Myzozoa

| Myzozoa | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Membranstruktur der Myzozoa | ||||||||||||

| Systematik | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Wissenschaftlicher Name ohne Rang | ||||||||||||

| Miozoa | ||||||||||||

| Cavalier-Smith 1987 | ||||||||||||

| Wissenschaftlicher Name ohne Rang | ||||||||||||

| Myzozoa | ||||||||||||

| Cavalier-Smith & Chao 2004 |

- Nicht zu verwechseln mit Myxozoa.

Myzozoa[1] ist eine Gruppe bestimmter Untergruppen (Kladen, teilweise als Phyla angesehen) innerhalb der Alveolata,[2][3] die sich entweder per Myzozytose ernähren oder von Vorfahren abstammen, die dazu in der Lage waren.[1] Auch die Myzozoa werden manchmal als Phylum bezeichnet. Als Hauptuntergruppen schließen die Myzozoa die Dinozoa (mit den Dinoflagellaten) und die Apicomplexa ein, sowie weitere kleinere Gruppen.[4] Daher werden insgesamt eine recht große Zahl von Ordnungen der Protisten zu den Myzozoa gezählt.[1][5]

Der Begriff Myzozoa löst im Gebrauch den Begriff Miozoa der gleichen Autorenschaft ab, der veränderte, d. h. umfangreichere Bedeutung hat.[1]

Innere Systematik

Die Systematik der Miozoa respektive Myzozoa ist ungefähr wie folgt:[6]

Miozoa Cavalier-Smith, 1987

- Protalveolata Cavalier-Smith, 1991(#) – nicht monophyletisch (s. u.)

- Acavomonidia Tikhonenkov et al. 2014 mit Acavomonas peruviana Tikhonenkov et al. 2014 [Colponema sp. Peru]

- Colponemidia Cavalier-Smith, 1993 mit Colponema loxodes Stein, 1878

- Myzozoa Cavalier-Smith & Chao, 2004[1] – mit circa vier Hauptuntergruppen („Phyla“):

- Dinozoa Cavalier-Smith, 1981

- Dinoflagellata Bütschli, 1885 (Dinoflagellaten)(#)

- Perkinsozoa Norén et al., 1999(#)[A. 1]

- ?…[A. 2]

- Apicomplexa Levine, 1970 (sensu lato)[1][6] – Bezeichnung in diesem Sinn nicht mehr gebräuchlich

- Apicomplexa Levine 1980, emend. Adl et al. 2005(#) (sensu stricto) [Sporozoa Leuckart, 1879[1][6]] (inkl. Gregarinen, Kokzidien, Coralli- und Ichthyocoliden)

- Squirmida Cavalier-Smith, 2014 (neu, ausgegliedert aus der Apicomplexa-Gruppe der Gregarinen)

- Chrompodellida (Chromerida(#) und Colpodellida) [früher Apicomonada Cavalier-Smith, 1993][A. 3]

(#) – herkömmliche Untergruppen der Miozoa bzw. Myzozoa nach Thomas Cavalier-Smith (1987, 2004), das sind:

- Apicomplexa – parasitische Protisten, die außer in den Gameten keine Fortbewegungsstrukturen mit Axonemen (Geißeln), keine Photosynthese durchführen (mit Ausnahme der Corallicolida auch kein Chlorophyll besitzen)

- Chromerida – eine Gruppe photosynthetisch aktiber mariner Protisten, ergänzt um ihre Verwandten ohne Photosynthese (Colpodellida)

- Dinoflagellaten – meist marine Flagellaten, von denen viele Chloroplasten haben

- Perkinsozoa

- Protalveolata (Mitglied der Miozoa, nicht Myzozoa)

Der Begriff respekive die Gruppe Myzozoa wurde zwar in einer Auflistung der Protistengruppen von Adl et al. (2012) nicht berücksichtigt,[12] wird aber in neuern Arbeiten wieder bzw. immer noch verwendet.[10]

Die strenge Taxonomie berücksichtigt nur die gemeinsamen Merkmale aller Organismen einer Gruppe. Einige Organismen innerhalb der einzelnen Gruppen der Myzozoa haben jedoch die charakteristische Fähigkeit zur Myzozytose verloren. Da die Taxonomie die molekulare Phylogenie nicht berücksichtigt, werden in einer solchen Klassifikation alle Alveolata-Taxa mit Ausnahme der Apikomplexa, Wimpertierchen und Dinoflagellaten summarisch unter dem (nicht-taxonomischen) Sammelbegriff „Protalveolata“ geführt.[12]

