New General Catalogue

Der New General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars (NGC) ist ein Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts entstandener Katalog von galaktischen Nebeln, Sternhaufen und Galaxien, der noch heute als Standardwerk gilt. Er wurde in den 1880er-Jahren zusammengestellt und 1888 von Johan Ludvig Emil Dreyer veröffentlicht; eine wichtige Grundlage waren die systematischen Himmelsdurchmusterungen und speziellen Beobachtungen von Wilhelm Herschel. 1895 und 1908 wurde der NGC um die beiden Index-Kataloge IC I und IC II erweitert. Der NGC enthält 7840 Einträge, darunter auch die meisten des Messier-Katalogs. Im Unterschied zu diesem sind die Objekte des NGC-Katalogs nach Rektaszension geordnet. Er enthält Objekte des Nord- und des Südhimmels. Der Katalog enthält jedoch einzelne Fehler – z. B. sind einige Objekte mehrmals unter verschiedenen Katalognummern enthalten oder wurden nochmals in einen der Index-Kataloge aufgenommen. Der Versuch, diese Fehler zu beseitigen, wurde 1993 durch das NGC/IC-Projekt initiiert, nach teilweisen Versuchen mit dem Revised New General Catalogue (RNGC) von Jack W. Sulentic und William G. Tifft im Jahr 1973 und NGC2000.0 von Roger W. Sinnott im Jahr 1988. Eine vollständige Überarbeitung des NGC und der zugehörigen Indexkataloge wurde von Wolfgang Steinicke 2009 erstellt.

Der NGC wird gerne von Amateurastronomen verwendet, weil er viele Objekte enthält, die auch mit Amateurteleskopen noch beobachtet werden können.

Vorläuferkataloge

Einige wenige „neblige“ Flecken und Sternansammlungen am Himmel waren bereits seit der Antike bekannt, wie die Plejaden und χ Persei, oder seit dem Mittelalter, wie der Andromedanebel. Durch das Verwenden von Teleskopen für die Himmelsbeobachtung konnten immer mehr Details des Sternhimmels erkannt werden, die für das bloße Auge unsichtbar blieben. Einige Nebel konnten durch die Verbesserung der Technik und Verwendung von größeren Teleskopen aufgelöst werden, wie z. B. Kugelsternhaufen. Andere Objekte wie z. B. der Orionnebel oder der Andromedanebel konnten nicht in Sterne aufgelöst werden. Astronomen versuchten, die nebeligen Flecken zu katalogisieren, wie z. B. Messier, der sich eine Liste von Objekten zusammenstellte, um diese von Kometen zu unterscheiden. Mit ihren immer besseren Teleskopen erstellten Astronomen wie Wilhelm Herschel, John Herschel, William Parsons eigene Kataloge, um ihre Entdeckungen zu dokumentieren.

Wilhelm Herschel, der berühmte Entdecker des Planeten Uranus, begann Ende Oktober 1783, den Himmel mit einem selbstgebauten 18,7-Zoll-Reflektor systematisch nach nichtstellaren Objekten abzusuchen.[1] Der Catalogue of Nebulae and Cluster of Stars (CN) wurde erstmals 1786 von Wilhelm Herschel in den Philosophical Transactions der Royal Society of London veröffentlicht. 1789 fügte er weitere 1.000 Einträge hinzu und schließlich 1802 weitere 500. Damit erhöhte sich die Gesamtzahl auf 2.500. Seine Schwester Caroline Herschel entdeckte weitere 10 Objekte.[1] Um ihre Eindrücke über die Helligkeit und Struktur eines Objekts festzuhalten, waren damals Texte und Skizzen die einzigen Medien. Diese Aufzeichnungen waren sehr subjektiv und abhängig vom jeweiligen Talent und Erfahrung des Beobachters. Um die Aufzeichnungen zu objektivieren, entwickelte Wilhelm Herschel eine standardisierte Beschreibung.[2] Die Kataloge von Wilhelm Herschel hatten zwei große Nachteile: Sie wurden nach dem Datum der Entdeckung geordnet. Zudem wurde die Position eines Objekts nur relativ zu einem Referenzstern angegeben, es gab also keine Koordinaten. Dies erschwerte die Identifizierung eines Objekts sehr, insbesondere von neu entdeckten.[2]

John Herschel führte die Arbeit seines Vaters fort. In seinem Observatorium in Slough erstellte er zwischen 1825 und 1833 den Slough Catalogue (SC).[3] Für seine Beobachtungen benutzte er einen Reflektor mit einer Öffnung von 18¼″ (ca. 46 cm), der 1820 fertiggestellt wurde. Seine Absicht war nicht so sehr die Entdeckung neuer Nebel und Sternhaufen, sondern vielmehr wollte er die drei Kataloge seines Vaters erneut überprüfen. Die Hauptziele waren die Identifizierung und Bestimmung der genauen Positionen.[2]

