Liste der größten Objekte im Sonnensystem

Dies ist eine Rangliste von großen Objekten im Sonnensystem in absteigender Ordnung. Meist korrelieren Durchmesser und Masse der Objekte sehr stark. Es gibt jedoch Ausnahmen wie Neptun, der zwar eine größere Masse, aber einen kleineren Durchmesser als Uranus hat. Der Planet Merkur ist kleiner, aber massereicher als die Monde Ganymed und Titan.

Liste

Die Zeile jedes hier gezeigten Satelliten hat dieselbe Farbe wie der Planet bzw. Zwergplanet, den dieser umkreist. Von Mars, Haumea, Makemake und Eris besitzt kein Satellit die ausreichende Größe, hier aufgelistet zu werden; Merkur und Venus besitzen nicht einmal Monde. Der Zwergplanet Ceres (ebenfalls mondlos) wird mit derselben Farbe wie die Asteroidengürtel-Objekte ohne Zwergplanetenstatus dargestellt.

Bei einigen transneptunischen Objekten (TNOs) besteht noch eine große Unsicherheit bezüglich Durchmesser, Masse und Albedo. Entsprechend können sich diese Werte bei veränderter Quellenlage erheblich verändern. Planet Neun kann nicht in der Liste geführt werden, da es sich dabei bisher nur um eine Hypothese handelt, ein Beweis für die Existenz dieses Planeten gibt es bisher nicht.

| Rang Ø | Name | Bild | Durchmesser (km) | Masse (kg) | Rang Masse | Dichte (g/cm³) | Objekttyp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sonne[1] |  | 1392000 | 1.989e30 | 1 | 1,408 | Stern |

| 2 | Jupiter[1] |  |

| 1.898e27 | 2 | 1,326 | 5. Planet |

| 3 | Saturn[1] |  |

| 5.683e26 | 3 | 0,687 | 6. Planet |

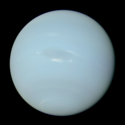

| 4 | Uranus[1] |  |

| 8.681e25 | 5 | 1,271 | 7. Planet |

| 5 | Neptun[1] |  |

| 1.024e26 | 4 | 1,638 | 8. Planet |

| 6 | Erde[1] |  |

| 5.972e24 | 6 | 5,514 | 3. Planet |

| 7 | Venus[1] |  | 12104 | 4.868e24 | 7 | 5,243 | 2. Planet |

| 8 | Mars[1] |  |

| 6.417e23 | 8 | 3,933 | 4. Planet |

| 9 | Ganymed[1] |  | 5.262 | 1.482e23 | 10 | 1,940 | Jupitermond |

| 10 | Titan[1] |  | 5.150 | 1.346e23 | 11 | 1,880 | Saturnmond |

| 11 | Merkur[1] |  | 4.879 | 3.301e23 | 9 | 5,427 | 1. Planet |

| 12 | Kallisto[1] |  | 4.821 | 1.076e23 | 12 | 1,830 | Jupitermond |

| 13 | Io[1] |  | 3.643 | 8.932e22 | 13 | 3,530 | Jupitermond |

| 14 | Mond[1] |  | 3.476 | 7.346e22 | 14 | 3,344 | Erdmond |

| 15 | Europa[1] | 3.122 | 4.800e22 | 15 | 3,010 | Jupitermond | |

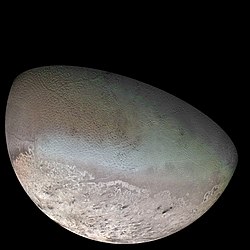

| 16 | Triton[1] |  | 2.707 | 2.14e22 | 16 | 2,050 | Neptunmond |

| 17 | (134340) Pluto[1] |  | 2.376 | 1.303e22 | 18 | 1,854 | Zwergplanet (TNO); bis 2006: 9. Planet |

| 18 | (136199) Eris[2][3][4] |  | 2.326 | 1.67e22 | 17 | 2,52 | Zwergplanet (TNO) |

| 19 | (136108) Haumea[5][6] |  | ca. 2.100 × 1.680 × 1.070 | 4.01e21 | 19 | ca. 2 | Zwergplanet (TNO) |

| 20 | Titania[1] |  | 1.578 | 3.42e21 | 20 | 1,66 | Uranusmond |

| 21 | Rhea[1] |  | 1.527 | 2.31e21 | 23 | 1,24 | Saturnmond |

| 22 | Oberon[1] |  | 1.523 | 2.88e21 | 22 | 1,56 | Uranusmond |

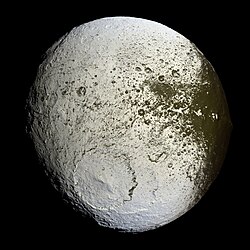

| 23 | Iapetus[1] |  | 1.469 | 1.81e21 | 24 | 1,09 | Saturnmond |

| 24 | (136472) Makemake[7][8][9] |  | 1.430 | 3.1e21 | 21 | ca. 2 | Zwergplanet (TNO) |