Die Schwierigkeit, sehr frühe Dinozoa entweder innerhalb oder außerhalb der Gruppe „Dinoflagellaten“ einzuordnen (siehe Dinozoa §Systematik), begünstigt weiterhin solche Klassifizierungen wie Protalveolata,[12] ähnlich wie die mögliche Polyphylie zwischen den beiden Colpodelliden-Gattungen Voromonas und Colpodella.[1]

Evolution/Phylogenie

Beide Organismengruppen scheinen ein lineares mitochondriales Genom zu besitzen; die meisten anderen Eukaryonten, deren mitochondriales Genom untersucht wurde, haben zirkuläre Genome – nach der Endosymbiontentheorie stammen die Mitochondrien von α-Proteobakterien ab (siehe Mitochondrium §Ursprung).

Der taxonomische Begriff Myzozoa schließt explizit die Wimpertierchen (Ciliophora) aus, die unter den Alveolata stattdessen einen höheren taxonomischen Rang einnehmen.[1] Die Alveoata umfassen damit zwei große Gruppen: Die Myzozoa und die Ciliophora,[13] sowie einige kleineren Gruppen (s. o. Sammelbegriff „Protalveolata“).

Alle Myzozoa scheinen sich von einem Vorfahren abzustammen, der vermutlich ein biflagellater, myzozytotischer Räuber war[10] und seine (komplexen) Plastiden per Endosymbiose mit Rotalgen erworben hatte.[14][15][16] Der Parasitismus entwickelte sich bei den Myzozoa danach mehrfach unabhängig voneinander; dabei gingen die Geißeln beim jüngsten Vorfahren der Apicomplexa (=Sporozoa) verloren.[10]

Die Topologie (Reihenfolge der Verzweigungen) innerhalb der Miozoa (d. h. Myzozoa und „Protalveolata“) ist nur teilweise geklärt. Die Gruppen Chrompodellida (Colpodellida-Chromerida) und Apicomplexa (früher Sporozoa genannt) scheinen Schwestergruppen zu sein.[17][10]

Eine weitere kleine Gruppe, die Squirmida, besteht derzeit (Stand 2024) aus drei Gattungen, die früher der Apicomplexa-Gruppe der Gregarinen zugeordnet wurden, u. a, weil ihr „Vorderer Apparat“ (englisch anterior apparatus) dem Mucron[A. 4] der Gregarinen äußerlich ähnelt.[10]

Drei weitere Gruppen – die Perkinssozoa, Syndiniales und die Gattung Oxyrrhis – sind mit den Dinoflagellaten entfernt verwandt (Perkinssozoa) oder gehören möglicherweise zu ihnen, in basaler Position vom Rest abzweigend (Syndiniales, Oxyrrhis).[9][20][10] Genetische Analysen auf der Ebene der Haupt- und Nebenuntereinheiten der rDNA des Zellkerns (Kerngenom) durch Robert Moore et al. (2008)[17] und Denis Tikhonenkov (2014),[21] sowie Analysen durch Thomas Cavalier-Smith (2017)[22] führten – nach Ausgliederung der Squirmida[10] zu den folgenden phylogenetischen Beziehungen:

| Alveolata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(#) – unter Sammelbegriff „Protalveolata“

Bildergalerie

- Oxyrrhis marina, Dinoflagelaten, Illustration um 1900

- Ceratium furca.jpg, Gonyaulacales (Dinoflagellaten)

Anmerkungen

- ↑ a b Perkinsus marinus und die Apicomplexa haben beide Histone, während die Dinoflagellaten ihre Histone verloren zu haben scheinen.[7]

- ↑ Früher galt die Gattung Oxyrrhis als (knapp ) außerhalb der Dinoflagellaten stehend, heute als in basal Position innerhalb derselben; dafür werden heute eher die Syniniales ausgegliedert[8][9][10]

- ↑ a b Die Chromerida sind ursprünglich myzozytotisch, was durch den Nachweis der Myzozytose bei ihrem Mitglied Vitrella brassicaformis belegt ist.[11]