Im Jahr 1834 zogen John Herschel und seine Familie nach Kapstadt. Er erwarb das Gut Feldhausen, wo er in den nächsten vier Jahren eine ähnliche Vermessung des Südhimmels durchführte. Dort, am Kap der Guten Hoffnung, beobachtete er in den Jahren 1834 bis 1838 insgesamt 1714 Objekte.[1]

1864 wurde der CN von John Herschel zum General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars (GC) erweitert.

| Autor | Katalog | Abkürzung | Datum | Anzahl Einträge | Anzahl neuer Einträge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charles Messier | Messier-Katalog | M | 1781 | 103 | 103 |

| Wilhelm Herschel | Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars (drei Kataloge) | CN (H) | 1786, 1789, 1802 | 2500 | 2427 |

| John Herschel | Slough-Katalog | SC (h) | 1833 | 2307 | 473 |

| John Herschel | Cape-Katalog | CC (h) | 1847 | 1714 | 1421 |

| William Parsons | Birr Castle | LdR | 1861 | 989 | 295 |

| Auwers | List of new nebulae | Au | 1862 | 50 | 46 |

| John Herschel | General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters | GC | 1864 | 5057 | 419 |

| d’Arrest | Siderum Nebulosorum | SN | 1867 | 1942 | 307 |

| Dreyer | GC Supplement | GCS | 1878 | 1166 | 1149 |

| Lawrence Parsons | Observations of nebulae and clusters of stars made with the six-foot and three-foot reflectors at Birr Castle | 1880 | 1840 | 94 | |

| Dreyer | New General Catalogue | NGC | 1888 | 7840 | 1700 |

| Dreyer | Index Catalogue I | IC | 1895 | 1529 | |

| Dreyer | Index Catalogue II | IC | 1908 | 3857 |

Der New General Catalogue

Johan Dreyer

Johan Dreyer wurde am 13. Februar 1852 in Kopenhagen geboren.[1] Er stammte aus einer traditionsreichen Familie mit engen Beziehungen zum Militär.[1] Er begann im Alter von 17 Jahren in Kopenhagen Mathematik und Astronomie zu studieren. Hier hörte er auch Vorlesungen von d’Arrest.[1] Nachdem er sein Studium abgeschlossen hatte, zog er im August 1874 ins irische Parsonstown (heute Birr). Dort wurde er Assistent von Lawrence Parsons und hatte Zugang zum damals weltgrößten Teleskop, dem Leviathan.[1] Vier Jahre lang konnte er diesen 72-Zoll-Reflektor und den 36-Zoll-Reflektor benutzen. Seine Beobachtungen dort betrafen hauptsächlich Nebel und Sternhaufen.[4]

1882 wurde Dreyer Direktor des Armagh-Observatoriums. Seine erste Arbeit war hier die Fertigstellung des Second Armagh Catalogue of Stars seines Vorgängers. Während seiner Jahre in Armagh benutzte Dreyer dessen Ausstattung zum Messen von Nebeln, Sternen, Kometen, Doppelsternen und weiteren astronomischen Beobachtungen.[4]

Erstellung und Veröffentlichung des Katalogs

Diskrepanzen zwischen dem General Catalogue von John Herschel und der Entdeckung weiterer Nebel führten Dreyer dazu, eine eigene Erweiterung für seine eigenen Beobachtungen zu erstellen.[4] Er war daran interessiert, sich ein vollständiges Bild über die aktuellen Beobachtungen von bekannten oder neuen Objekten zu machen. Er nahm an, dass nicht alle Daten tatsächlich veröffentlicht wurden. Deshalb schrieb er am 11. November 1876 ein Request to astronomers, das eine Woche später in den Astronomischen Nachrichten erschien. Dieses Ersuchen enthielt die Bitte, an ihn noch unveröffentlichte Daten oder Informationen zu Fehlern im General Catalogue zu schicken.[2] Die Ergebnisse, die d’Arrest im Katalog Siderum Nebulosorum veröffentlichte, wollte er mit in eine Erweiterung des General Catalogue aufnehmen.[2] Die von ihm erstellte Erweiterung General Catalogue Supplement (GCS) wurde 1878 in The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy veröffentlicht.[4] Es enthielt alle bekannten Korrekturen zum General Catalogue und fügte zu Herschels 5079 Nebeln weitere 1172 hinzu.[4] Während der Erweiterung des General Catalogues arbeitete Dreyer zugleich an der Zusammenstellung der Beobachtungsergebnisse am Birr Castle, die Lawrence Parson und seine Assistenten gemacht haben, aus den Jahren 1848–1878.[2] Das Werk enthält einige seiner Skizzen. Im GCS wurden alle gefundenen 90 Objekte dieser Beobachtungen aufgenommen.[2] Lawrence Parsons veröffentlichte das Ergebnis in drei Teilen in der Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society im Jahr 1880.[2]