| 25 | (225088) Gonggong[10] |  | 1.230 | 1.75e21 | 25 | 1,75 | TNO |

| 26 | Charon[1] |  | 1.212 | 1.586e21 | 26 | 1,70 | Plutomond (TNO) |

| 27 | Umbriel[1] |  | 1.169 | 1.22e21 | 29 | 1,46 | Uranusmond |

| 28 | Ariel[1] |  | 1.158 | 1.29e21 | 28 | 1,59 | Uranusmond |

| 29 | Dione[1] |  | 1.123 | 1.10e21 | 30 | 1,48 | Saturnmond |

| 30 | (50000) Quaoar[11][12] |  | 1.120 | 1.4e21 | 27 | ca. 2 | TNO |

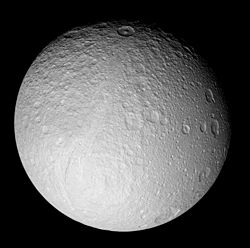

| 31 | Tethys[1] |  | 1.061 | 6.18e20 | 35 | 0,985 | Saturnmond |

| 32 | (90377) Sedna[13][A 1] |  | 995 | 1.0e21 | 31 | ca. 2 | TNO |

| 33 | (307261) 2002 MS4[14][A 2] |  | 934 | 8.5e20 | 33 | ca. 2 | TNO |

| 34 | (1) Ceres[1][15] |  | 963 × 891 | 9.393e20 | 32 | 2,162 | Zwergplanet (Asteroidengürtel) |

| 35 | (90482) Orcus[16][17] |  | 917 | 6.3e20 | 34 | 1,53 | TNO |

| 36 | (120347) Salacia[17] |  | 846 | 4.9e20 | 36 | 1,50 | TNO |

| 37 | (208996) 2003 AZ84[18][A 3] |  | ca. 940 × 766 × 490 | 2.0e20 | 42 | 0,87 | TNO |

| 38 | (55565) 2002 AW197[19][A 4] |  | 768 | 2.8e20 | 37 | ca.1.2 | TNO |

| 39 | (174567) Varda[20][21] |  | 756 | 2.66e20 | 38 | ca. 1,2 | TNO |

| 40 | (532037) 2013 FY27[22][A 5] |  | 742 | 2.6e20 | 39 | ca.1.2 | TNO |

| 41 | (90568) 2004 GV9[14][A 6] |  | 680 | 2.0e20 | 42 | ca.1.2 | TNO |

| 42 | (145452) 2005 RN43[14][A 7] |  | 679 | 2.0e20 | 42 | ca.1.2 | TNO |

| 43 | (523794) 2015 RR245[23][A 8] |  | 670 | 1.9e20 | 45 | ca.1.2 | TNO |

| 44 | (55637) 2002 UX25[16][24] |  | 665 | 1.25e20 | 50 | 0,82 | TNO |

| 45 | (20000) Varuna[25][26][A 9] |  | 654 | 1.45e20 | 46 | 0,99 | TNO |

| 46 | (229762) Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà[27][28] |  | 642 | 1.36e20 | 47 | 1,04 | TNO |

| 47 | (589683) 2010 RF43[29][A 10] | 636 | 1.3e20 | 48 | ca. 1 | TNO | |

| 48 | 2014 UZ224[30][A 11] | (c) ALMA, CC BY 4.0 | 635 | 1.3e20 | 48 | ca. 1 | TNO |

| 49 | (28978) Ixion[31][A 12] |  | 617 | 1.2e20 | 51 | ca. 1 | TNO |

| 50 | (278361) 2007 JJ43[32][A 13] | 610 | 1.2e20 | 52 | ca. 1 | TNO |

Weitere Objekte (Auswahl)

Die nachfolgenden Objekte gehören nicht zu den 50 größten Objekten im Sonnensystem. Die Asteroiden Pallas und Vesta zählen aufgrund ihrer hohen Dichte nach heutigem Wissensstand zu den 50 massereichsten Objekten im Sonnensystem, ihr Durchmesser ist jedoch zu klein.

| Rang Ø | Name | Bild | Durchmesser (km) | Masse (kg) | Rang Masse | Dichte (g/cm³) | Objekttyp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | (2) Pallas[1][33] |  | 582 × 556 × 500 | 2.05e20 | 41 | 2,57 | Asteroid |