- ↑ a b Das Mucron ist ein „Anheftungsorganell“ (englisch attachment organelle) der Archigregarinen und phänotypisch ähnlicher epizellulärer (an der Außenseite der Wirtszellen) parasitischer Alveolata aus der Apicomplexa-Verwandtschaft (d. h. den Myzozoa). Man nimmt an, dass es sich vom apikalen Komplex ableitet.[18][19][12] Offensichtlich bezeichnet der Ausdruck das selbe, was bei anderen Autoren „Vorderer Apparat“ (englisch anterior apparatus) genannt wird – vielleicht, weil der Ausdruck „Mucron“ den eigentlichen Gregarinen vorbehalten bleiben soll.

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Thomas Cavalier-Smith, Ema E. Chao: Protalveolate phylogeny and systematics and the origins of Sporozoa and dinoflagellates (phylum Myzozoa nom. nov.). In: European Journal of Protistology. 40. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, September 2004, S. 185–212, doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2004.01.002 (englisch).

- ↑ Brian S. Leander, Mona Hoppenrath: Ultrastructure of a novel tube-forming, intracellular parasite of dinoflagellates: Parvilucifera prorocentri sp. nov. (Alveolata, Myzozoa). In: European Journal of Protistology, Band 44, Nr. 1, Februar 2008, S. 55–70; doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2007.08.004, PMID 17936600 (englisch).

- ↑ Brian S. Leander: Alveolates. Auf: Tree of Life Web Project (tolweb.org) Version 16, Stand:September 2008.

- ↑ Thomas Cavalier-Smith: Only six kingdoms of life. In: Proc. Biol. Sci. 271. Jahrgang, Nr. 1545, Juni 2004, S. 1251–62, doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2705, PMID 15306349, PMC 1691724 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Rinske M. Valster, Bart A. Wullings, Geo Bakker, Hauke Smidt, Dick van der Kooij: Free-living protozoa in two unchlorinated drinking water supplies identified by phylogenic analysis of 18S rRNA gene sequences. In: Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 75. Jahrgang, Nr. 14, Mai 2009, S. 4736–4746, doi:10.1128/AEM.02629-08, PMID 19465529, PMC 2708415 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ a b c Taxon: Subphylum Myzozoa Cavalier-Smith & Chao, 2004 (protist). The Taxonomicon. Universal Taxonomic Services, Zwaag, Niederlande (taxonomy.nl). Stand: 1. Februar 2024.

- ↑ Sebastian G. Gornik, Kristina L. Ford, Terrence D. Mulhern, Antony Bacic, Geoffrey I. McFadden, Ross F. Waller: Loss of nucleosomal DNA condensation coincides with appearance of a novel nuclear protein in dinoflagellates. In: Current Biology. 22. Jahrgang, Nr. 24, Dezember 2012, S. 2303–2312, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.036, PMID 23159597 (englisch).

- ↑ Sina M. Adl et al.: The New Higher Level Classification of Eukaryotes with Emphasis on the Taxonomy of Protists. The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, Band 52, 2005, S. 399–451; doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x (englisch).

- ↑ a b Juan F. Saldarriaga, Michelle L. McEwan, Naomi M. Fast, F. J. R. Taylor, Patrick J. Keelin1: Multiple protein phylogenies show that Oxyrrhis marina and Perkinsus marinus are early branches of the dinoflagellate lineage. In: International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, Band 53, Nr. 1, 1. Januar 2003, S. 355–365; doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02328-0, PMID 12656195, ResearchGate:10839460 (englisch).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Danja Currie-Olsen, Brian S. Leander: Novel cytoskeletal traits in the intestinal parasites (Squirmida, Platyproteum vivax) of Pacific peanut worms (Sipuncula, Phascolosoma agassizii). In: Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, Band 71, Nr. 3, 25. Februar 2024, S. e13023; doi:10.1111/jeu.13023 (englisch) Siehe insbes. Fig. 1.

- ↑ Robert Bruce Moore: Molecular ecology and phylogeny of protistan algal symbionts from corals. Postgraduate Thesis, School of Molecular and Microbial Biosciences, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, 1. Januar 2006, WorldCat:271214031. Memento im Webarchiv vom 26. Juli 2024 (englisch).