Dreyer verfolgte nach der Herausgabe des GCS die weiteren Veröffentlichungen anderer Astronomen. Weitere Veröffentlichungen von Beobachtungen von Nebeln und Sternhaufen von Lord Rosse zwischen 1848 und 1878 zusammen mit Beobachtungen anderer Astronomen führten Dreyer dazu, eine zweite Ergänzung vorzubereiten.[4] Er schrieb eine Mitteilung, dass er Materialien für einen zweiten Ergänzungskatalog sammle. Diese Mitteilung Notice of a new catalogue of nebulae wurde in den Astronomischen Nachrichten 1885 veröffentlicht.[5] Hier bat er wiederum um die Zusendung unveröffentlichter Entdeckungen.[2] Der Vorstand der Royal Astronomical Society lehnte jedoch diese Ergänzung überraschenderweise ab. Sie bat ihn, alle drei Kataloge zu einem zusammenzuführen. Innerhalb von nur zwei Jahren stellte Dreyer diesen neuen Katalog zusammen. Zu seinem Bedauern war es erforderlich, eine neue Nummerierung der Einträge vorzunehmen, die heutigen NGC-Nummern.[6] Dieser New General Catalogue wurde im Jahr 1888 als Memoir of the Royal Astronomical Society veröffentlicht.[4]

Nahezu 78 % der Einträge des NGC sind bereits in Herschels General Catalogue vorhanden.[4] Nur 20 Beobachtungen sind direkt Dreyer zuzuschreiben.[4] 4000 Beobachtungen wurden von anderen Beobachtern gemacht.[4] Dreyers großer Beitrag lag darin, die Ergebnisse der einzelnen Beobachter rigoros miteinander zu vergleichen und zu prüfen, um einen möglichst exakten Katalog zu haben.[4] Er veröffentlichte den NGC mit 7840 Einträgen im Jahr 1888. Dieser letzte visuell zusammengetragene Katalog umfasst 7586 unabhängige Objekte. Nur ein Objekt des Katalogs wurde fotografisch entdeckt.[1]

Aufbau

Dreyer orientierte sich beim Aufbau des Katalogs an den Katalogen von John Herschel.[6]

- "No.": Fortlaufende Nummer im NGC

- "G.C.": Nummer im "General Catalogue" von John Herschel (1–5079) oder der ersten Erweiterung von Dreyer (5080–6251)

- "J.H.": Nummer der Slough-Beobachtungen von John Herschel und dessen Beobachtungen vom Kap der Guten Hoffnung

- "W.H.": Klassifikation und Nummer von Wilhelm Herschel aus den Beobachtungen von 1786, 1789, 1802

- "Other Observers": Weitere Beobachter des Objekts. Häufig auftretende Namen wurden von Dreyer abgekürzt, z. B.: "d’A" für d’Arrest, "Auw." für Auwers.

- "Right Ascension, 1860": Rektaszension für die Epoche 1860

- "Annual Precession, 1880": Jährliche Präzession der Rektaszension im Jahre 1880

- "North Polar Distance 1860": Entfernung vom Nordpol in Winkelgrad für die Epoche 1860

- "Annual Precession, 1880": Jährliche Präzession der Nord-Polar-Distanz im Jahre 1880

- "Summary Description": In dieser Spalte werden in Kurzform die wesentlichen Eigenschaften des Objekts angegeben (Helligkeit, Größe, Form, besondere Merkmale)

Statistik

Von den 7840 Einträgen im NGC-Katalog haben 238 Objekte zwei Einträge. 16 Mal tritt ein Objekt dreimal auf. Insgesamt gibt es 7586 unabhängige Einträge. Am häufigsten sind Galaxien im Katalog vertreten (79,5 %), gefolgt von offenen Sternhaufen (9 %) und Emissions- und Reflexionsnebeln (2 %), Kugelsternhaufen (1,5 %) und planetarischen Nebeln (1,2 %). Insgesamt 5,2 % sind Einzelsterne oder Sterngruppen, 0,4 % betreffen Teile von anderen Galaxien, dies sind meist HII-Regionen.[1]

Die scheinbare Helligkeit der Objekte beträgt im Mittel 12,6 mag, das Minimum liegt bei 16,4 mag.[2]

Entdecker

Zum NGC trugen genau 100 Entdecker bei. 26 davon entfallen auf die Zeit vor Wilhelm Herschel (1783).[1]

- Wilhelm Herschel: 2416

- John Herschel: 1691

- Albert Marth: 582

- Lewis A. Swift: 466

- Édouard Jean-Marie Stephan: 420

- Heinrich Louis d’Arrest: 320

- Francis Preserved Leavenworth: 251

- James Dunlop: 225

- Ernst Wilhelm Leberecht Tempel: 148

- andere Beobachter: 1067

Eine detaillierte Liste findet sich unter Liste der Entdecker des NGC/IC-Katalogs.

Insgesamt waren 71 Teleskope an den Entdeckungen beteiligt, 11 davon waren Reflektoren mit Spiegeldurchmessern zwischen 4,2 Zoll und 72 Zoll, 60 waren Refraktoren mit Öffnungen zwischen 3 und 27 Zoll.

7814 Einträge wurden visuell entdeckt, 22 Objekte wurde durch visuelle Spektroskopie gefunden. Das einzige fotografische Objekt ist der Maja-Nebel NGC 1432 in den Plejaden, den die Brüder Henry in Paris im Jahr 1885 aufnahmen.