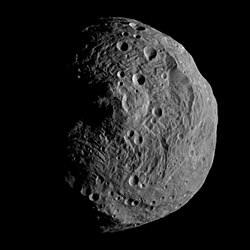

| - | (4) Vesta[1][34] |  | 569 × 555 × 458 | 2.59e20 | 40 | 3,456 | Asteroid |

| - | Enceladus[1] |  | 504 | 1.08e20 | - | 1,61 | Saturnmond |

| - | Miranda[1] | 471 | 6.6e19 | - | 1,20 | Uranusmond | |

| - | (10) Hygiea[33] |  | 530 × 407 × 370 | 9e19 | - | 2,08 | Asteroid |

| - | Proteus[1] | 440 × 416 × 404 | 5.0e19 | - | ca.1.3 | Neptunmond | |

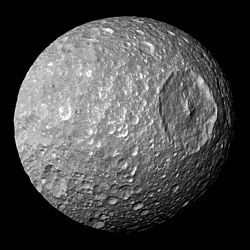

| - | Mimas[1] |  | 397 | 3.79e19 | - | 1,15 | Saturnmond |

| - | Nereid[1] |  | 340 | 3e19 | - | ca.1.5 | Neptunmond |

| - | (52) Europa[33] | 362 × 302 × 252 | 2e19 | - | 1,57 | Asteroid | |

| - | (704) Interamnia[33] | 349 × 339 × 274 | 4e19 | - | 2,29 | Asteroid | |

| - | (511) Davida[33] |  | 357 × 294 × 231 | 4e19 | - | 2,97 | Asteroid |

| - | Hyperion[1] |  | 360 × 266 × 206 | 5.6e18 | - | 0,55 | Saturnmond |

| - | (15) Eunomia[33] | 357 × 255 × 212 | 3e19 | - | 3,14 | Asteroid | |

| - | (3) Juno[1][33] |  | 320 × 267 × 200 | 2e19 | - | 3,2 | Asteroid |

Siehe auch

Anmerkungen

- ↑ Die Masse von Sedna ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 2 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2002 MS4 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 2 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2003 AZ84 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer Dichte von 0,87 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2002 AW197 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1,2 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2013 FY27 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1,2 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2004 GV9 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1,2 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2005 RN43 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1,2 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2015 RR245 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1,2 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von Varuna ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer Dichte von 0,99 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2010 RF43 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2014 UZ224 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von Ixion ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1 g/cm³

- ↑ Die Masse von 2007 JJ43 ergibt sich aus einer Abschätzung mit dem Durchmesser und einer für vergleichbar große TNO typischen angenommenen Dichte von 1 g/cm³

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj David R. Williams: Planetary Fact Sheets. Goddard Space Flight Center, abgerufen am 28. März 2020 (englisch).

- ↑ M. Brown, E. Schaller: The Mass of Dwarf Planet Eris. In: Science. Band 316, Nr. 5831, 15. Juni 2007, S. 1585, doi:10.1126/science.1139415, bibcode:2007Sci...316.1585B (hubblesite.org [PDF]).

- ↑ B. Sicardy u. a.: Size, density, albedo and atmosphere limit of dwarf planet Eris from a stellar occultation. In: EPSC Abstracts. Band 6, Oktober 2011, bibcode:2011epsc.conf..137S (copernicus.org [PDF]).

- ↑ Eris - in Depth. Abgerufen am 28. März 2020 (englisch).

- ↑ D. Ragozzine, M. E. Brown: Orbits and Masses of the Satellites of the Dwarf Planet Haumea. In: The Astronomical Journal. Band 137, Nr. 6, 2009, S. 4766–4776, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/6/4766, arxiv:0903.4213, bibcode:2009AJ....137.4766R.

- ↑ E. T. Dunham, S. J. Desch, L. Probst: Haumea's Shape, Composition, and Internal Structure. In: The Astrophysical Journal. Band 877, Nr. 1, April 2019, S. 11, doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab13b3, arxiv:1904.00522, bibcode:2019ApJ...877...41D.

- ↑ 30 verschiedene Autoren: Albedo and atmospheric constraints of dwarf planet Makemake from a stellar occultation. In: Nature. Band 491, Nr. 7425, 2012, S. 566–569, PMID 23172214, bibcode:2012Natur.491..566O. (ESO 21 November 2012 press release: Dwarf Planet Makemake Lacks Atmosphere)

- ↑ M.E. Brown: On the size, shape, and density of dwarf planet Makemake. In: The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Band 767, Nr. 1, 25. März 2013, S. L7, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/767/1/L7, arxiv:1304.1041, bibcode:2013ApJ...767L...7B.

- ↑ Alex Parker et al.: The Mass, Density, and Figure of the Kuiper Belt Dwarf Planet Makemake. In: American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #50, id.509.02. Oktober 2018, bibcode:2018DPS....5050902P.

- ↑ The mass and density of the dwarf planet (225088) 2007 OR10 author. In: Icarus. Band 334, 2019, S. 3–10, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.03.013, arxiv:1903.05439, bibcode:2018DPS....5031102K.

Initial publication at the American Astronomical Society DPS meeting #50, with the publication ID 311.02 - ↑ Braga-Ribas u. a.: The Size, Shape, Albedo, Density, and Atmospheric Limit of Transneptunian Object (50000) Quaoar from Multi-chord Stellar Occultations. In: The Astrophysical Journal. Band 773, 22. Juli 2013, S. 26, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/773/1/26, bibcode:2013ApJ...773...26B.

- ↑ Ko Arimatsu, Ryou Ohsawa, George L. Hashimoto, Seitaro Urakawa, Jun Takahashi, Miyako Tozuka: New constraint on the atmosphere of (50000) Quaoar from a stellar occultation. In: The Astronomical Journal. Band 158, Nr. 6, Dezember 2019, S. 7, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ab5058, arxiv:1910.09988, bibcode:2019AJ....158..236A.

- ↑ "TNOs are Cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region. VII. Size and surface characteristics of (90377) Sedna and 2010 EK139. In: Astronomy & Astrophysics. Band 541, 2012, S. L6, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201218874, arxiv:1204.0899, bibcode:2012A&A...541L...6P.

- ↑ a b c E. Vilenius, C. Kiss, M. Mommert: "TNOs are Cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region VI. Herschel/PACS observations and thermal modeling of 19 classical Kuiper belt objects. In: Astronomy & Astrophysics. Band 541, 2012, S. A94, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201118743, arxiv:1204.0697, bibcode:2012A&A...541A..94V.

