | siehe oben | ||||||||||||||

| 210‐273‐280‐301+310‐303+361+353‐331 | 310‐302+352‐305+351+338 | 210‐273‐280‐301+310+331‐302+352 | siehe oben | siehe oben | ||||||||||||||

Vorkommen

Die α- und β-Pinene kommen in den ätherischen Ölen zahlreicher Pflanzen vor, unter anderem bei vielen Koniferen, wo der Anteil bis zu 90 % ausmacht.[10][11] In der Waldkiefer ist α(+)-Pinen die Hauptkomponente, während β-Pinen in geringer Menge vorkommt.[12][13] In der Fichte kommt vor allem α-(–)-Pinen vor.[13] α- und β-Pinen machen auch den Hauptbestandteil von Terpentin bzw. Terpentinöl aus, die aus Koniferen gewonnen werden.[10][14] Das ätherische Öl der Libanon-Zeder enthält etwa 39,7 % α-Pinen und 14,7 % β-Pinen, das der Mittelmeer-Zypresse etwa 57,5 % α-Pinen und 3 % β-Pinen.[11] Außerdem kommen Pinene in den Ölen von Sumpf-Kiefer[15], Wacholder[16], mehrerer Eucalyptus-Arten (α- und β-Pinen in E. grandis[17] und E. tereticornis[18], β-Pinen E. camaldulensis[19]) sowie von Pinus kesiya, Pinus gerardiana und Pinus roxburghii[20][21] vor.

α- und β-Pinen gehören zu den wichtigsten Komponenten des ätherischen Öls aus Pfefferkörnern (Piper nigrum).[22] Außerdem gehören sie zu den wichtigsten Terpenen in Cannabis[23][24] und kommen in Dill[25], Sternanis,[26] Moschus-Erdbeeren,[27] Wermutkraut[28], in der Myrte (Myrtus communis)[29], Fenchel (Foeniculum vulgare)[30], manchmal in Petersilie (Petroselinum crispum)[31], Guave (Psidium guajava)[32], sowie Koriander (Coriandrum sativum)[33] vor.

Das ätherische Öl von Boswellia sacra besteht zu etwa zwei Dritteln aus α-Pinen, außerdem sind einige Prozent β-Pinen enthalten.[34] Das von Rosmarin (Rosmarinus officinalis) enthält bis über 50 % α-Pinen[35], das von Muskatnuss (Myristica fragrans) je etwa 10 % α- und β-Pinen[36], das von Sellerie (Apium graveolens) enthält ebenfalls α- und β-Pinen[37], das von Kreuzkümmel (Cuminum cyminum) vor allem β-Pinen[38], das von Kümmel kleine Mengen α-Pinen.[39]

α-Pinen ist eine wichtige Komponente im Sexualpheromon der weiblichen Olivenfruchtfliege.[40] Propolis enthält bis zu 46 % α-Pinen und bis zu 21 % β-Pinen.[41]

α-Pinen gehört neben Toluol zu den mengenmäßig wichtigsten flüchtigen Verbindungen, die von Möbeln abgesondert werden.[42]

- Waldkiefer

- Pfefferkörner

- Myrte

- Fenchel

- Boswellia sacra

- Muskatnuss

- Olivenfruchtfliege

Biosynthese

α-Pinen und β-Pinen werden beide aus Geranylpyrophosphat durch Cyclisierung von Linalool-pyrophosphat gefolgt durch Umlagerung eines Wasserstoffatoms synthetisiert.

Synthese

α- und β-Pinen können ausgehend vom Hagemann-Ester synthetisiert werden.[43]

Eigenschaften

Pinene sind wenig flüchtige, entzündliche, klare Flüssigkeiten mit terpentinartigem Geruch, weniger dicht als Wasser, und in Wasser unlöslich.[6][7] Ihre Schmelz- und Siedetemperaturen sowie ihre Dichten unterscheiden sich nur geringfügig. α-Pinen oxidiert üblicherweise zu Verbenon, Myrtenol, Pinenoxid und weiteren Produkten.[44]

Toxikologie

α-Pinen in höheren Dosen wird durch seine Reizwirkung auf Augen, Atemwege und Haut, und mögliche neuro- und nephrotoxische Wirkungen als gesundheitsschädlich eingestuft. Auch β-Pinen wirkt reizend.