Nachfolgekataloge und Korrekturen

Index-Kataloge

Dreyer beobachtete insbesondere die Veröffentlichung von neuen Nebel und Sternhaufen mit großer Aufmerksamkeit. Nach der Veröffentlichung des NGC 1888 sammelten Dreyer und andere Astronomen Korrekturen und ergänzende Daten zu den NGC-Objekten. Durch den vermehrten Einsatz der Fotografie wurden viele neue nicht-stellare Objekte gefunden. Um den Überblick zu behalten, veröffentlichte Dreyer zwei Indexkataloge (Index Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars, IC I und IC II): Der Index Katalog I von 1895 enthält 1529 Objekte, die zwischen Jahren 1888 bis 1894 gefunden wurden. Die meisten der neuen Objekte des IC 1 wurden von Stéphane Javelle (794), Lewis Swift (315) und Guillaume Bigourdan (134) entdeckt. Der Index Katalog II von 1908 enthält 3857 Einträge zu Objekten, die zwischen 1895 und 1907 gefunden wurden. Entdeckt wurden diese u. a. von Max Wolf (1117), Delisle Stewart (672), Stéphane Javelle (637), Royal Frost (454), Lewis Swift (270) und Guillaume Bigourdan (188). Dreyer nutzte in jedem der Index-Kataloge die Gelegenheit, bekannte Korrekturen und zusätzliche Daten zu den NGC Einträgen aufzunehmen.[2] Eine Liste von Korrekturen der IC wurde von Dreyer 1912 veröffentlicht.[7]

Revised New General Catalogue

Aber auch nach den Korrekturen durch den IC-Katalog enthielt der New General Catalogue noch Fehler, die einfach reproduziert werden konnten. Es bestand daher der Wunsch nach einem überarbeiteten NGC, der historische und moderne Daten miteinander verbindet. Die ersten Versuche wurden 1977 und 1988 unternommen, aber keiner von beiden war zufriedenstellend.

Der erste Katalog mit dem Ziel, den ursprünglichen NGC zu aktualisieren, war der Revised New General Catalogue (RNGC) von Jack Sulentic und William Tifft, der im Jahr 1977 vorgestellt wurde. Der Versuch, Dreyers Arbeit mit modernen Daten zu verbessern, scheiterte jedoch. Die Autoren ignorierten nicht nur die bereits veröffentlichten Korrekturen, sondern führten auch eine beträchtliche Anzahl neuer Fehler ein. So wird beispielsweise die bekannte kompakte Galaxiengruppe Copeland Septet in der Konstellation Löwe im RNGC als nicht existent bezeichnet. Außerdem wurde an Orten, an denen kein Objekt gefunden werden konnte (hauptsächlich aufgrund falscher Positionen) dem nächstgelegenen ‚anonymen‘ Kandidaten oft eine RNGC-Nummer zugewiesen – ohne die Originaldaten oder die veröffentlichten Korrekturen zu konsultieren.[2]

NGC 2000

Der NGC 2000.0 (auch bekannt als der Complete New General Catalog and Index Catalog of Nebulae and Star Clusters) ist eine von Roger W. Sinnott unter Verwendung der J2000.0-Koordinaten angefertigte Zusammenstellung des NGC und IC. Sie wurde im Jahr 1988 veröffentlicht, genau 100 Jahre nach dem NGC. Der Katalog enthält mehrere Korrekturen, die von Astronomen im Laufe der Jahre gemacht wurden. In diesem Katalog wurden die Positionen des NGC jedoch ohne weitere Überprüfung umgerechnet auf die Epoche 2000.[2]

Revised New General Catalogue and Index Catalogue

Der Revised New General Catalogue and Index Catalogue (RNGC/IC) ist eine Zusammenstellung von Wolfgang Steinicke aus dem Jahr 2009. Es handelt sich um eine umfassende Behandlung des NGC- und IC-Katalogs.[8][9][10]

Galerie

- NGC 2683, eine Spiralgalaxie

- NGC 1 und NGC 2, die beiden ersten Einträge im Katalog, sind Spiralgalaxien.

- Der Helixnebel NGC 7293 ist ein planetarischer Nebel

- Der Irisnebel NGC 7023 ist ein Reflexionsnebel

- NGC 1300 ist eine Balken-Spiralgalaxie

- NGC 6124 ist ein offener Sternhaufen

- NGC 104 (47 Tucanae) ist ein Kugelsternhaufen

| Objekt | Name, weitere Bezeichnung | Entdeckt | Historische Zeichnung | Moderne Fotografie | Beschreibung im NGC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGC 5194 | Whirlpool-Galaxie, M51 | Charles Messier |  Lord Rosse |  | "!!! Great spiral neb" (!!!=a magnificent or otherwise significant object) |

