Säulen der Schöpfung

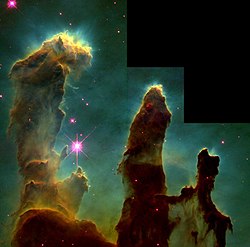

Säulen der Schöpfung ist der Name einer Formation, die mit dem Hubble-Weltraumteleskop im etwa 7000 Lichtjahre entfernten Adlernebel fotografiert wurde.[1] Das Bild wurde am 1. April 1995 aufgenommen, die verantwortlichen Astronomen waren Jeff Hester und Paul Scowen von der Arizona State University.

Informationen zum Bild

Das Gesamtbild wurde aus insgesamt 32 Einzelaufnahmen zusammengesetzt, die von vier separaten Kameras des Hubble-Teleskops aufgenommen wurden. Die Falschfarben auf dem Bild basieren auf der molekularen Zusammensetzung der Strukturen; so ist etwa Wasserstoff grün dargestellt, (einwertiger) Schwefel rot und (zweiwertiger) Sauerstoff blau.

In der oberen rechten Ecke des Bildes fehlt ein Stück der Aufnahme. Der Grund dafür ist, dass eine der vier Aufnahmekameras in einer anderen Auflösungsstufe als die übrigen drei arbeitete, um in ihrem Bildbereich kleinere Details sichtbar zu machen. Die zum Bildausschnitt gehörenden Aufnahmen von dieser Kamera wurden skaliert, um zu den übrigen Bildern zu passen.

Entstehung neuer Sterne

Die Säulen erstrecken sich vier Lichtjahre in den Weltraum und bestehen aus interstellarer Materie. Sie erodieren langsam durch Photoevaporation, dadurch werden an ihren Spitzen aus molekularem Wasserstoff und Staub bestehende Blasen (englisch: evaporating gas globule) freigelegt, in denen sich Protosterne bilden.[2]

Mögliche Zerstörung

Eine Forschergruppe um Nicolas Flagey vom Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale in Orsay bei Paris machte im Jahr 2007 mit dem Spitzer-Weltraumteleskop Infrarotaufnahmen von den Säulen der Schöpfung. Dabei wurde in der Region eine Wolke aus heißem Gas und Staub beobachtet, deren Ursache eine Supernova vor etwa 6000 Jahren gewesen sein könnte. Die Schockwelle dieser Supernova hat die Säulen der Schöpfung möglicherweise bereits zerstört, aufgrund der Entfernung von 7000 Lichtjahren wäre die Zerstörung jedoch erst in etwa 1000 Jahren auf der Erde zu sehen.[3][4]

Der Astrophysiker Stephen Reynolds von der North Carolina State University bezweifelt diese Interpretation. Laut Reynolds sollte bei einer Supernova eine wesentlich stärkere Abstrahlung von Radiowellen und Röntgenstrahlen beobachtet werden. In einem Interview mit New Scientist deutet Reynolds als alternative Erklärung eine Aufheizung des Staubes durch den Sternwind massiver Sterne an, die eine wesentlich langsamere Erosion der Formation bewirken würde.[5]

Herschel-Weltraumteleskop

2011 wurden die Säulen der Schöpfung durch das Herschel-Weltraumteleskop erneut beobachtet,[6] allerdings nur im fernen Infrarotbereich. Diese Aufnahmen führten zu einem wesentlich tiefergehenden Verständnis der Vorgänge im Adlernebel.