Risikobewertung

Pin-2(10)-en wurde 2014 von der EU gemäß der Verordnung (EG) Nr. 1907/2006 (REACH) im Rahmen der Stoffbewertung in den fortlaufenden Aktionsplan der Gemeinschaft (CoRAP) aufgenommen. Hierbei werden die Auswirkungen des Stoffs auf die menschliche Gesundheit bzw. die Umwelt neu bewertet und ggf. Folgemaßnahmen eingeleitet. Ursächlich für die Aufnahme von Pin-2(10)-en waren die Besorgnisse bezüglich Verbraucherverwendung, hoher (aggregierter) Tonnage und weit verbreiteter Verwendung sowie der vermuteten Gefahren durch sensibilisierende Eigenschaften. Die Neubewertung fand ab 2014 statt und wurde von Griechenland durchgeführt. Anschließend wurde ein Abschlussbericht veröffentlicht.[45][46]

Pharmakologische Eigenschaften

α-Pinen hat in verschiedenen Studien (vor allem in vitro) Wirkungen gezeigt (z. B. antibakteriell, fungizid und gegen Krebs), durch die es sich möglicherweise für eine zukünftige medizinische Anwendung eignet. Die Wirkungen sind je nach Stereoisomer unterschiedlich ausgeprägt.[47] α-Pinen wirkt möglicherweise antientzündlich[48] und zumindest in vitro antimikrobiell[49] und fungizid gegen Arten der Gattung Candida.[50] In niedrigen Dosen wirkt α-Pinen bronchospasmolytisch.[51] α-(+)-, α-(–)- und β-(–)-Pinen wirken in vitro als Inhibitoren der Acetylcholinesterase.[52]

Es gibt Hinweise, dass Terpene im Allgemeinen und (+)-α-Pinen im Besonderen möglicherweise die pharmakologischen Effekte von Cannabinoiden (z. B. Cannabidiol) verstärken, was als Entourage-Effekt bezeichnet wird. Die Existenz dieses Effekts ist allerdings umstritten, insbesondere gibt es bisher keine klinischen Studien, die ihn belegen.[47][53][54]

Verwendung

Pinene werden als Aromastoffe verwendet. In der EU ist α-Pinen unter der FL-Nummer 01.004 als Aromastoff für Lebensmittel allgemein zugelassen.[55] Eine analoge Zulassung besteht für β-Pinen unter der FL-Nummer 01.003.[56] Die Geruchsschwelle von α-Pinen ist etwa 2,5-62 ppb, die Geschmacksschwelle etwa 10 ppm; die jährliche Verwendung (unter anderem zur Aromatisierung von Bonbons und Kaugummi) liegt über zehn Tonnen. Bei β-Pinen liegt die Geruchsschwelle bei 140 ppb, die Geschmacksschwelle bei 15-100 ppm und die Verwendungsmenge bei einigen Tonnen pro Jahr.[10]

Pinene können als Edukte für die Synthese diverser weiterer Verbindungen dienen. Säurekatalysiert (mit Essigsäure und Phosphorsäure) oder durch mikrobielle Umwandlungen können α- und β-Pinen zu Terpineol umgesetzt werden.[10][57][58] Aus α-Pinen können Verbenol und Verbenon biotechnologisch gewonnen werden.[10] Auch Aminosäurederivate[59] und andere Verbindungen[60] können ausgehend von Pinenen hergestellt werden.

Nachweis

Zur zuverlässigen qualitativen und quantitativen Bestimmung kommt nach angemessener Probenvorbereitung die Kopplung von Gaschromatographie und Massenspektrometrie zum Einsatz.[61][62] Auch die Anwendung der Olfaktometrie wird zur Identifizierung und Charakterisierung herangezogen.[63]

Literatur

- Dennis Hobuß: α- und β-Pinen: Vielseitige chirale Kohlenstoffgerüste für die asymmetrische Katalyse. WiKu-Wissenschaftsverlag Dr. Stein, Duisburg/ Köln 2007, ISBN 978-3-86553-225-1.

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ O. Wallach, Arnold Blumann: Zur Kenntnis der Terpene und der ätherischen Oele Ueber Nopinon. In: Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. Band 356, Nr. 1–2, 1907, S. 227–249, doi:10.1002/jlac.19073560111.