- ↑ 1 Ceres. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, abgerufen am 12. April 2020.

- ↑ a b S. Fornasier, E. Lellouch, T. Müller, P.: TNOs are Cool: A survey of the trans-Neptunian region. VIII. Combined Herschel PACS and SPIRE observations of 9 bright targets at 70–500 µm. In: Astronomy & Astrophysics. Band 555, 2013, S. A92, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321329, arxiv:1305.0449, bibcode:2013A&A...555A..15F.

- ↑ a b Mutual Orbit Orientations of Transneptunian Binaries. In: Icarus. 2019, ISSN 0019-1035, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.03.035 (author=W. M. Grundy, K. S. Noll, H. G. Roe, M. W. Buie, S. B. Porter, A. H. Parker, D. Nesvorný, S. D. Benecchi, D. C. Stephens, C. A. Trujillo Online [PDF]).

- ↑ A. Dias-Oliveira et al.: Study of the Plutino Object (208996) 2003 AZ84 from Stellar Occultations: Size, Shape, and Topographic Features. In: The Astronomical Journal. Band 154, Nr. 1, S. 13, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa74e9, arxiv:1705.10895, bibcode:2017AJ....154...22D.

- ↑ E. Vilenius, C. Kiss, T. Müller, M. Mommert, P. Santos-Sanz, A. Pál, J. Stansberry, M. Mueller, N. Peixinho, E. Lellouch, S. Fornasier, A. Delsanti, A. Thirouin, J. L. Ortiz, R. Duffard, D. Perna, F. Henry: "TNOs are Cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region. X. Analysis of classical Kuiper belt objects from Herschel and Spitzer observations. In: Astronomy and Astrophysics. Band 564, April 2014, S. 18, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322416, arxiv:1403.6309, bibcode:2014A&A...564A..35V.

- ↑ W. M. Grundy, S. B. Porter, S. D. Benecchi, H. G. Roe, K. S. Noll, C. A. Trujillo, A. Thirouin, J. A. Stansberry, E. Barker, H. F. Levison: The mutual orbit, mass, and density of the large transneptunian binary system Varda and Ilmarë. In: Icarus. Band 257, September 2015, S. 130–138, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.04.036, arxiv:1505.00510, bibcode:2015Icar..257..130G (Online [PDF]).

- ↑ The stellar occultation by the TNO (174567) Varda of September 10, 2018: size, shape and atmospheric constraints. In: European Planetary Science Congress DPS Joint Meeting 2019. Band 13, September 2019 (Online [PDF]).

- ↑ Scott Sheppard, Yanga Fernandez, Arielle Moullet: The Albedos, Sizes, Colors and Satellites of Dwarf Planets Compared with Newly Measured Dwarf Planet 2013 FY27. In: The Astronomical Journal. Band 156, Nr. 6, 6. September 2018, S. 270, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aae92a, arxiv:1809.02184, bibcode:2018AJ....156..270S.

- ↑ M. Bannister u. a.: OSSOS: IV. Discovery of a dwarf planet candidate in the 9:2 resonance with Neptune. In: The Astronomical Journal. Band 152, Nr. 6, 23. Juli 2016, S. 212, 8, doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/6/212, arxiv:1607.06970, bibcode:2016AJ....152..212B (core.ac.uk [PDF]).

- ↑ M.E. Brown: The density of mid-sized Kuiper belt object 2002 UX25 and the formation of the dwarf planets. In: The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Band 778, Nr. 2, 2013, S. L34, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/778/2/L34, arxiv:1311.0553, bibcode:2013ApJ...778L..34B.

- ↑ E. Lellouch, R. Moreno, T. Müller, S. Fornasier, P. Sanstos-Sanz, A. Moullet, M. Gurwell, J. Stansberry, R. Leiva, B. Sicardy, B. Butler, J. Boissier: The thermal emission of Centaurs and Trans-Neptunian objects at millimeter wavelengths from ALMA observations. In: Astronomy & Astrophysics. Band 608, Dezember 2017, S. A45, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201731676, arxiv:1709.06747, bibcode:2017A&A...608A..45L.

- ↑ P. Lacerda, D. Jewitt: Densities Of Solar System Objects From Their Rotational Lightcurve. In: The Astronomical Journal. Band 133, Nr. 4, 2006, S. 1393–1408, doi:10.1086/511772, arxiv:astro-ph/0612237, bibcode:2007AJ....133.1393L.

- ↑ Ortiz, Sicardy, Camargo & Braga-Ribas: The Transneptunian Solar System. Hrsg.: Prialnik, Barucci & Young. Elsevier, 2019, Stellar Occultations by Transneptunian Objects: From Predictions to Observations and Prospects for the Future.

- ↑ W. M. Grundy, K. S. Noll, W. M. Buie, S. D. Benecchi, D. Ragozzine, H. G. Roe: The mutual orbit, mass, and density of transneptunian binary Gǃkúnǁ'hòmdímà (229762 2007 UK126). In: Icarus. Band 334, Dezember 2018, S. 30–38, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.12.037 (englisch, Online [PDF]).