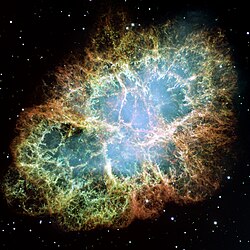

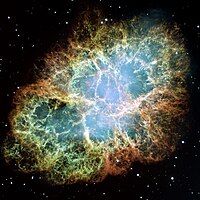

| NGC 1952 | Krebsnebel, M1 | John Bevis |  Lord Rosse |  | "vF, vS" (very faint, very small) |

| NGC 1976 | Orionnebel, M42 | N.-C. F. de Peiresc |  John Herschel |  | "!!!!Theta'Orionis and the great neb" |

| NGC 6618 | Omeganebel, M17 | J.-P. de Chéseaux |  John Herschel |  | "!!!,B, eL, eiF, 2 hooked" (bright, extremely large, extremly irregular faint) |

| NGC 1365 | James Dunlop |  John Herschel |  | "!!vB, vL, mE, rN" (very bright, very large, much extended, resolvable nucleus) | |

| NGC 5128 | Centaurus A | James Dunlop |  John Herschel |  | "!!, vB, vL, vmE 122°5 bifid" (very bright, very large, very much extended, zweigeteilt) |

Literatur

- Wolfgang Steinicke: Observing and cataloguing nebulae and star clusters : from Herschel to Dreyer’s new general catalogue. Cambridge University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-511-78953-3.

Siehe auch

- Durchmusterung

- Sternkatalog

- Sharpless-Katalog

- Liste astronomischer Kataloge

- Liste der NGC-Objekte

- Liste nicht bestätigter Einträge im New General Catalogue

Weblinks

- A new general catalogue of nebulae and clusters of stars, being the catalogue of the late Sir John F.W. Herschel (englisch)

- Komplette NGC und Messier Datenbank mit Beobachtungsberichten (deutsch)

- Verschiedene NGC-Indizes (englisch)

- Interaktiver NGC-Katalog (englisch)

- Revised New General Catalogue and Index Catalogue von Wolfgang Steinicke

- VizieR-Katalog

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Wolfgang Steinicke: GESCHICHTE/080: Die Geschichte des New General Catalogue (Sterne und Weltraum). Abgerufen am 17. Juni 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Steinicke, Wolfgang.: Observing and cataloguing nebulae and star clusters : from Herschel to Dreyer’s new general catalogue. Cambridge University Press, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-511-78953-3.

- ↑ XIX. Observations of nebulæ and clusters of stars, made at Slough, with a twenty-feet reflector, between the years 1825 and 1833. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Band 123, 31. Dezember 1833, ISSN 0261-0523, S. 359–505, doi:10.1098/rstl.1833.0021 (royalsocietypublishing.org [abgerufen am 28. Juni 2020]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k 1965ASPL....9..289L Page 289. Abgerufen am 24. Juni 2020.

- ↑ J. L. E. Dreyer: Notice of new Catalogue of Nebulae. In: Astronomische Nachrichten. Band 112, Nr. 3, 1885, S. 42–42, doi:10.1002/asna.18851120303 (wiley.com [abgerufen am 20. Juli 2020]).

- ↑ a b University of California Libraries: A new general catalogue of nebulae and clusters of stars, being the catalogue of the late Sir John F.W. Herschel. London, Royal Astronomical Society, 1888 (archive.org [abgerufen am 17. Juni 2020]).

- ↑ J. L. E. Dreyer: Corrections to the New General Catalogue resulting from the Revision of Sir William Herschel’s three Catalogues of Nebul. In: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Band 73, Nr. 1, 8. November 1912, ISSN 0035-8711, S. 37–40, doi:10.1093/mnras/73.1.37 (oup.com [abgerufen am 5. Juli 2020]).

- ↑ Wolfgang Steinicke: Revised New General Catalogue and Index Catalogue. 17. März 2019, abgerufen am 6. Juli 2020 (englisch).

- ↑ H.W. Duerbeck: Book Review: Nebel und Sternhaufen - Geschichte ihrer Entdeckung Beobachtung und Katalogisierung (Steinicke). In: Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. Band 12, Nr. 3, S. 255, bibcode:2009JAHH...12..255D.

- ↑ H.W. Duerbeck: Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters. From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue (Steinicke). In: Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. Band 14, Nr. 1, S. 78, bibcode:2011JAHH...14Q..78D.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

This is a mosaic image, one of the largest ever taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, of the Crab Nebula, a six-light-year-wide expanding remnant of a star's supernova explosion. Japanese and Chinese astronomers recorded this violent event in 1054 CE.

The orange filaments are the tattered remains of the star and consist mostly of hydrogen. The rapidly spinning neutron star embedded in the center of the nebula is the dynamo powering the nebula's eerie interior bluish glow. The blue light comes from electrons whirling at nearly the speed of light around magnetic field lines from the neutron star. The neutron star, like a lighthouse, ejects twin beams of radiation that appear to pulse 30 times a second due to the neutron star's rotation. A neutron star is the crushed ultra-dense core of the exploded star.

The Crab Nebula derived its name from its appearance in a drawing made by Irish astronomer Lord Rosse in 1844, using a 36-inch telescope. When viewed by Hubble, as well as by large ground-based telescopes such as the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope, the Crab Nebula takes on a more detailed appearance that yields clues into the spectacular demise of a star, 6,500 light-years away.