- ↑ A. Blumann, O. Zeitschel: Über Verbenen (Dehydro‐α‐pinen) und einige seiner Abkömmlinge. In: Chemische Berichte. Band 54, Nr. 5, 1921, S. 887–894, doi:10.1002/cber.19210540504.

- ↑ Harry Schmidt: Zur Raumisomerie in der Pinanreihe, VI. Mitteil.: cis- und trans-δ-Pinen. In: Chemische Berichte. 80(6), 1947, S. 520–527. doi:10.1002/cber.19470800610

- ↑ Z. Szakonyia u. a.: Regio- and stereoselective synthesis of the enantiomers of monoterpene-based β-amino acid derivatives. In: Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 18(20), 2007, S. 2442–2447, doi:10.1016/j.tetasy.2007.09.028.

- ↑ Eintrag zu DIDEHYDROPINANE in der CosIng-Datenbank der EU-Kommission, abgerufen am 24. November 2021.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Eintrag zu alpha-Pinen in der GESTIS-Stoffdatenbank des IFA, abgerufen am 3. Januar 2023. (JavaScript erforderlich)

- ↑ a b c d e f g Eintrag zu beta-Pinen in der GESTIS-Stoffdatenbank des IFA, abgerufen am 3. Januar 2023. (JavaScript erforderlich)

- ↑ a b c R. T. O’Connor, L. A. Goldblatt: Correlation of Ultraviolet and Infrared Spectra of Terpene Hydrocarbons. In: Anal. Chem. 26, 1954, S. 1726–1737. doi:10.1021/ac60095a014.

- ↑ Datenblatt (+)-β-Pinene bei Sigma-Aldrich, abgerufen am 30. August 2018 (PDF).

- ↑ a b c d e Kele A. C. Vespermann, Bruno N. Paulino, Mayara C. S. Barcelos, Marina G. Pessôa, Glaucia M. Pastore, Gustavo Molina: Biotransformation of α- and β-pinene into flavor compounds. In: Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. Band 101, Nr. 5, März 2017, S. 1805–1817, doi:10.1007/s00253-016-8066-7.

- ↑ a b Layal Fahed, Madona Khoury, Didier Stien, Naïm Ouaini, Véronique Eparvier, Marc El Beyrouthy: Essential Oils Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Six Conifers Harvested in Lebanon. In: Chemistry & Biodiversity. Band 14, Nr. 2, Februar 2017, S. e1600235, doi:10.1002/cbdv.201600235.

- ↑ Martina Allenspach, Claudia Valder, Daniela Flamm, Francesca Grisoni, Christian Steuer: Verification of Chromatographic Profile of Primary Essential Oil of Pinus sylvestris L. Combined with Chemometric Analysis. In: Molecules. Band 25, Nr. 13, 28. Juni 2020, S. 2973, doi:10.3390/molecules25132973, PMID 32605289, PMC 7411901 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ a b Kristina Sjödin, Monika Persson, Jenny Fäldt, Inger Ekberg, Anna-Karin Borg-Karlson: [No title found]. In: Journal of Chemical Ecology. Band 26, Nr. 7, 2000, S. 1701–1720, doi:10.1023/A:1005547131427.

- ↑ Shou-Ji Zhu, Shi-Chao Xu, Zhen-Dong Zhao: An efficient synthesis method targeted to a novel aziridine derivative of p-menthane from turpentine and its herbicidal activity. In: Natural Product Research. Band 31, Nr. 13, 3. Juli 2017, S. 1536–1543, doi:10.1080/14786419.2017.1280494.

- ↑ Karl‐Georg Fahlbusch, Franz‐Josef Hammerschmidt, Johannes Panten, Wilhelm Pickenhagen, Dietmar Schatkowski, Kurt Bauer, Dorothea Garbe, Horst Surburg: Flavors and Fragrances. In: Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Band 15, 2012, S. 73–198, doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_141.

- ↑ R. Hiltunen, I. Laakso: Gas chromatographic analysis and biogenetic relationships of monoterpene enantiomers in Scots Pine and juniper needle oils. In: Flavour and Fragrance Journal. Band 10, Nr. 3, Mai 1995, S. 203, doi:10.1002/ffj.2730100314.