- ↑ LCDB Data for (2010+RF43). Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB), abgerufen am 23. Februar 2018.

- ↑ D. W. Gerdes, M. Sako, S. Hamilton, K. Zhang, T. Khain, J. C. Becker: Discovery and Physical Characterization of a Large Scattered Disk Object at 92 AU. In: The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Band 839, Nr. 1, April 2017, S. 7, doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa64d8, arxiv:1702.00731, bibcode:2017ApJ...839L..15G.

- ↑ E. Lellouch, P. Santos-Sanz, P. Lacerda, M. Mommert, R. Duffard, J. L. Ortiz, T. G. Müller, S. Fornasier, J. Stansberry, Cs. Kiss, E. Vilenius, M. Mueller, N. Peixinho, R. Moreno, O. Groussin, A. Delsanti, A. W. Harris: "TNOs are Cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region. IX. Thermal properties of Kuiper belt objects and Centaurs from combined Herschel and Spitzer observations. In: Astronomy & Astrophysics. Band 557, September 2013, S. 19, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322047, arxiv:1202.3657, bibcode:2013A&A...557A..60L (Online [PDF]).

- ↑ A. Pál u. a.: Pushing the limits: K2 observations of the trans-Neptunian objects 2002 GV31 and (278361) 2007 JJ43. In: The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Band 804, Nr. 2, 12. Mai 2015, S. L45, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/804/2/L45, arxiv:1504.03671, bibcode:2015ApJ...804L..45P.

- ↑ a b c d e f g James Baer, Steven Chesley, Robert D. Matson: Astrometric masses of 26 asteroids and observations on asteroid porosity. In: The Astronomical Journal. Band 141, Nr. 5, 2011, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/141/5/143, bibcode:2011AJ....141..143B.

- ↑ C. T. Russell: Dawn at Vesta: Testing the Protoplanetary Paradigm. In: Science. Band 336, Nr. 6082, 2012, S. 684–686, doi:10.1126/science.1219381, PMID 22582253, bibcode:2012Sci...336..684R (Online [PDF]). phyast.pitt.edu (PDF; 713 kB)

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Photograph of Makemake taken by the Hubble Space Telescope

True color image of Ganymede, obtained by the Galileo spacecraft, with enhanced contrast.

Here is the description from JPL's web entry for PIA00716:

Natural color view of Ganymede from the Galileo spacecraft during its first encounter with the satellite. North is to the top of the picture and the sun illuminates the surface from the right. The dark areas are the older, more heavily cratered regions and the light areas are younger, tectonically deformed regions. The brownish-gray color is due to mixtures of rocky materials and ice. Bright spots are geologically recent impact craters and their ejecta. The finest details that can be discerned in this picture are about 13.4 kilometers across. The images which combine for this color image were taken beginning at Universal Time 8:46:04 UT on June 26, 1996.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA manages the mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, DC. This image and other images and data received from Galileo are posted on the World Wide Web, on the Galileo mission home page at URL http://galileo.jpl.nasa.gov. Background information and educational context for the images can be found at http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/galileo/sepo.Iapetus as seen by the Cassini probe.

Original NASA caption: Cassini captures the first high-resolution glimpse of the bright trailing hemisphere of Saturn's moon Iapetus.

This false-color mosaic shows the entire hemisphere of Iapetus (1,468 kilometers, or 912 miles across) visible from Cassini on the outbound leg of its encounter with the two-toned moon in Sept. 2007. The central longitude of the trailing hemisphere is 24 degrees to the left of the mosaic's center.

Also shown here is the complicated transition region between the dark leading and bright trailing hemispheres. This region, visible along the right side of the image, was observed in many of the images acquired by Cassini near closest approach during the encounter.

Revealed here for the first time in detail are the geologic structures that mark the trailing hemisphere. The region appears heavily cratered, particularly in the north and south polar regions. Near the top of the mosaic, numerous impact features visible in NASA Voyager 2 spacecraft images (acquired in 1981) are visible, including the craters Ogier and Charlemagne.

The most prominent topographic feature in this view, in the bottom half of the mosaic, is a 450-kilometer (280-mile) wide impact basin, one of at least nine such large basins on Iapetus. In fact, the basin overlaps an older, similar-sized impact basin to its southeast.

In many places, the dark material--thought to be composed of nitrogen-bearing organic compounds called cyanides, hydrated minerals and other carbonaceous minerals--appears to coat equator-facing slopes and crater floors. The distribution of this material and variations in the color of the bright material across the trailing hemisphere will be crucial clues to understanding the origin of Iapetus' peculiar bright-dark dual personality.

The view was acquired with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Sept. 10, 2007, at a distance of about 73,000 kilometers (45,000 miles) from Iapetus.

The color seen in this view represents an expansion of the wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum visible to human eyes. The intense reddish-brown hue of the dark material is far less pronounced in true color images. The use of enhanced color makes the reddish character of the dark material more visible than it would be to the naked eye.

This mosaic consists of 60 images covering 15 footprints across the surface of Iapetus. The view is an orthographic projection centered on 10.8 degrees south latitude, 246.5 degrees west longitude and has a resolution of 426 meters (0.26 miles) per pixel. An orthographic view is most like the view seen by a distant observer looking through a telescope.