- ↑ a b c d Sina M. Adl, Alastair G. B. Simpson, Christopher E. Lane, Julius Lukeš, David Bass, Samuel S. Bowser, Matthew W. Brown, Fabien Burki, Micah "Cavalier2004-09"§Cavalier2004"Dunthorn, Vladimir Hampl, Aaron Heiss, Mona Hoppenrath, Enrique Lara, Line le Gall, Denis H. Lynn, Hilary McManus, Edward A. D. Mitchell, Sharon E. Mozley-Stanridge, Laura W. Parfrey, Jan Pawlowski, Sonja Rueckert, Laura Shadwick, Conrad L. Schoch, Alexey Smirnov, Frederick W. Spiegel: The revised classification of eukaryotes. In: Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 59. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, 28. August 2012, S. 429–493, doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x, PMID 23020233, PMC 3483872 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Wikispecies: Protalveolata

- ↑ Sethu C. Nair, Boris Striepen: What Do Human Parasites Do with a Chloroplast Anyway? In: PLoS Biology. Band 9, Nr. 8, 2011, S. e1001137, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001137, PMID 21912515, PMC 3166169 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Patrick J. Keeling: The endosymbiotic origin, diversification and fate of plastids. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Band 365, Nr. 1541, 2010, S. 729–48, doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0103, PMID 20124341, PMC 2817223 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

- ↑ Sergio A. Muñoz-Gómez, Claudio H. Slamovits: Plastid Genome Evolution (= Advances in Botanical Research. Band 85). 2018, ISBN 978-0-12-813457-3, Plastid Genomes in the Myzozoa, S. 55–94, doi:10.1016/bs.abr.2017.11.015 (englisch).

- ↑ a b Robert B. Moore, Miroslav Oborník, Jan Janouškovec, Tomáš Chrudimský, Marie Vancová, David H. Green, Simon W. Wright, Noel W. Davies, Christopher J. S. Bolch, Kirsten Heimann, Jan Šlapeta, Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, John M. Logsdon, Dee A. Carter: A photosynthetic alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites. In: Nature. 451. Jahrgang, Nr. 7181, Februar 2008, S. 959–963, doi:10.1038/nature06635, PMID 18288187, bibcode:2008Natur.451..959M (englisch). Siehe insbes. Fig. 2: Nuclear and plastid phylogenies of Chromera velia (Memento im Webarchiv vom 17. Januar 2013).

- ↑ F. O. Perkins, J. R. Barta, R. E. Clopton, M. A. Peirce, S. J. Upton: An Illustrated guide to the Protozoa: organisms traditionally referred to as protozoa, or newly discovered groups. Hrsg.: J. J. Lee, G. F. Leedale, P. Bradbury. 2. Auflage. Band 1. Society of Protozoologists, 2000, ISBN 1-891276-22-0, Phylum Apicomplexa, S. 190–369 (englisch).

- ↑ Timur G. Simdyanov, Laure Guillou, Andrei Y. Diakin, Kirill V. Mikhailov, Joseph Schrével, Vladimir V. Aleoshin: A new view on the morphology and phylogeny of eugregarines suggested by the evidence from the gregarine Ancora sagittata (Leuckart, 1860) Labbé, 1899 (Apicomplexa: Eugregarinida). In: PeerJ, Band 5, 30. Mai 2017, S. e3354; doi:10.7717/peerj.3354 (englisch).

- ↑ Brian S. Leander, Olga N. Kuvardina, Vladimir V. Aleshin, Alexander P. Mylnikov, Patrick J. Keeling: Molecular phylogeny and surface morphology of Colpodella edax (Alveolata): insights into the phagotrophic ancestry of apicomplexans. In: Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, Band 50, Nr. 5, September 2003, S. 334–340; doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00145.x, PMID 14563171, Epub 11. Juli 2005 (englisch).

- ↑ Denis V. Tikhonenkov, Jan Janouškovec, Alexander P. Mylnikov, Kirill V. Mikhailov, Timur G. Simdyanov, Vladimir V. Aleoshin, Patrick J. Keeling: Description of Colponema vietnamica sp.n. and Acavomonas peruviana n. gen. n. sp., Two New Alveolate Phyla (Colponemidia nom. nov. and Acavomonidia nom. nov.) and Their Contributions to Reconstructing the Ancestral State of Alveolates and Eukaryotes. In: PLOS ONE! Band 9, Nr. 14, 16. April 2014; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095467 (englisch).