The newly composed image was assembled from 24 individual Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 exposures taken in October 1999, January 2000, and December 2000. The colors in the image indicate the different elements that were expelled during the explosion. Blue in the filaments in the outer part of the nebula represents neutral oxygen, green is singly-ionized sulfur, and red indicates doubly-ionized oxygen.P 20. Plate IV, Fig 1: h2552: NGC 1365

J. Herschel 1837

Autor/Urheber: NASA, ESA, S. Beckwith (STScI), and The Hubble Heritage Team STScI/AURA), Lizenz: CC BY 3.0

The Whirlpool Galaxy (Spiral Galaxy M51, NGC 5194) is a classic spiral galaxy located in the Canes Venatici constellation.

Out of this whirl: The Whirlpool Galaxy (M51) and companion galaxy

The graceful, winding arms of the majestic spiral galaxy M51 (NGC 5194) appear like a grand spiral staircase sweeping through space. They are actually long lanes of stars and gas laced with dust.

This sharpest-ever image, taken in January 2005 with the Advanced Camera for Surveys aboard the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, illustrates a spiral galaxy's grand design, from its curving spiral arms, where young stars reside, to its yellowish central core, a home of older stars. The galaxy is nicknamed the Whirlpool because of its swirling structure.

The Whirlpool's most striking feature is its two curving arms, a hallmark of so-called grand-design spiral galaxies. Many spiral galaxies possess numerous, loosely shaped arms that make their spiral structure less pronounced. These arms serve an important purpose in spiral galaxies. They are star-formation factories, compressing hydrogen gas and creating clusters of new stars. In the Whirlpool, the assembly line begins with the dark clouds of gas on the inner edge, then moves to bright pink star-forming regions, and ends with the brilliant blue star clusters along the outer edge.

Some astronomers believe that the Whirlpool's arms are so prominent because of the effects of a close encounter with NGC 5195, the small, yellowish galaxy at the outermost tip of one of the Whirlpool's arms. At first glance, the compact galaxy appears to be tugging on the arm. Hubble's clear view, however, shows that NGC 5195 is passing behind the Whirlpool. The small galaxy has been gliding past the Whirlpool for hundreds of millions of years.

As NGC 5195 drifts by, its gravitational muscle pumps up waves within the Whirlpool's pancake-shaped disk. The waves are like ripples in a pond generated when a rock is thrown in the water. When the waves pass through orbiting gas clouds within the disk, they squeeze the gaseous material along each arm's inner edge. The dark dusty material looks like gathering storm clouds. These dense clouds collapse, creating a wake of star birth, as seen in the bright pink star-forming regions. The largest stars eventually sweep away the dusty cocoons with a torrent of radiation, hurricane-like stellar winds, and shock waves from supernova blasts. Bright blue star clusters emerge from the mayhem, illuminating the Whirlpool's arms like city streetlights.

The Whirlpool is one of astronomy's galactic darlings. Located 31 million light-years away in the constellation Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs), the Whirlpool's beautiful face-on view and closeness to Earth allow astronomers to study a classic spiral galaxy's structure and star-forming processes.

Credit:

NASA, ESA, S. Beckwith (STScI), and The Hubble Heritage Team STScI/AURA)

About the Image

NASA caption Id: heic0506a Type: Observation Release date: 25 April 2005, 06:00 Related releases: heic0506 Size: 11477 x 7965 px

About the Object

Name: Messier 51, Whirlpool Galaxy Type: • Local Universe : Galaxy : Type : Spiral • Galaxies Images/Videos Distance: 25 million light years

Colours & filters

Band Wavelength Telescope Optical B 435 nm Hubble Space Telescope ACS Optical V 555 nm Hubble Space Telescope ACS Optical H-alpha + Nii 658 nm Hubble Space Telescope ACS Infrared I 814 nm Hubble Space Telescope ACS.

John Herschels Teleskop bei Feldhausen am Kap der Guten Hoffnung 1834 in Suedafrika. Scan vom Original, um 1847, Gemeinfrei durch Alter.

Erste Katalog-Seite aus dem "New General Catalogue" von John Ludvig Emil Dreyer: NGC 1 bis NGC 33.

"No.": Fortlaufende Nummer im NGC. "G.C.": Nummer in "General Catalogue" von John Herrschel (1-5079) oder der ersten Erweiterung von Dreyer (5080-6251) "J.H.": Nummer der Slough Beobacthungen in Phil. Trans und seiner Beobachtungen vom Kap. "W.H.": Klassifikation und Nummer von William Herrschel aus den Beobachtungen von 1786, 1789, 1802. "Other Obervers.": Weitere Beobachter des Objekts. Häufig auftretende Namen wurden von Dreyer abgekürzt, z.B: "d'A für d'Arrest, Auw. für Auwers." "Right Ascension, 1860": Rektaszension für die Epoche 1860 "Annual Precession, 1880": Jährliche Präzession der Rektaszension im Jahre 1880 "North Polar Distance 1860": Entfernung vom Nordpol in Winkelgrad für die Epoche 1860 "Annual Precession, 1880": Jährliche Präzession der Deklination im Jahre 1880

"Summary Description": In dieser Spalte werden in Kurzform die wesentliche Eigenschaften des Objekts angeben (Helligkeit, Größe, Form, besondere Merkmale)Results of astronomical observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8, at the Cape of Good Hope; being the completion of a telescopic survey of the whole surface of the visible heavens, commenced in 1825

https://archive.org/details/philtrans07546441

Cropped,inverterted, gauss filtered, gamma corrected

Observations on Some of the Nebulae by Earl of Rosse, .