At each footprint, a full resolution clear filter image was combined with half-resolution images taken with infrared, green and ultraviolet spectral filters (centered at 752, 568 and 338 nanometers, respectively) to create this full-resolution false color mosaic.

Dieses Bild zeigt jahreszeitliche Unterschiede in der Farbe der Atmosphäre von Saturns größtem Mond Titan mit etwas dunklerer nördlicher Hälfte und etwas hellerer südlicher Hälfte. Dieses Bild wurde im August 2009 von der NASA Sonde Cassini aufgenommen und gibt die Echtfarben wieder, entstanden aus der Kombination von Bildern mit Rot-, Grün- und Blaufiltern. Forscher haben herausgefunden dass die Winter-Hemisphäre in der Regel einen stärkeren Dunstschleier in den oberen Teilen der Atmosphäre zeigt und daher dunkler in kürzeren Wellenlängen des Lichtes (Ultraviolet bis Blau) wirkt und heller im infraroten Bereich.

Der Wechsel zwischen dunkleren und helleren Hemisphären fand über einen Zeitraum von ein bis zwei Jahren statt und hängt mit der Tag-und-Nacht-Gleiche Saturns zusammen, findet also zweimal je Saturnjahr statt. Die Grenze zwischen hellerer und dunklerer Hälfte verläuft nicht direkt am Äquator, sondern ist etwa 10 Breitengrade versetzt.

Das Bild zeigt die Seite Titans, die dem Saturn zugewandt ist. Norden ist oben, aufgenommen aus einer Entfernung von 174.000 Kilometern. Maßstab des Bildes ist etwa 10 Kilometer pro Pixel.Hubble Space Telescope image of the cubewano (90568) 2004 GV9, taken on 17 March 2010.

Saturnmond Dione, Mosaikbild von der Raumsonde Cassini, Entfernung im Bereich 27 180 bis 55 280km

Autor/Urheber: Renerpho, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Hubble image of (229762) 2007 UK126 and its satellite, taken on 2 January 2018.

From Hubble images idid01m4q, idid01m5q, idid01m6q, idid01m7q, idid01m8q, idid01m9q, idid01maq and idid01mbq (in public domain since 2 July 2018). Credit: NASA.

Hubble Space Telescope image of the cubewano (55565) 2002 AW197 on 1 December 2006.

Global mosaic of 102 Viking 1 Orbiter images of Mars taken on orbit 1,334, 22 February 1980. The images are projected into point perspective, representing what a viewer would see from a spacecraft at an altitude of 2,500 km. At center is Valles Marineris, over 3000 km long and up to 8 km deep. Note the channels running up (north) from the central and eastern portions of Valles Marineris to the area at upper right, Chryse Planitia. At left are the three Tharsis Montes and to the south is ancient, heavily impacted terrain. (Viking 1 Orbiter, MG07S078-334SP)

Some of the features in this mosaic are annotated in Wikimedia Commons.

Image of Sedna, taken by Hubble Space Telescope

Saturn planet, seen by Voyager 2.

- Original Caption Released with Image

- This true color picture was assembled from Voyager 2 Saturn images obtained Aug. 4 from a distance of 21 million kilometers (13 million miles) on the spacecraft's approach trajectory. Three of Saturn's icy moons are evident at left. They are, in order of distance from the planet: Tethys, 1,050 km. (652 mi.) in diameter; Dione, 1,120 km. (696 mi.); and Rhea, 1,530 km. (951 mi.). The shadow of Tethys appears on Saturn's southern hemisphere. A fourth satellite, Mimas, is less evident, appearing as a bright spot a quarter-inch in in from the planet's limb about half an inch above Tethys; the shadow of Mimas appears on the planet about three-quarters of an inch directly above that of Tethys. The pastel and yellow hues on the planet reveal many contrasting bright and darker bands in both hemispheres of Saturn's weather system. The Voyager project is managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

Original Caption Released with Image:

NASA's Galileo spacecraft acquired its highest resolution images of Jupiter's moon Io on 3 July 1999 during its closest pass to Io since orbit insertion in late 1995. This color mosaic uses the near-infrared, green and violet filters (slightly more than the visible range) of the spacecraft's camera and approximates what the human eye would see. Most of Io's surface has pastel colors, punctuated by black, brown, green, orange, and red units near the active volcanic centers. A false color version of the mosaic has been created to enhance the contrast of the color variations.

The improved resolution reveals small-scale color units which had not been recognized previously and which suggest that the lavas and sulfurous deposits are composed of complex mixtures (Cutout A of false color image). Some of the bright (whitish), high-latitude (near the top and bottom) deposits have an ethereal quality like a transparent covering of frost (Cutout B of false color image). Bright red areas were seen previously only as diffuse deposits. However, they are now seen to exist as both diffuse deposits and sharp linear features like fissures (Cutout C of false color image). Some volcanic centers have bright and colorful flows, perhaps due to flows of sulfur rather than silicate lava (Cutout D of false color image). In this region bright, white material can also be seen to emanate from linear rifts and cliffs.

Comparison of this image to previous Galileo images reveals many changes due to the ongoing volcanic activity.

Galileo will make two close passes of Io beginning in October of this year. Most of the high-resolution targets for these flybys are seen on the hemisphere shown here.