- ↑ Alejandro Lucia, Paola Gonzalez Audino, Emilia Seccacini, Susana Licastro, Eduardo Zerba, Hector Masuh: LARVICIDAL EFFECT OF EUCALYPTUS GRANDIS ESSENTIAL OIL AND TURPENTINE AND THEIR MAJOR COMPONENTS ON AEDES AEGYPTI LARVAE. In: Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. Band 23, Nr. 3, September 2007, S. 299–303, doi:10.2987/8756-971X(2007)23[299:LEOEGE]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Davi Matthews Jucá, Moisés da Silva, Raimundo Palheta Junior, Francisco de Lima, Willy Okoba, Saad Lahlou, Ricardo de Oliveira, Armênio dos Santos, Pedro Magalhães: The Essential Oil of Eucalyptus tereticornis and its Constituents, α- and β-Pinene, Show Accelerative Properties on Rat Gastrointestinal Transit. In: Planta Medica. Band 77, Nr. 01, Januar 2011, S. 57–59, doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250116.

- ↑ Andreas Giamakis, Ourania Kretsi, Ioanna Chinou, Caroline G. Spyropoulos: Eucalyptus camaldulensis: volatiles from immature flowers and high production of 1,8-cineole and β-pinene by in vitro cultures. In: Phytochemistry. Band 58, Nr. 2, September 2001, S. 351–355, doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00193-5.

- ↑ ALPHA-PINENE (englisch). In: Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database, Hrsg. U.S. Department of Agriculture, abgerufen am 29. August 2021.

- ↑ BETA-PINENE (englisch). In: Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database, Hrsg. U.S. Department of Agriculture, abgerufen am 29. August 2021.

- ↑ Dosoky, Satyal, Barata, da Silva, Setzer: Volatiles of Black Pepper Fruits (Piper nigrum L.). In: Molecules. Band 24, Nr. 23, 21. November 2019, S. 4244, doi:10.3390/molecules24234244, PMID 31766491, PMC 6930617 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Nils Günnewich, Jonathan E. Page, Tobias G. Köllner, Jörg Degenhardt, Toni M. Kutchan: Functional Expression and Characterization of Trichome-Specific (–)-Limonene Synthase and (+)-α-Pinene Synthase from Cannabis sativa. In: Natural Product Communications. Band 2, Nr. 3, März 2007, S. 1934578X0700200, doi:10.1177/1934578X0700200301.

- ↑ Eric P. Baron: Medicinal Properties of Cannabinoids, Terpenes, and Flavonoids in Cannabis, and Benefits in Migraine, Headache, and Pain: An Update on Current Evidence and Cannabis Science. In: Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. Band 58, Nr. 7, Juli 2018, S. 1139–1186, doi:10.1111/head.13345.

- ↑ Robert J. Clark, Robert C. Menary: The effect of harvest date on the yield and composition of Tasmanian dill oil (Anethum graveolens L.). In: Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Band 35, Nr. 11, November 1984, S. 1188, doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740351108.

- ↑ Jayanta Kumar Patra, Gitishree Das, Sankhadip Bose, Sabyasachi Banerjee, Chethala N. Vishnuprasad, Maria Pilar Rodriguez‐Torres, Han‐Seung Shin: Star anise (Illicium verum): Chemical compounds, antiviral properties, and clinical relevance. In: Phytotherapy Research. Band 34, Nr. 6, Juni 2020, S. 1248–1267, doi:10.1002/ptr.6614.

- ↑ Friedrich Drawert, Roland Tressl, Günter Staudt, Hans Köppler: Gaschromatographisch-massenspektrometrische Differenzierung von Erdbeerarten. In: Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 28, 1973, S. 488–493 (PDF, freier Volltext).

- ↑ Otto Vostrowsky, Thorolf Brosche, Helmut Ihm, Robert Zintl, Karl Knobloch: Über die Komponenten des ätherischen Öls aus Artemisia absinthium L.. In: Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 36, 1981, S. 369–377 (PDF, freier Volltext).

- ↑ Bahman Fazeli-Nasab, Riyaz Z. Sayyed, Ali Sobhanizadeh: In Silico Molecular Docking Analysis of α-Pinene: An Antioxidant and Anticancer Drug Obtained from Myrtus communis. In: International Journal of Cancer Management. Band 14, Nr. 2, 1. März 2021, doi:10.5812/ijcm.89116.

- ↑ Petras Rimantas Venskutonis, Airidas Dapkevicius, Teris A. van Beek: Essential Oils of Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) from Lithuania. In: Journal of Essential Oil Research. Band 8, Nr. 2, März 1996, S. 211–213, doi:10.1080/10412905.1996.9700598.