Publication date 1844-01-01 Usage Public Domain Mark 1.0 Topics Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Publisher Royal Society of London Collection philosophicaltransactions; additional_collections Language English Observations on Some of the Nebulae. Earl of Rosse, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (1776-1886). 1844-01-01. 134:321–324 Identifier philtrans07546441 Identifier-ark ark:/13960/t40s0q23v Identifier-doi 10.1098/rstl.1844.0012 Journal-title Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (1776-1886) Journal-volume 134 Ocr ABBYY FineReader 8.0 Originalurl https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1844.0012 Page-ending 324

Page-starting 321The NASA Hubble Space Telescope has spotted the "UFO Galaxy." NGC 2683 is a spiral galaxy seen almost edge-on, giving it the shape of a classic science fiction spaceship. This is why the astronomers at the Astronaut Memorial Planetarium and Observatory, Cocoa, Fla., gave it this attention-grabbing nickname.

While a bird's eye view lets us see the detailed structure of a galaxy (such as this Hubble image of a barred spiral), a side-on view has its own perks. In particular, it gives astronomers a great opportunity to see the delicate dusty lanes of the spiral arms silhouetted against the golden haze of the galaxy’s core. In addition, brilliant clusters of young blue stars shine scattered throughout the disc, mapping the galaxy’s star-forming regions.

Perhaps surprisingly, side-on views of galaxies like this one do not prevent astronomers from deducing their structures. Studies of the properties of the light coming from NGC 2683 suggest that this is a barred spiral galaxy, even though the angle we see it at does not let us see this directly.

This image is produced from two adjacent fields observed in visible and infrared light by Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys. A narrow strip which appears slightly blurred and crosses most the image horizontally is a result of a gap between Hubble’s detectors. This strip has been patched using images from observations of the galaxy made by ground-based telescopes, which show significantly less detail. The field of view is approximately 6.5 by 3.3 arcminutes.Autor/Urheber: European Southern Observatory, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

Three-colour composite image of the Omega Nebula (Messier 17, or NGC 6618), based on images obtained with the EMMI instrument on the ESO 3.58-metre New Technology Telescope at the La Silla Observatory. North is down and East is to the right in the image. It spans an angle equal to about one third the diameter of the Full Moon, corresponding to about 15 light-years at the distance of the Omega Nebula. The three filters used are B (blue), V ("visual", or green) and R (red).

A photograph believed to have been taken in 1883 which shows the north face of the Armagh Observatory buildings. In the foreground we see the meteorological enclosure on the North Lawn containing the Square Rain Gauge (S2) and the Beckley Automatic Raingauge (Kew). On the roof of the main building we see the Robinson Cup Anemometer by Munroe with its recording apparatus, to the right, and the Campbell-Stokes Sunshine recorder to the left. Attached to the north window of the East Tower we see the metal box that contained the thermometers and behind the East Tower we see a part of the housing of the automatic thermograph by Beckley.

Autor/Urheber: Hewholooks, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Iris Nebula LBN 487 and NGC 7023 in Cepheus

Barred spiral galaxy NGC 1300 photographed by Hubble telescope.

In the core of the larger spiral structure of NGC 1300, the nucleus shows its own extraordinary and distinct "grand-design" spiral structure that is about 3,300 light-years (1 kiloparsec) long. Only galaxies with large-scale bars appear to have these grand-design inner disks — a spiral within a spiral. Models suggest that the gas in a bar can be funneled inwards, and then spiral into the center through the grand-design disk, where it can potentially fuel a central black hole. NGC 1300 is not known to have an active nucleus, however, indicating either that there is no black hole, or that it is not accreting matter.

Autor/Urheber: ESO, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

This image of Centaurus A, also known as NGC 5128, is an example of how frontier science can be combined with aesthetic aspects. This galaxy is a most interesting object and is being investigated by means of observations in all spectral regions, from radio via infrared and optical wavelengths to X- and gamma-rays. It is one of the most extensively studied objects in the southern sky.

Дрейер Джон Людвиг Эмиль

Ansicht des Orionnebels erstellt durch das Hubble-Weltraumteleskop. Die Aufnahme wurde während105 Erdumläufen des Teleskops erstellt und ist eine der detailliertesten Ansichten des Nebels. Die Gesamtfläche des Fotos entspricht etwa der des Vollmondes.