Erneute Beobachtungen

Anlässlich des 25. Geburtstags des Hubble-Teleskops veröffentlichten Astronomen im Januar 2015 ein wesentlich höher aufgelöstes Bild der Säulen der Schöpfung. Es wurde abermals vom Hubble-Teleskop, das zwischenzeitlich mit einer verbesserten Optik ausgestattet wurde, im sichtbaren und im kurzwelligen infraroten Bereich aufgenommen.[7]

Auch das JWST beobachtete im Jahr 2022 den Himmelsbereich der Säulen der Schöpfung.[8]

- Hochaufgelöste Aufnahme, die 2014 mit der zwischenzeitlich im Hubble-Weltraumteleskop installierten Kamera WFC3 in Anlehnung an das Original von 1995 gemacht wurde

- Aufnahme des JWST (2022)

- Aufnahme mithilfe des Mid Infrared Instrument des James-Webb-Weltraumteleskops

Namensgebung

Der Name beschreibt einerseits die säulenförmige Struktur und bezieht sich andererseits auf die Entstehung von Sternen innerhalb der Formation.

Weblinks

- Sternengeschichten Folge 634: Die Säulen der Schöpfung Podcast zum Blog „Astrodicticum Simplex“ von und mit Florian Freistetter.

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Whitney Clavin: 'Elephant Trunks' in Space ( des vom 25. Dezember 2018 im Internet Archive) Info: Der Archivlink wurde automatisch eingesetzt und noch nicht geprüft. Bitte prüfe Original- und Archivlink gemäß Anleitung und entferne dann diesen Hinweis., abgerufen am 26. November 2013.

- ↑ Embryonic Stars Emerge from Interstellar "Eggs". Website des HST Science Institute, abgerufen am 26. November 2013.

- ↑ Juliet Datson: „Säulen der Schöpfung“ vom Winde verweht? In: Sterne und Weltraum. 4, 2007. Artikel online

- ↑ Richard Lovett: Photo in the News: Supernova Destroys "Pillars of Creation". Abgerufen am 13. März 2011.

- ↑ David Shiga: 'Pillars of creation' destroyed by supernova. 10. Januar 2007, abgerufen am 26. November 2013.

- ↑ Revisiting the 'Pillars of Creation'. NASA, 18. Januar 2012, archiviert vom am 10. September 2019; abgerufen am 20. Januar 2012. Info: Der Archivlink wurde automatisch eingesetzt und noch nicht geprüft. Bitte prüfe Original- und Archivlink gemäß Anleitung und entferne dann diesen Hinweis.

- ↑ Hubble Goes High-Definition to Revisit Iconic 'Pillars of Creation'. NASA, 5. Januar 2015, abgerufen am 6. Januar 2015.

- ↑ Pillars of Creation (NIRCam Image). In: webbtelescope.org. 19. Oktober 2022, abgerufen am 19. Oktober 2022.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s mid-infrared view of the Pillars of Creation strikes a chilling tone. Thousands of stars that exist in this region disappear – and seemingly endless layers of gas and dust become the centerpiece.

The detection of dust by Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) is extremely important – dust is a major ingredient for star formation. Many stars are actively forming in these dense blue-gray pillars. When knots of gas and dust with sufficient mass form in these regions, they begin to collapse under their own gravitational attraction, slowly heat up – and eventually form new stars.

Although the stars appear missing, they aren’t. Stars typically do not emit much mid-infrared light. Instead, they are easiest to detect in ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared light. In this MIRI view, two types of stars can be identified. The stars at the end of the thick, dusty pillars have recently eroded the material surrounding them. They show up in red because their atmospheres are still enshrouded in cloaks of dust. In contrast, blue tones indicate stars that are older and have shed most of their gas and dust.

Mid-infrared light also details dense regions of gas and dust. The red region toward the top, which forms a delicate V shape, is where the dust is both diffuse and cooler. And although it may seem like the scene clears toward the bottom left of this view, the darkest gray areas are where densest and coolest regions of dust lie. Notice that there are many fewer stars and no background galaxies popping into view.

Webb’s mid-infrared data will help researchers determine exactly how much dust is in this region – and what it’s made of. These details will make models of the Pillars of Creation far more precise. Over time, we will begin to more clearly understand how stars form and burst out of these dusty clouds over millions of years.

Contrast this view with Webb’s near-infrared light image.

MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a consortium of nationally funded European Institutes (the MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with JPL and the University of Arizona. Credits:

SCIENCE: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

IMAGE PROCESSING: Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Alyssa Pagan (STScI)The Pillars of Creation are set off in a kaleidoscope of color in NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s near-infrared-light view. The pillars look like arches and spires rising out of a desert landscape, but are filled with semi-transparent gas and dust, and ever changing. This is a region where young stars are forming – or have barely burst from their dusty cocoons as they continue to form.

Newly formed stars are the scene-stealers in this Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) image. These are the bright red orbs that sometimes appear with eight diffraction spikes. When knots with sufficient mass form within the pillars, they begin to collapse under their own gravity, slowly heat up, and eventually begin shining brightly.

Along the edges of the pillars are wavy lines that look like lava. These are ejections from stars that are still forming. Young stars periodically shoot out supersonic jets that can interact within clouds of material, like these thick pillars of gas and dust. This sometimes also results in bow shocks, which can form wavy patterns like a boat does as it moves through water. These young stars are estimated to be only a few hundred thousand years old, and will continue to form for millions of years.

Although it may appear that near-infrared light has allowed Webb to “pierce through” the background to reveal great cosmic distances beyond the pillars, the interstellar medium stands in the way, like a drawn curtain.

This is also the reason why there are almost no distant galaxies in this view. This translucent layer of gas blocks our view of the deeper universe. Plus, dust is lit up by the collective light from the packed “party” of stars that have burst free from the pillars. It’s like standing in a well-lit room looking out a window – the interior light reflects on the pane, obscuring the scene outside and, in turn, illuminating the activity at the party inside.

Webb’s new view of the Pillars of Creation will help researchers revamp models of star formation. By identifying far more precise star populations, along with the quantities of gas and dust in the region, they will begin to build a clearer understanding of how stars form and burst out of these clouds over millions of years.

The Pillars of Creation is a small region within the vast Eagle Nebula, which lies 6,500 light-years away.

Webb’s NIRCam was built by a team at the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Technology Center.NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has revisited the famous Pillars of Creation, originally photographed in 1995, revealing a sharper and wider view of the structures in this visible-light image.

Astronomers combined several Hubble exposures to assemble the wider view. The towering pillars are about 5 light-years tall. The dark, finger-like feature at bottom right may be a smaller version of the giant pillars. The new image was taken with Hubble's versatile and sharp-eyed Wide Field Camera 3. The pillars are bathed in the blistering ultraviolet light from a grouping of young, massive stars located off the top of the image. Streamers of gas can be seen bleeding off the pillars as the intense radiation heats and evaporates it into space. Denser regions of the pillars are shadowing material beneath them from the powerful radiation. Stars are being born deep inside the pillars, which are made of cold hydrogen gas laced with dust. The pillars are part of a small region of the Eagle Nebula, a vast star-forming region 6,500 light-years from Earth.

The colors in the image highlight emission from several chemical elements. Oxygen emission is blue, sulfur is orange, and hydrogen and nitrogen are green.

A number of Herbig-Haro jets lengthened noticeably (see lower panel of linked page) in the nearly 20-year interval between the two Hubble images.

Object Names: M16, Eagle Nebula, NGC 6611.

A longer news release is linked here.

The original image was edited to reduce noise.

Star forming pillars in the Eagle Nebula, as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope's WFPC2. The picture is composed of 32 different images from four separate cameras in this instrument. The photograph was made with light emitted by different elements in the cloud and appears as a different colour in the composite image: green for hydrogen, red for singly-ionized sulphur and blue for double-ionized oxygen atoms. The missing part at the top right is because one of the four cameras has a magnified view of its portion, which allows astronomers to see finer detail. The images from this camera were scaled down in size to match those from the other three cameras. Further information at: Credit: NASA, Jeff Hester, and Paul Scowen (Arizona State University)