- ↑ Sa Petropoulos, D Daferera, Ca Akoumianakis, Hc Passam, Mg Polissiou: The effect of sowing date and growth stage on the essential oil composition of three types of parsley(Petroselinum crispum). In: Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. Band 84, Nr. 12, September 2004, S. 1606–1610, doi:10.1002/jsfa.1846.

- ↑ Jorge A. Pino, Rolando Marbot, Carlos Vázquez: Characterization of Volatiles in Costa Rican Guava [ Psidium friedrichsthalianum (Berg) Niedenzu] Fruit. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 50, Nr. 21, 1. Oktober 2002, S. 6023–6026, doi:10.1021/jf011456i.

- ↑ Samad Nejad Ebrahimi, Javad Hadian, Hamid Ranjbar: Essential oil compositions of different accessions of Coriandrum sativum L. from Iran. In: Natural Product Research. Band 24, Nr. 14, 10. September 2010, S. 1287–1294, doi:10.1080/14786410903132316, PMID 20803372, PMC 2931356 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Cole L. Woolley, Mahmoud M. Suhail, Brett L. Smith, Karen E. Boren, Lindsey C. Taylor, Marc F. Schreuder, Jeremiah K. Chai, Hervé Casabianca, Sadqa Haq, Hsueh-Kung Lin, Ahmed A. Al-Shahri, Saif Al-Hatmi, D. Gary Young: Chemical differentiation of Boswellia sacra and Boswellia carterii essential oils by gas chromatography and chiral gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. In: Journal of Chromatography A. Band 1261, Oktober 2012, S. 158–163, doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2012.06.073.

- ↑ Arthur O. Tucker, Michael J. Maciarello: The essential oils of some rosemary cultivars. In: Flavour and Fragrance Journal. Band 1, Nr. 4–5, September 1986, S. 137–142, doi:10.1002/ffj.2730010402.

- ↑ Gomathi Periasamy, Aman Karim, Mebrahtom Gibrelibanos, Gereziher Gebremedhin, Anwar-ul-Hassan Gilani: Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans Houtt.) Oils. In: Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor and Safety. Elsevier, 2016, ISBN 978-0-12-416641-7, S. 607–616, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-416641-7.00069-9.

- ↑ Sameh Baananou, Ibtissem Bouftira, Amor Mahmoud, Kamel Boukef, Bruno Marongiu, Naceur A. Boughattas: Antiulcerogenic and antibacterial activities of Apium graveolens essential oil and extract. In: Natural Product Research. Band 27, Nr. 12, Juni 2013, S. 1075–1083, doi:10.1080/14786419.2012.717284.

- ↑ Nicola S. Iacobellis, Pietro Lo Cantore, Francesco Capasso, Felice Senatore: Antibacterial Activity of Cuminum cyminum L. and Carum carvi L. Essential Oils. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 53, Nr. 1, 1. Januar 2005, S. 57–61, doi:10.1021/jf0487351.

- ↑ Ain Raal, Elmar Arak, Anne Orav: The content and composition of the essential oil Found in Carum carvi L. commercial fruits obtained from different countries. In: Journal of Essential Oil Research. Band 24, Nr. 1, Februar 2012, S. 53–59, doi:10.1080/10412905.2012.646016.

- ↑ Christos D. Gerofotis, Charalampos S. Ioannou, Nikos T. Papadopoulos: Aromatized to Find Mates: α-Pinene Aroma Boosts the Mating Success of Adult Olive Fruit Flies. In: PLoS ONE. Band 8, Nr. 11, 19. November 2013, S. e81336, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081336, PMID 24260571, PMC 3834339 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Guy Kamatou, Maxleene Sandasi, Sidonie Tankeu, Sandy van Vuuren, Alvaro Viljoen: Headspace analysis and characterisation of South African propolis volatile compounds using GCxGC–ToF–MS. In: Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. Band 29, Nr. 3, Mai 2019, S. 351–357, doi:10.1016/j.bjp.2018.12.002.