Autor/Urheber: ESO/M.-R. Cioni/VISTA Magellanic Cloud survey. Acknowledgment: Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

This new infrared image from ESO’s VISTA telescope shows the globular cluster 47 Tucanae in striking detail. This cluster contains millions of stars, and there are many nestled at its core that are exotic and display unusual properties. Studying objects within clusters like 47 Tucanae may help us to understand how these oddballs form and interact. This image is very sharp and deep due to the size, sensitivity, and location of VISTA, which is sited at ESO's Paranal Observatory in Chile.

Globular clusters are vast, spherical clouds of old stars bound together by gravity. They are found circling the cores of galaxies, as satellites orbit the Earth. These star clumps contain very little dust and gas — it is thought that most of it has been either blown from the cluster by winds and explosions from the stars within, or stripped away by interstellar gas interacting with the cluster. Any remaining material coalesced to form stars billions of years ago.

These globular clusters spark a considerable amount of interest for astronomers — 47 Tucanae, otherwise known as NGC 104, is a huge, ancient globular cluster about 15 000 light-years away from us, and is known to contain many bizarre and interesting stars and systems.

Located in the southern constellation of Tucana (The Toucan), 47 Tucanae orbits our Milky Way. At about 120 light-years across it is so large that, despite its distance, it looks about as big as the full Moon. Hosting millions of stars, it is one of the brightest and most massive globular clusters known and is visible to the naked eye [1]. In amongst the swirling mass of stars at its heart lie many intriguing systems, including X-ray sources, variable stars, vampire stars, unexpectedly bright “normal” stars known as blue stragglers (eso1243), and tiny objects known as millisecond pulsars, small dead stars that rotate astonishingly quickly [2].

Red giants, stars that have exhausted the fuel in their cores and swollen in size, are scattered across this VISTA image and are easy to pick out, glowing a deep amber against the bright white-yellow background stars. The densely packed core is contrasted against the more sparse outer regions of the cluster, and in the background huge numbers of stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud are visible.

This image was taken using ESO’s VISTA (Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy) as part of the VMC survey of the region of the Magellanic Clouds, two of the closest known galaxies to us. 47 Tucanae, although much closer than the Clouds, by chance lies in the the foreground of the Small Magellanic Cloud (eso1008), and was snapped during the survey.

VISTA is the world’s largest telescope dedicated to mapping the sky. Located at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile, this infrared telescope, with its large mirror, wide field of view and sensitive detectors, is revealing a new view of the southern sky. Using a combination of sharp infrared images — such as the VISTA image above — and visible-light observations allows astronomers to probe the contents and history of objects like 47 Tucanae in great detail. Notes

[1] There are over 150 globular clusters orbiting our galaxy. 47 Tucanae is the second most massive after Omega Centauri.

[2] Millisecond pulsars are incredibly quickly rotating versions of regular pulsars, highly magnetised, rotating stellar remnants that emit bursts of radiation as they spin. There are 23 known millisecond pulsars in 47 Tucanae — more than in all other globular clusters bar one, Terzan 5.Autor/Urheber: ESO, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

This is a true-colour image of the major part of NGC 1365, combined from three exposures with the FORS1 multi-mode instrument at VLT UT1, in the B (blue), V (green) and R (red) optical bands. The exposure times were 360, 180 and 140 seconds, respectively. The image quality is about 0.8 arcsec. The field measures about 7 x 7 arcmin 2. North is up and East is left.

ID: phot-08a-99

Press Release: 05/99

Long Caption: http://www.eso.org/public/outreach/press-rel/pr-1999/phot-08-99.html

Object: NGC 1365

Telescope: UT1/Antu

Instrument: FORS1

Size: 2039x2037

Credit: ESOZeichnung der Galaxie "Centaurus A" (NGC 5128) von John Herschel

Autor/Urheber: Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

Angle of view: 4' × 4' (0.3" per pixel), north is up.

Details on the image processing pipeline: https://www.sdss.org/dr14/imaging/jpg-images-on-skyserver/Autor/Urheber: Roberto Mura, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

NGC 6124 (taken from Stellarium)

The Helix Nebula: a Gaseous Envelope Expelled By a Dying Star

- About the Object

- Object Name: Helix Nebula, NGC 7293 or "The Eye of God"

- Object Description: Planetary Nebula

- Position (J2000): R.A. 22h 29m 48.20s

- Dec. -20° 49' 26.0"

- Constellation: Aquarius

- Distance: About 690 light-years (213 parsecs)

- Dimensions: The image is roughly 28.7 arcminutes (5.6 light-years or 1.7 parsecs) across.

- About the Data

- Instruments: ACS/WFC on Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and Mosaic II Camera on CTIO 4m telescope

- Exposure Time: 4.5 hours (HST) and 10 minutes (CTIO)

- Filters: F502N ([O III]) and F658N (Ha) (for the HST); c6009 (H alpha)and kc6014 ([O III]) for the CTIO

- Image properties

- Centered on white dwarfed and cropped

- Downsampled to 3200x3200

- Saved as jpg, quality 8/10, 5 scans

- Stitching errors manually fixed