Phylogenetik

Die Phylogenetik (retronymes Kofferwort aus altgriechisch φυλή, φῦλονphylé, phylon, deutsch ‚Stamm‘, ‚Clan‘, ‚Sorte‘ und γενετικόςgenetikós, deutsch ‚Ursprung‘) ist eine Fachrichtung der Genetik und Bioinformatik, die sich mit der Erforschung von Abstammungen beschäftigt.

Eigenschaften

Die Phylogenetik verwendet heutzutage Algorithmen zur Bestimmung von Verwandtschaftsgraden zwischen verschiedenen Arten oder zwischen Individuen einer Art aus DNA-Sequenzen, die zuvor per DNA-Sequenzierung ermittelt wurden. Dadurch kann ein phylogenetischer Baum erstellt werden. Die Phylogenetik wird unter anderem zur Erzeugung von Taxonomien herangezogen. Als Algorithmen werden unter anderem Parsimony, die Maximum-Likelihood-Methode (ML-Methode) und die MCMC-basierte Bayesische Inferenz verwendet.[1][2] Vor der Entwicklung der DNA-Sequenzierung und von Computern wurde die Phylogenetik aus Phänotypen über eine Distanzmatrix abgeleitet (Phänetik),[3] jedoch waren die Unterscheidungskriterien teilweise nicht eindeutig, da Phänotypen – selbst über einen kurzen Zeitraum betrachtet – von vielen weiteren Faktoren beeinflusst werden und sich verändern.[4][5]

Geschichte

Im 14. Jahrhundert entwickelte der franziskanische Philosoph Wilhelm von Ockham das Abstammungsprinzip lex parsimoniae. Im Jahr 1763 wurde Pastor Thomas Bayes’ Grundlagenwerk zur Bayesschen Statistik veröffentlicht.[6] Im 18. Jahrhundert führte Pierre Simon Laplace, Marquis de Laplace, eine Form des Maximum-likelihood-Ansatzes ein. 1837 publizierte Charles Darwin die Evolutionstheorie mit einer Darstellung eines Stammbaums. Eine Unterscheidung der Homologie und der Analogie wurde erstmals 1843 von Richard Owen getroffen. Der Paläontologe Heinrich Georg Bronn publizierte 1858 erstmals das Aussterben und Neuauftreten von Arten im Stammbaum.[7] Im gleichen Jahr wurde die Evolutionstheorie erweitert.[8] Die Bezeichnung Phylogenie wurde 1866 von Ernst Haeckel geprägt.[9] Er postulierte in seiner Rekapitulations-Theorie einen Zusammenhang zwischen der Phylogenese und der Ontogenese, der heute nicht mehr haltbar ist.[10][11] Im Jahr 1893 wurde Dollo’s Law of Character State Irreversibility veröffentlicht.[12]

Im Jahr 1912 verwendete Ronald Fisher die maximum likelihood (Maximum-Likelihood-Methode in der molekularen Phylogenie). 1921 wurde die Bezeichnung phylogenetisch von Robert John Tillyard bei seiner Klassifizierung geprägt.[13] Im Jahr 1940 führte Lucien Cuénot den Begriff der Klade ein. Ab 1946 präzisierten Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, ab 1949 Maurice Quenouille und ab 1958 John Tukey das Vorläufer-Konzept.

Im Jahr 1950 folgte eine erste Zusammenfassung von Willi Hennig,[14] im Jahr 1966 die englische Übersetzung.[15] 1952 entwickelte William Wagner die Divergenzmethode.[16] 1953 wurde der Begriff Kladogenese geprägt.[17] Arthur Cain und Gordon Harrison verwendeten ab 1960 die Bezeichnung kladistisch.[18] Ab 1963 verwendeten A. W. F. Edwards und Cavalli-Sforza die maximum likelihood in der Linguistik.[19] Im Jahr 1965 wurde von J. H. Camin und Robert R. Sokal die Camin-Sokal parsimony und ein erstes Computerprogramm für kladistische Analysen entwickelt.[20] Im gleichen Jahr wurde die character compatibility method gleichzeitig von Edward Osborne Wilson sowie von Camin und Sokal entwickelt.[21] Im Jahr 1966 wurden die Begriffe Kladistik und Kladogramm geprägt. 1969 entwickelte James Farris die dynamische und sukzessive Wichtung,[22] auch erschien die Wagner parsimony von Kluge und Farris[23] und der CI (consistency index).[23] sowie die paarweise Kompatibilität der Clique-Analyse von W. Le Quesne.[24] Im Jahr 1970 generalisierte Farris die Wagner parsimony.[25] 1971 veröffentlichte Walter Fitch die Fitch parsimony[26] und David F. Robinson veröffentlichte den NNI (nearest neighbour interchange),[27] zeitgleich mit Moore u. a. Auch wurde 1971 die ME (minimum evolution) von Kidd und Sgaramella-Zonta publiziert.[28] Im folgenden Jahr entwickelte E. Adams den Adams consensus.[29]