- ↑ Thomas Cavalier-Smith: Kingdom Chromista and its eight phyla: a new synthesis emphasising periplastid protein targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid evolution, and ancient divergences. In: Protoplasma. 255. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 5. September 2017, S. 297–357, doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1147-3, PMID 28875267, PMC 5756292 (freier Volltext) – (englisch).

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Autor/Urheber: Danja Currie-Olsen & Brian S. Leander, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

Differential interference contrast (DIC) light micrographs of living trophozoites of Platyproteum vivax showing general morphology.

- (A) An elongated trophozoite viewed from the lateral edge showing the flatness of the cell, the anterior apparatus (bracket) and the flattened nucleus (N).

- (B) A semi-contracted trophozoite showing the anterior apparatus oriented to the right (bracket), the dorsal surface of the cell, and the central position of the oval nucleus (N).

Autor/Urheber: Danja Currie-Olsen & Brian S. Leander, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

Synthetic tree reflecting the current phylogenetic framework of myzozoans (ciliates included as the outgroup). The tree shows that the Squirmida (Platyproteum spp., Filipodium, and Digyalum) branch separately from gregarines and form the sister lineage to a clade consisting of apicomplexans and chrompodellids. The myzozoan ancestor is inferred to have been a biflagellated, myzocytotic-feeding predator. Parasitism evolved independently multiple times within the Myzozoa, and flagella were lost in the most recent ancestor of apicomplexans in association with the origin of parasitism. The phylogenetic positions of the specific lineage investigated in this study, namely Platyproteum vivax, and the lineage of gregarine apicomplexans that most closely resembles Platyproteum, namely Selenidium, are written in bold.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny of Squirmida according to Danja Currie-Olsen & Brian S. Leander (2024). |

Enlarge image for index to numbers.

- Ceratium tripos (Nitsch) = Neoceratium tripos (O.F.Müller) F.Gomez, D.Moreira & P.Lopez-Garcia

- Ornithocercus magnificus (Stein) = Ornithocercus magnificus Stein

- Ceratocorys horrida (Stein) = Ceratocorys horrida Stein

- Goniodoma acuminatum (Stein) = Triadinium polyedricum (Pouchet) Dodge

- Dinophysis homunculus (Stein) = Dinophysis caudata Saville-Kent

- Dinophysis sphaerica (Stein) = Dinophysis sphaerica Stein

- Ceratium cornutum (Claparède) = Ceratium cornutum (Ehrenberg) Claparède & J. Lachmann

- Ceratium macroceros (Schrank) = Ceratium hirundinella (O.F.Müller) Dujardin

- Pyrgidium pyriforme (Haeckel) = Pyrgidium pyriforme E.H.P.A.Haeckel

- Peridinium divergens (Ehrenberg) = Protoperidinium divergens (Ehrenberg) Balech

- Histioneis remora (Stein) = Histioneis remora Stein

Autor/Urheber: Minami Himemiya, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Hydrofront of Dnieper-Bug Liman

Oxyrrhis marina

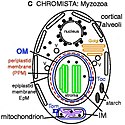

Autor/Urheber: Thomas Cavalier-Smith (caption slightly moved, digitylly enhanced), Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Membrane structre of an algal chromista cell (myzozoa). These originated by secondary intracellular enslavement of a red algal plant cell. Both target nuclear-coded proteins to plastids by transit peptides (TPs) recognised by outer membrane (OM, blue) Toc receptors and to mitochondria (enslaved α-proteobacteria) by topogenic sequences recognised by OM Tom receptors. For clarity, peroxisomes and lysosomes omitted.

Myzozoa lack periplastid ribosomes, phycobilins, and nucleomorph DNA; thylakoids are stacked in threes; PPM (present in Apicomplexa—red dashed line; lost in Dinozoa) and plastids are not within the rough ER. The original phagosome membrane (now epiplastid membrane, EpM) remains smooth and receives vesicles (V) containing nucleus-encoded plastid proteins from the Golgi. Dinozoa lack PR, but Apicomplexa have a likely homologue (not shown).