- ↑ Duy Xuan Ho, Ki-Hyun Kim, Jong Ryeul Sohn, Youn Hee Oh, Ji-Won Ahn: Emission Rates of Volatile Organic Compounds Released from Newly Produced Household Furniture Products Using a Large-Scale Chamber Testing Method. In: The Scientific World JOURNAL. Band 11, 2011, S. 1597–1622, doi:10.1100/2011/650624, PMID 22125421, PMC 3201684 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Mary Alice Upshur, Marvin M. Vega, Ariana Gray Bé, Hilary M. Chase, Yue Zhang, Aashish Tuladhar, Zizwe A. Chase, Li Fu, Carlena J. Ebben, Zheming Wang, Scot T. Martin, Franz M. Geiger, Regan J. Thomson: Synthesis and surface spectroscopy of α-pinene isotopologues and their corresponding secondary organic material. In: Chemical Science. Band 10, Nr. 36, 2019, S. 8390–8398, doi:10.1039/C9SC02399B, PMID 31803417, PMC 6844218 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ U. Neuenschwander: Mechanism of the Aerobic Oxidation of α-Pinene. In: ChemSusChem. Band 3, Nr. 1, 2010, S. 75–84, doi:10.1002/cssc.200900228.

- ↑ Europäische Chemikalienagentur (ECHA): Substance Evaluation Conclusion and Evaluation Report, 2015.

- ↑ Community Rolling Action Plan (CoRAP) der Europäischen Chemikalienagentur (ECHA): (-)-pin-2(10)-ene, abgerufen am 20. Mai 2019.

- ↑ a b Martina Allenspach, Christian Steuer: α-Pinene: A never-ending story. In: Phytochemistry. Band 190, Oktober 2021, S. 112857, doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112857.

- ↑ Ethan B Russo: Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. In: British Journal of Pharmacology. Band 163, Nr. 7, 1. August 2011, S. 1344–1364, doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x, PMID 21749363, PMC 3165946 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Lorenzo Nissen, Alessandro Zatta, Ilaria Stefanini, Silvia Grandi, Barbara Sgorbati: Characterization and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of industrial hemp varieties (Cannabis sativa L.). In: Fitoterapia. Band 81, Nr. 5, 1. Juli 2010, S. 413–419, doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.11.010.

- ↑ Jefferson Rodrigues Nóbrega, Daniele de Figuerêdo Silva, Francisco Patricio de Andrade Júnior, Paula Mariane Silva Sousa, Pedro Thiago Ramalho de Figueiredo, Laísa Vilar Cordeiro, Edeltrudes de Oliveira Lima: Antifungal action of α-pinene against Candida spp. isolated from patients with otomycosis and effects of its association with boric acid. In: Natural Product Research. Band 35, Nr. 24, 17. Dezember 2021, S. 6190–6193, doi:10.1080/14786419.2020.1837803.

- ↑ A. A. Falk, M. T. Hagberg, A. E. Lof, E. M. Wigaeus-Hjelm, T. P. Wang: Uptake, distribution and elimination of alpha-pinene in man after exposure by inhalation. In: Scand J Work Environ Health. Band 16, 1990, S. 372–378, PMID 2255878.

- ↑ Mitsuo Miyazawa, Chikako Yamafuji: Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterase Activity by Bicyclic Monoterpenoids. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 53, Nr. 5, 1. März 2005, S. 1765–1768, doi:10.1021/jf040019b.

- ↑ Ethan B Russo: Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects: Phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. In: British Journal of Pharmacology. Band 163, Nr. 7, August 2011, S. 1344–1364, doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x, PMID 21749363, PMC 3165946 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Tarmo Nuutinen: Medicinal properties of terpenes found in Cannabis sativa and Humulus lupulus. In: European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. Band 157, September 2018, S. 198–228, doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.07.076.

- ↑ Food and Feed Information Portal Database | FIP. Abgerufen am 26. August 2023.

- ↑ Food and Feed Information Portal Database | FIP. Abgerufen am 26. August 2023.

- ↑ Tirto Prakoso, Jonathan Hanley, Mellisa Nathania Soebianta, Tatang Hernas Soerawidjaja, Antonius Indarto: Synthesis of Terpineol from α-Pinene Using Low-Price Acid Catalyst. In: Catalysis Letters. Band 148, Nr. 2, Februar 2018, S. 725–731, doi:10.1007/s10562-017-2267-2.

- ↑ Shi-Wei Liu, Shi-Tao Yu, Fu-Sheng Liu, Cong-Xia Xie, Lu Li, Kai-Hui Ji: Reactions of α-pinene using acidic ionic liquids as catalysts. In: Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical. Band 279, Nr. 2, 18. Januar 2008, S. 177–181, doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2007.06.026.