North is to the top of the picture and the sun illuminates the surface from almost directly behind the spacecraft. This illumination geometry is good for imaging color variations, but poor for imaging topographic shading. However, some topographic shading can be seen here due to the combination of relatively high resolution (1.3 kilometers or 0.8 miles per picture element) and the rugged topography over parts of Io. The image is centered at 0.3 degrees north latitude and 137.5 degrees west longitude. The resolution is 1.3 kilometers (0.8 miles) per picture element. The images were taken on 3 July 1999 at a range of about 130,000 kilometers (81,000 miles) by the Solid State Imaging (SSI) system on NASA's Galileo spacecraft during its twenty-first orbit.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA manages the Galileo mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, DC.

This image and other images and data received from Galileo are posted on the World Wide Web, on the Galileo mission home page at URL http://galileo.jpl.nasa.gov. Background information and educational context for the images can be found at URL http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/galileo/sepo.Uranus' icy moon Miranda is seen in this image from Voyager 2 on January 24, 1986. The Voyager project is managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Hubble Space Telescope composite image of the scattered-disc object (523794) 2015 RR245, taken on 27 October 2020. This image was created by stacking three F606W filter images to eliminate cosmic rays and artifacts.

Approximate true-color image of Ceres, using the F7 ('red'), F2 ('green') and F8 ('blue') filters, projected onto a clear filter image.

Images were acquired by Dawn at 04:13 UT May 4, 2015, at a distance of 13641 km. At the time, Dawn was over Ceres' northern hemisphere. The prominent, bright crater at right is Haulani. The smaller bright spot to its left is exposed on the floor of Oxo. Ejecta from these impacts appears to have exposed high albedo material similar to deposits found on the floor of Occator Crater.

Image Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UCLA / MPS / DLR / IDA / Justin CowartHubble Space Telescope image of the plutino 90482 Orcus and its satellite Vanth, taken on 31 October 2006.

Hubble Space Telescope image of the cubewano 2005 RN43, taken on 25 April 2010.

Bright scars on a darker surface testify to a long history of impacts on Jupiter's moon Callisto in this image of Callisto from NASA's Galileo spacecraft. The picture, taken in May 2001, is the only complete global color image of Callisto obtained by Galileo, which has been orbiting Jupiter since December 1995. Of Jupiter's four largest moons, Callisto orbits farthest from the giant planet. Callisto's surface is uniformly cratered but is not uniform in color or brightness. Scientists believe the brighter areas are mainly ice and the darker areas are highly eroded, ice-poor material.

Asteroid 4 Vesta from Dawn on July 17, 2011. The image was taken from a distance of 9,500 miles (15,000 km) away from Vesta.

Globales Farbmosaik von Triton, 1989 aufgenommen durch Voyager 2

Original Caption Released with Image: This Voyager 2 picture of Oberon is the best the spacecraft acquired of Uranus' outermost moon. The picture was taken shortly after 3:30 a.m. PST on Jan. 24, 1986, from a distance of 660,000 kilometers (410,000 miles). The color was reconstructed from images taken through the narrow-angle camera's violet, clear and green filters. The picture shows features as small as 12 km (7 mi) on the moon's surface. Clearly visible are several large impact craters in Oberon's icy surface surrounded by bright rays similar to those seen on Jupiter's moon Callisto. Quite prominent near the center of Oberon's disk is a large crater with a bright central peak and a floor partially covered with very dark material. This may be icy, carbon-rich material erupted onto the crater floor sometime after the crater formed. Another striking topographic feature is a large mountain, about 6 km (4 mi) high, peeking out on the lower left limb. The Voyager project is managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Pluto's image taken by New Horizons on July 14, 2015, from a range of 22,025 miles (35,445 kilometers). The striking features on Pluto are clearly visible, including the bright expanse of Pluto's icy, nitrogen-and-methane rich "heart," Sputnik Planitia.

The natural-looking colors result from refined calibration of data gathered by New Horizons' color Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC). The processing creates images that would approximate the colors that the human eye would perceive, bringing them closer to “true color” than the images released at the time of the encounter.

The source single-color MVIC scan includes no added data from other New Horizons imagers or instruments.With this full-disk mosaic, Cassini presents the best view yet of the south pole of Saturn's moon Tethys. The giant rift Ithaca Chasma cuts across the disk. Much of the topography seen here, including that of Ithaca Chasma, has a soft, muted appearance. It is clearly very old and has been heavily bombarded by impacts over time. Many of the fresh-appearing craters (ones with crisp relief) exhibit unusually bright crater floors. The origin of the apparent brightness (or "albedo") contrast is not known. It is possible that impacts punched through to a brighter layer underneath, or perhaps it is brighter because of different grain sizes or textures of the crater floor material in comparison to material along the crater walls and surrounding surface. The moon's high southern latitudes, seen here at the bottom, were not imaged by NASA's Voyager spacecraft during their flybys of Tethys 25 years ago. The mosaic is composed of nine images taken during Cassini's close flyby of Tethys (1,071 kilometers, or 665 miles across) on Sept. 24, 2005, during which the spacecraft passed approximately 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) above the moon's surface. This view is centered on terrain at approximately 1.2 degrees south latitude and 342 degrees west longitude on Tethys. It has been rotated so that north is up. The clear filter images in this mosaic were taken with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera at distances ranging from 71,600 kilometers (44,500 miles) to 62,400 kilometers (38,800 miles) from Tethys and at a Sun-Tethys-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 21 degrees. The image scale is 370 meters (1,200 feet) per pixel.