Die erste Anwendung des maximum likelihood für Nukleinsäuresequenzen erfolgte 1974 durch J. Neyman.[30] Farris publizierte 1976 das Präfix-System für Ränge.[31] Ein Jahr später entwickelte er die Dollo parsimony.[32] Im Jahr 1979 wurde der Nelson consensus von Gareth Nelson veröffentlicht,[33] sowie der MAST (maximum agreement subtree) und GAS (greatest agreement subtree) von A. Gordon[34] und der bootstrap von Bradley Efron.[35] 1980 wurde PHYLIP als erste Software für phylogenetische Analysen von Joseph Felsenstein publiziert. Im Jahr 1981 wurde der majority consensus von Margush und MacMorris,[36] der strict consensus von Sokal und Rohlf[37] und der erste effiziente Maximum-Likelihood-Algorithmus von Felsenstein.[38] Im folgenden Jahr wurden PHYSIS von Mikevich und Farris sowie branch and bound. von Hendy und Penny[39] veröffentlicht. 1985 wurde, basierend auf Genotyp und Phänotyp, die erste kladistische Analyse von Eukaryoten durch Diana Lipscomb publiziert.[40] Im gleichen Jahr wurde bootstrap erstmals für phylogenetische Untersuchungen von Felsenstein verwendet,[41] ebenso wie jackknife von Scott Lanyon.[42] 1987 wurde die neighbor-joining method von Saitou und Nei publiziert.[43] Im Jahr darauf wurde Hennig86 in der Version 1.5 von Farris entwickelt. Im Jahr 1989 wurde der RI (retention index) und der RCI (rescaled consistency index) von Farris[44] und die HER (homoplasy excess ratio) von Archie publiziert.[45] 1990 wurde der combinable components (semi-strict) consensus von Bremer[46] sowie das SPR (subtree pruning and regrafting) und die TBR (tree bisection and reconnection) von Swofford und Olsen veröffentlicht.[47] Im Jahr 1991 folgte der DDI (data decisiveness index) von Goloboff.[48][49] 1993 wurde das implied weighting von Goloboff publiziert.[50] Im Jahr 1994 wurde der decay index von Bremer veröffentlicht.[51] Ab 1994 wurde der reduced cladistic consensus von Mark Wilkinson entwickelt.[52][53] 1996 wurde die erste MCMC-basierte Anwendung der Bayesschen Inferenz unabhängig von Li,[54] Mau[55] sowie Rannalla und Yang entwickelt.[56] Im Jahr 1998 wurde die TNT (Tree Analysis Using New Technology) von Goloboff, Farris und Nixon publiziert. 2003 wurde das symmetrical resampling von Goloboff veröffentlicht.[57]

Anwendungen

Evolution von Karzinomen

Seit der Entwicklung von Next Generation Sequencing kann man die Evolution von Krebszellen auch auf molekularer Ebene verfolgen.[58] Wie im Hauptartikel Karzinogenese beschrieben, entsteht ein Tumor zuerst durch eine Mutation in einer Zelle. Unter bestimmten Bedingungen häufen sich weitere Mutationen an, die Zelle teilt sich unbeschränkt und schränkt ihre DNA-Reparatur weiter ein. Es entwickelt sich ein Tumor, der aus verschiedenen Zellpopulationen besteht, die jeweils unterschiedliche Mutationen haben können. Diese Tumor-Heterogenität ist gerade für die Behandlung von Krebspatienten von enormer Bedeutung. Phylogenetische Methoden[59][60] erlauben es, den Stammbaum für einen Tumor zu bestimmen. An diesem kann man ablesen, welche Mutationen in welcher Subpopulation des Tumors vorhanden sind.

