Marmorierung

Marmorierung bezeichnet eine dem Marmor ähnliche Oberflächenstruktur[1] oder auch deren Herstellung. Als bekannte Beispiele lassen sich Glasgegenstände wie Oralit, duroplastische Kunststoffe wie Kunsthorn oder Bakelit und schließlich Oberflächenstrukturen an Wänden wie Stuckmarmor anführen. Eine Marmorierung im weiteren Sinne weist das besonders gestaltete Marmorpapier auf.

Eine kühle, feuchte, blass-zyanotische oder als Folge der Durchblutungsdrosselung marmorierte Haut kann ein Hinweis auf ein Schockgeschehen sein.[2]

- Marmorierter Orgelprospekt

18. Jh. - Marmorierte Säulen (Stuckmarmor),

19./20. Jh. - Englisches Marmorpapier, 19. Jh.

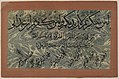

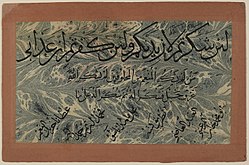

- Marmoriertes Kalligraphiepapier, Arabien, 18. Jh.

- Nest mit braun marmorierten Vogeleiern

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ marmorieren. In: Duden.

- ↑ Wolfgang Gerok u. a. (Hrsg.): Die Innere Medizin. Referenzwerk für den Facharzt. 11. Auflage. Schattauer. Stuttgart / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-7945-2222-4, S. 1464.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Handgefertigtes marmoriertes Vorsatzpapier (identisch mit Einbandüberzug) eines Buches, das um 1830 in England handgebunden wurde.

Autor/Urheber: Birgit Schoppe, Berlin, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Unknown eggs from Norway

Dimensions of Written Surface: 20 (w) x 11.5 (h) cm

Script: thuluth, Persian naskh, and tawqi'

This fragmentary calligraphic panel includes a verse from the Qur'an (14:7) and praises to God executed in thuluth, Persian naskh, and tawqi' scripts (Selim 1979, 171). The Qur'anic verse is written in thuluth and taken from Surat Ibrahim (Abraham). It states "(And remember, your Lord caused to be declared): If you are grateful, I will add more favors to you, but if you show ingratitude, truly My punishment is terrible." The Qur'anic verse on the top line is followed by various praises of God and His favors to men written in the Persian naskh and tawqi' scripts.

The specimen is undated but signed in the lower left corner by Abu Muhammad Khan al-Ma'rashi. Not much is known about this calligrapher, except that he also executed a number of Qur'ans and calligraphic sheets in naskh and fine riq'ah scripts. One calligraphic exercise dated Safar 1165/Dec. 1751 and signed more fully "Abu Muhammad Khan b. Sayyad Ma'rashi al-Husayni al-Ma'rashi" survives in the collections of Istanbul University Library (Bayani 1358/1939, vol. 4 entry 37). Judging by the author's Persian name and the date of the piece in Istanbul, it seems most likely that he was active in Iran during the 18th century.

Thuluth and naskh scripts are quite closely related (as one can see from the top and middle texts) while the tawqi' script used diagonally in the lower part of the fragment differs by the fact that many letters are joined with ligatures in a playful and kinetic manner. The tawqi' script takes its name from signatures and decrees, and was used principally for scrolls, diplomas, and royal documents (Zakariya 1979, 24). Arab authors of treatises dealing with calligraphy, such as al-Qalqashandi (d. 821/1418), state that the use of ligatures (tarwis) or hair-line joints (tash'rat) connecting letters to one another was obligatory for the tawqi' script (Gacek 1989, 146). The ligatures, for example between the alif (a) and mim (m), form a loop in this sample of tawqi'.

The blue and white marble paper is also typical of calligraphic panels produced in 18th century Iran and Turkey. Marbled paper (ebru in Turkish, or Kaghaz-i abri in Persian) appears to date as far back as the 16th century (Porter 1992, 53 and Porter 1988), although its use in calligraphic panels truly blooms during the 18th and 19th centuries. The particular marbling technique used in this panel is called "marbling of tide," which is created by combing the surface with an awl (Basar and Tiryaki 2000, 20). A salmon pink frame is pasted on top of the blue and white marble paper with the calligraphic exercises, and both papers are strengthened by being pasted to a thick cardboard.(c) Reinhold Möller, CC BY-SA 4.0

Orgel der evangelischen Filialkirche in Alladorf

Autor/Urheber: Steve46814, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Interior of the restored Allen County Courthouse in Fort Wayne, Indiana USA