- ↑ Zsolt Szakonyi, Ferenc Fülöp: Monoterpene-based chiral β-amino acid derivatives prepared from natural sources: syntheses and applications. In: Amino Acids. Band 41, Nr. 3, August 2011, S. 597–608, doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0891-5.

- ↑ Ralf G. Berger: Biotechnology of flavours—the next generation. In: Biotechnology Letters. Band 31, Nr. 11, November 2009, S. 1651–1659, doi:10.1007/s10529-009-0083-5.

- ↑ Ivana Bonaccorsi, Danilo Sciarrone, Luisa Schipilliti, Paola Dugo, Luigi Mondello, Giovanni Dugo: Multidimensional enantio gas chromtography/mass spectrometry and gas chromatography–combustion-isotopic ratio mass spectrometry for the authenticity assessment of lime essential oils (C. aurantifolia Swingle and C. latifolia Tanaka). In: Journal of Chromatography A. Band 1226, Februar 2012, S. 87–95, doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.10.038.

- ↑ Hainan Sun, Ting Zhang, Qingqing Fan, Xiangyu Qi, Fei Zhang, Weimin Fang, Jiafu Jiang, Fadi Chen, Sumei Chen: Identification of Floral Scent in Chrysanthemum Cultivars and Wild Relatives by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. In: Molecules. Band 20, Nr. 4, 25. März 2015, S. 5346–5359, doi:10.3390/molecules20045346, PMID 25816078, PMC 6272594 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Zuobing Xiao, Binbin Fan, Yunwei Niu, Minling Wu, Junhua Liu, Shengtao Ma: Characterization of odor-active compounds of various Chrysanthemum essential oils by gas chromatography–olfactometry, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and their correlation with sensory attributes. In: Journal of Chromatography B. Band 1009-1010, Januar 2016, S. 152–162, doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.12.029.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) pictogram for flammable substances

Globales Harmonisiertes System zur Einstufung und Kennzeichnung von Chemikalien (GHS) Piktogramm für gesundheitsgefährdende Stoffe.

Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) pictogram for environmentally hazardous substances

Autor/Urheber: Katja Schulz, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

olive fruit fly (Bactrocera oleae)

Autor/Urheber:

This photo was taken by Ryan Bushby(HighInBC) with his Canon PowerShot S3 IS. To see more of his photos see his gallery.

Flowers of wild fennel

(-)-cis-delta-Pinen; (-)-cis-δ-Pinen

Autor/Urheber: Mauro Raffaelli, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Papery bark of Boswellia sacra (from Dhofar, Oman)

Autor/Urheber: WikiVagant, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Waldkiefer am Grenzweg Bollersdorf-Ernsthof, ca. 100 m östlich der Bundesstraße 168, Märkisch-Oderland, Brandenburg, Germany. Naturdenkmal Märkisch-Oderland Nr. 22

(c) Sugeesh in der Wikipedia auf Malayalam, CC BY-SA 3.0

Piper nigrum (Black Pepper)

der Bredtschen Regel widersprechende Struktur von sogenannten gamma-Pinen, was es so nicht gibt.

Struktur von (−)-beta-Pinen

Struktur von (+)-beta-Pinen

Struktur von (−)-alpha-Pinen

Autor/Urheber: LIGURIAN VASCULAR FLORA, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