Linguistik

Cavalli-Sforza beschrieb erstmals die Ähnlichkeit der Phylogenetik von Genen mit der Evolution von Sprachen aus Ursprachen.[61][62] Die Methoden der Phylogenetik werden daher auch zur Bestimmung von Abstammungen von Sprachen verwendet.[63] Dies führte unter anderem dazu, die sogenannte Urheimat der indoeuropäischen Sprachfamilie in Anatolien zu verorten.[64] In der Wissenschaft ist diese Anwendungsübertragung der Phylogenetik jedoch grundsätzlich umstritten, da die Verbreitung von Sprachen nicht nach biologisch-evolutionären Mustern verläuft, sondern eigenen Gesetzmäßigkeiten folgt.[65]

Literatur

- David Williams: The Future of Phylogenetic Systematics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2016, ISBN 978-1-316-68918-9.

- Donald R. Forsdyke: Evolutionary Bioinformatics. 3. Auflage. Springer, Cham 2016, ISBN 978-3-319-28755-3.

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Charles Semple: Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-850942-1.

- ↑ David Penny: Inferring Phylogenies.—Joseph Felsenstein. 2003. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts. In: Systematic Biology. Band 53, Nr. 4, 1. August 2004, ISSN 1063-5157, S. 669–670, doi:10.1080/10635150490468530 (englisch, oup.com [abgerufen am 13. März 2020]).

- ↑ A. W. F. Edwards, L. L. Cavalli-Sforza: Reconstruction of evolutionary trees (PDF) In: Vernon Hilton Heywood, J. McNeill: Phenetic and Phylogenetic Classification. Systematics Association, 1964, S. 67–76.

- ↑ Masatoshi Nei: Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-19-513585-7, S. 3.

- ↑ E. O. Wiley: Phylogenetics. John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 978-1-118-01787-6.

- ↑ T. Bayes: An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances. In: Phil. Trans. 53, 1763, S. 370–418.

- ↑ J. David Archibald: Edward Hitchcock’s Pre-Darwinian (1840) 'Tree of Life'. In: Journal of the History of Biology. 2009, S. 568.

- ↑ Charles R. Darwin, A. R. Wallace: On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection. Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. In: Zoology. Band 3, 1858, S. 45–50.

- ↑ Douglas Harper: Phylogeny. In: Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Erich Blechschmidt: The Beginnings of Human Life. Springer-Verlag, 1977, S. 32.

- ↑ Paul Ehrlich, Richard Holm, Dennis Parnell: The Process of Evolution. McGraw–Hill, New York 1963, S. 66.

- ↑ Louis Dollo: Les lois de l’évolution. In: Bull. Soc. Belge Géol. Paléont. Hydrol. Band 7, 1893, S. 164–166.

- ↑ Robert J. Tillyard: A new classification of the order Perlaria. In: Canadian Entomologist. Band 53, 1921, S. 35–43.

- ↑ W. Hennig: Grundzüge einer Theorie der phylogenetischen Systematik. Deutscher Zentralverlag, Berlin 1950.

- ↑ W. Hennig: Phylogenetic systematics. Illinois University Press, Urbana 1966.

- ↑ W. H. Wagner Jr.: The fern genus Diellia: structure, affinities, and taxonomy. In: Univ. Calif. Publ. Botany. Band 26, 1952, S. 1–212.

- ↑ Webster’s 9th New Collegiate Dictionary

- ↑ A. J. Cain, G. A. Harrison: Phyletic weighting. In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Band 35, 1960, S. 1–31.

- ↑ A. W. F. Edwards, L. L. Cavalli-Sforza: The reconstruction of evolution. In: Ann. Hum. Genet. Band 27, 1963, S. 105–106.

- ↑ J. H. Camin, R. R. Sokal: A method for deducing branching sequences in phylogeny. In: Evolution. Band 19, 1965, S. 311–326.

- ↑ E. O. Wilson: A consistency test for phylogenies based on contemporaneous species. In: Systematic Zoology. Band 14, 1965, S. 214–220.

- ↑ J. S. Farris: A successive approximations approach to character weighting. In: Syst. Zool. Band 18, 1969, S. 374–385.

- ↑ a b A. G. Kluge, J. S. Farris: Quantitative phyletics and the evolution of anurans. In: Syst. Zool. Band 18, 1969, S. 1–32.

- ↑ W. J. Le Quesne: A method of selection of characters in numerical taxonomy. In: Systematic Zoology. Band 18, 1969, S. 201–205.