LOCATION

Eastern slopes of Bric Mergazze (Municipality of Varazze, Province of Savona, Liguria, IT). Latitude (WGS84): 44.3860 N. Longitude (WFS84): 8.6176 E. Elevation: 122 m (400 ft) Date: June 24, 2022. --- TAXONOMICAL INFORMATIONS Familia: Myrtaceae Juss. Species: Myrtus communis L. Subspecies: Myrtus communis L. subsp. communis First publication references: Sp. Pl.: 471 (1753). Synonyms: Myrtus acuta Mill.; Myrtus acutifolia (L.) Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus angustifolia Raf.; Myrtus baetica (L.) Mill.; Myrtus baui Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus belgica (L.) Mill.; Myrtus borbonis Sennen; Myrtus briquetii (Sennen & Teodoro) Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus buxifolia Raf.; Myrtus christinae (Sennen & Teodoro) Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus eusebii (Sennen & Teodoro) Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus gervasii; (Sennen & Teodoro) Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus italica Mill.; Myrtus josephi Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus lanceolata Raf.; Myrtus latifolia Raf.; Myrtus littoralis Salisb.; Myrtus macrophylla J. St.-Hil.; Myrtus major Garsault; Myrtus media Hoffmanns.; Myrtus microphylla J. St.-Hil.; Myrtus minima Mill.; Myrtus minor Garsault, des. inval.; Myrtus mirifolia Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus oerstedeana O.Berg; Myrtus petri-ludovici (Sennen & Teodoro) Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus rodesi Sennen & Teodoro; Myrtus romana (L.) Hoffmanns.; Myrtus romanifolia J. St.-Hil.; Myrtus sparsifolia O.Berg; Myrtus theodori Sennen; Myrtus veneris Bubani; Myrtus vidalii (Sennen & Teodoro) Sennen & Teodoro --- MORPHOLOGY AND FENOLOGY Life-form: phanerophyte. Description (M.S. Campbell, 1980): erect, much-branched shrub, up to 5 m. Twigs glandular-hairy when young. Leaves up to 5 cm, ovate-lanceolate, acute, entire, coriaceous, punctate, very aromatic when crushed. Flowers up to 3 cm in diameter, sweet-scented. Pedicels long, slender, with 2 small, caducous bracteoles. Petals suborbicular, white. Berry 7-10 x 6-8 mm, broadly ellipsoid to subglobose, usually blue-black when ripe. Flowering: from June to July but can bloom again in autumn. --- ECOLOGY AND CHOROLOGY Habitat: Mediterranean maquis, usually calcifuge. Vegetation belts: thermomediterranean, mesomediterranean. Edaphic preferences: Ca/Si; Si; Ser. Chorotype: Paleosubtropical. Global distribution (POWO, 2022): native to Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Azores, Baleares, Canary Is., Corse, Cyprus, East Aegean Is., Eritrea, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Iran, Iraq, Italy, Lebanon-Syria, Libya, Madeira, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia, Turkey, Yemen, ex-Yugoslavia. Introduced into California, Cape Provinces, Cuba, Leeward Is., Louisiana, Puerto Rico, Texas, Windward Is. Italian distribution (F. Bartolucci & alii, 2018): native in Friuli Venezia Giulia, Liguria, Tuscany, Umbria, Marches, Latium, Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, Sardinia. Introduced into Lombardy. Recorded by mistake in Emilia Romagna. Notes: species with a large Mediterranean and Paleotropical (montane) range. In Liguria it is widespread, common and generally abundant along the coast (albeit with some distribution gaps) and on the hills closest to the littoral zone. It is absent in the valleys on the Po side. Regional protection: no. --- REFERENCES

- M.S. Campbell (1980) – M. communis L. In: T.G. Tutin, N.A.Burges, A.O. Chater, J.R. Edmondson, V.H. Heywood, D.M. Moore, D.H. Valentine, S.M. Walters & D.A. Webb (Eds.) Flora Europaea 2 (ed. 2). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p. 303-304

- POWO (2022) – Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ Retrieved 06 November 2022.

- F. Bartolucci, L. Peruzzi, G. Galasso, A. Albano, A. Alessandrini, N. M. G. Ardenghi, G. Astuti, G. Bacchetta, S. Ballelli, E. Banfi, G. Barberis, L. Bernardo, D. Bouvet, M. Bovio, L. Cecchi, R. Di Pietro, G. Domina, S. Fascetti, G. Fenu, F. Festi, B. Foggi, L. Gallo, G. Gottschlich, L. Gubellini, D. Iamonico, M. Iberite, P. Jiménez-Mejías, E. Lattanzi, D. Marchetti, E. Martinetto, R. R. Masin, P. Medagli, N. G. Passalacqua, S. Peccenini, R. Pennesi, B. Pierini, L. Poldini, F. Prosser, F. M. Raimondo, F. Roma-Marzio, L. Rosati, A. Santangelo, A. Scoppola, S. Scortegagna, A. Selvaggi, F. Selvi, A. Soldano, A. Stinca, R. P. Wagensommer, T. Wilhalm & F. Conti (2018) – An updated checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosystems – An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology, 10.1080/11263504.2017.1419996, 152, 2, (179-303), (2018).

(+)-cis-delta-Pinen; (+)-cis-δ-Pinen

Struktur von (+)-alpha-Pinen