- ↑ J. S. Farris: Methods of computing Wagner trees. In: Syst. Zool. Band 19, 1970, S. 83–92.

- ↑ W. M. Fitch: Toward defining the course of evolution: minimum change for a specified tree topology. In: Syst. Zool. Band 20, 1971, S. 406–416.

- ↑ D. F. Robinson: Comparison of labeled trees with valency three. In: Journal of Combinatorial Theory. Band 11, 1971, S. 105–119.

- ↑ K. K. Kidd, Laura Sgaramella-Zonta: Phylogenetic analysis: concepts and methods. In: Am. J. Human Genet. Band 23, 1971, S. 235–252.

- ↑ E. Adams: Consensus techniques and the comparison of taxonomic trees. In: Syst. Zool. Band 21, 1972, S. 390–397.

- ↑ J. Neyman: Molecular studies: A source of novel statistical problems. In: S. S. Gupta, J. Yackel: Statistical Decision Theory and Related Topics. Academic Press, New York 1974, S. 1–27.

- ↑ J. S. Farris: Phylogenetic classification of fossils with recent species. In: Syst. Zool. Band 25, 1976, S. 271–282.

- ↑ J. S. Farris: Phylogenetic analysis under Dollo’s Law. In: Syst. Zool. 26, 1977, S. 77–88.

- ↑ Gareth J. Nelson: Cladistic Analysis and Synthesis: Principles and Definitions, with a Historical Note on Adanson’s Familles Des Plantes (1763–1764). In: Syst. Zool. Band 28, 1979, S. 1–21. doi:10.1093/sysbio/28.1.1

- ↑ A. D. Gordon: A measure of the agreement between rankings. In: Biometrika. Band 66, 1979, S. 7–15. doi:10.1093/biomet/66.1.7

- ↑ B. Efron: Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. In: Ann. Stat. 7, 1979, S. 1–26.

- ↑ T. Margush, F. R. McMorris: Consensus n-trees. In: Bull. Math. Biol. Band 43, 1981, S. 239–244.

- ↑ R. R. Sokal, F. J. Rohlf: Taxonomic congruence in the Leptopodomorpha re-examined. In: Syst. Zool. 30, 1981, S. 309–325.

- ↑ J. Felsenstein: Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. In: J. Mol. Evol. 17, 1981, S. 368–376.

- ↑ M. D. Hendy, D. Penny: Branch and bound algorithms to determine minimal evolutionary trees. In: Math Biosci. 59, 1982, S. 277–290.

- ↑ Diana Lipscomb: The Eukaryotic Kingdoms. In: Cladistics. 1, 1985, S. 127–140.

- ↑ J. Felsenstein: Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. In: Evolution. 39, 1985, S. 783–791.

- ↑ S. M. Lanyon: Detecting internal inconsistencies in distance data. In: Syst. Zool. 34, 1985, S. 397–403.

- ↑ N. Saitou, M. Nei: The Neighbor-joining Method: A New Method for Constructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol. Biol. In: Evol. 4, 1987, S. 406–425.

- ↑ J. S. Farris: The retention index and rescaled consistency index. In: Cladistics. Band 5, 1989, S. 417–419.

- ↑ J. W. Archie: Homoplasy Excess Ratios: new indices for measuring levels of homoplasy in phylogenetic systematics and a critique of the Consistency Index. In: Syst. Zool. Band 38, 1989, S. 253–269.

- ↑ Kåre Bremer: Combinable Component Consensus. In: Cladistics. Band 6, 1990, S. 369–372.

- ↑ D. L. Swofford, G. J. Olsen: Phylogeny reconstruction. In: D. M. Hillis, G. Moritz: Molecular Systematics. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass., 1990, S. 411–501.

- ↑ P. A. Goloboff: Homoplasy and the choice among cladograms. In: Cladistics. Band 7, 1991, S. 215–232.

- ↑ P. A. Goloboff: Random data, homoplasy and information. In: Cladistics. Band 7, 1991, S. 395–406.

- ↑ P. A. Goloboff: Estimating character weights during tree search. In: Cladistics. 9, 1993, S. 83–91.

- ↑ K. Bremer: Branch support and tree stability. In: Cladistics. 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1994.tb00179.x

- ↑ Mark Wilkinson: Common cladistic information and its consensus representation: reduced Adams and reduced cladistic consensus trees and profiles. In: Syst. Biol. Band 43, 1994, S. 343–368.

- ↑ Mark Wilkinson: More on reduced consensus methods. In: Syst. Biol. Band 44, 1995, S. 436–440.

- ↑ S. Li: Phylogenetic tree construction using Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University, Columbus 1996.

- ↑ B. Mau: Bayesian phylogenetic inference via Markov chain Monte Carlo Methods. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison 1996. (abstract)

- ↑ B. Rannala, Z. Yang: Probability distribution of molecular evolutionary trees: A new method of phylogenetic inference. In: J. Mol. Evol. 43, 1996, S. 304–311.

- ↑ Pablo Goloboff, James Farris, Mari Källersjö, Bengt Oxelman, Maria Ramiacuterez, Claudia Szumik: Improvements to resampling measures of group support. In: Cladistics. 19, 2003, S. 324–332.

- ↑ Niko Beerenwinkel, Chris D. Greenman, Jens Lagergren: Computational Cancer Biology: An Evolutionary Perspective. In: PLoS Computational Biology. Band 12, Nr. 2, 4. Februar 2016, ISSN 1553-734X, doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004717, PMID 26845763, PMC 4742235 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Niko Beerenwinkel, Chris D. Greenman, Jens Lagergren: Computational Cancer Biology: An Evolutionary Perspective. In: PLoS Computational Biology. Band 12, Nr. 2, 4. Februar 2016, ISSN 1553-734X, doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004717, PMID 26845763, PMC 4742235 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Niko Beerenwinkel, Roland F. Schwarz, Moritz Gerstung, Florian Markowetz: Cancer Evolution: Mathematical Models and Computational Inference. In: Systematic Biology. Band 64, Nr. 1, 1. Januar 2015, ISSN 1063-5157, S. e1–e25, doi:10.1093/sysbio/syu081 (englisch).

- ↑ L. L. Cavalli-Sforza: An Evolutionary View in Linguistics. In: M. Y. Chen, O. J.-L. Tzeng: Interdisciplinary Studies on Language and Language Change. Pyramid, Taipei 1994, S. 17–28.

- ↑ L. L. Cavalli-Sforza, William S.-Y. Wang: Spatial Distance and Lexical Replacement. In: Language. Band 62, 1986, S. 38–55.

- ↑ Remco Bouckaert, Philippe Lemey, Michael Dunn, Simon J. Greenhill, Alexander V. Alekseyenko: Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family. In: Science. Band 337, Nr. 6097, 24. August 2012, ISSN 0036-8075, S. 957–960, doi:10.1126/science.1219669, PMID 22923579 (englisch).

- ↑ Remco Bouckaert, Philippe Lemey, Michael Dunn, Simon J. Greenhill, Alexander V. Alekseyenko: Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family. In: Science. Band 337, Nr. 6097, 24. August 2012, ISSN 0036-8075, S. 957–960, doi:10.1126/science.1219669, PMID 22923579, PMC 4112997 (freier Volltext) – (englisch, sciencemag.org [abgerufen am 29. März 2020]).

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W., Pereltsvaig, Asya: The Indo-European Controversy: Facts and Fallacies in Historical Linguistics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (United Kingdom) 2015, ISBN 978-1-316-31924-6, doi:10.1017/CBO9781107294332 (englisch).

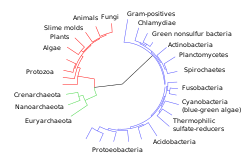

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Branching tree diagram from Heinrich Georg Bronn's work, "Untersuchungen über die Entwicklungs-Gesetze der organischen Welt während der Bildungszeit unserer Erd-Oberfläche" (1858).

Vereinfachte Version eines hochaufgelösten Stammbaums (Kladogramm) der gesamten Organismenwelt („Tree of Life“), basierend auf komplett sequenzierten Genomen[1]. Die detaillierte (terminale Taxa auf Art-Ebene) ursprüngliche Abbildung wurde erzeugt mittels iTOL: Interactive Tree Of Life[2], eines/einer Online-Viewers/Online-Ressource für derartige Stammbäume. Von dieser Grafik wurde eine vereinfachte Version in Form einer PNG-Datei erstellt, die wiederum für die Erstellung der SVG-Version händisch abgezeichnet wurde. Die Eukaryoten-Klade ist in Rot dargestellt, die Archeen-Klade in Grün und die Bakterien-Klade in Blau.