„Blue Marble“, die während des Fluges von Apollo 17 zum Mond am 7. Dezember 1972 entstandene Fotoaufnahme von der Erde

Autor/Urheber: Stefan Knauf, Lizenz: GPL

Maßstäbliche Darstellung der Größenverhältnisse der Planeten und der Sonne. Der Mittelpunkt der Sonne befindet sich auf dem linken Bildrand. Die Bilder der Planeten sind dem Programm Celestia entnommen. Die Saturnringe sind auf schwarzem Hintergrund dargestellt; die besonders dunklen Stellen der Ringe sind eigentlich besonders transparent bzw. Lücken in den Ringen.

Autor/Urheber: NASA / Voyager 2 / PDS / OPUS / Ardenau4, Lizenz: CC0

Neptune on 1989-08-17, taken by NASA's Voyager 2 probe. This color image was composed of three frames, orange, green, and blue, taken by Voyager 2's imaging system. This color image has been calibrated to best represent Neptune's true color and appearance. Based on: Irwin, Patrick G J (2023-12-23). "Modelling the seasonal cycle of Uranus’s colour and magnitude, and comparison with Neptune". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 527 (4): 11521–11538. DOI:10.1093/mnras/stad3761. ISSN 0035-8711.

Original Caption Released with Image: The southern hemisphere of Umbriel displays heavy cratering in this Voyager 2 image, taken Jan. 24, 1986, from a distance of 557,000 kilometers (346,000 miles). This frame, taken through the clear-filter of Voyager's narrow-angle camera, is the most detailed image of Umbriel, with a resolution of about 10 km (6 mi). Umbriel is the darkest of Uranus' larger moons and the one that appears to have experienced the lowest level of geological activity. It has a diameter of about 1,200 km (750 mi) and reflects only 16 percent of the light striking its surface; in the latter respect, Umbriel is similar to lunar highland areas. Umbriel is heavily cratered but lacks the numerous bright ray craters seen on the other large Uranian satellites; this results in a relatively uniform surface albedo (reflectivity). The prominent crater on the terminator (upper right) is about 110 km (70 mi) across and has a bright central peak. The strangest feature in this image (at top) is a curious bright ring, the most reflective area seen on Umbriel. The ring is about 140 km (90 miles) in diameter and lies near the satellite's equator. The nature of the ring is not known, although it might be a frost deposit, perhaps associated with an impact crater. Spots against the black background are due to 'noise' in the data. The Voyager project is managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Proteus ist hinter dem geheimnisvollen Triton der zweitgrößte Mond des Neptuns. Proteus wurde erst 1989 durch das Voyager 2 Raumschiff entdeckt. Das ist ungewöhnlich, da Neptun einen kleineren Mond - Nereid - hat, der schon 33 Jahre früher von der Erde aus entdeckt wurde. Der Grund für Proteus' späte Entdeckung war seine sehr dunkle Oberfläche. Auch seine Umlaufbahn ist viel näher bei Neptun als die von Nereid. Proteus hat eine ungewöhnliche kastenartige Form und wäre er nur wenig masserreicher, würde ihn seine eigene Schwerkraft in eine Kugel umformen.

Three years after NASA's New Horizons spacecraft gave humankind our first close-up views of Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, scientists are still revealing the wonders of these incredible worlds in the outer solar system. Marking the anniversary of New Horizons' historic flight through the Pluto system on July 14, 2015, mission scientists released the highest-resolution color images of Pluto and Charon.

These natural-color images result from refined calibration of data gathered by New Horizons' color Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC). The processing creates images that would approximate the colors that the human eye would perceive, bringing them closer to “true color” than the images released near the encounter.

This image was taken on July 14, 2015, from a range of 46,091 miles (74,176 kilometers). This single color MVIC scan includes no data from other New Horizons imagers or instruments added. The striking features on Charon are clearly visible, including the reddish north-polar region known as Mordor Macula.衛星ネレイド、ボイジャー2号の撮影

This true-color simulated view of Jupiter is composed of 4 images taken by NASA's Cassini spacecraft on December 7, 2000. To illustrate what Jupiter would have looked like if the cameras had a field-of-view large enough to capture the entire planet, the cylindrical map was projected onto a globe. The resolution is about 144 kilometers (89 miles) per pixel. Jupiter's moon Europa is casting the shadow on the planet.

Description from NASA :

In this view captured by NASA's Cassini spacecraft on its closest-ever flyby of Saturn's moon Mimas, large Herschel Crater dominates Mimas, making the moon look like the Death Star in the movie "Star Wars."

Herschel Crater is 130 kilometers, or 80 miles, wide and covers most of the right of this image. Scientists continue to study this impact basin and its surrounding terrain (see PIA12569 and PIA12571).

Cassini came within about 9,500 kilometers (5,900 miles) of Mimas on Feb. 13, 2010. This mosaic was created from six images taken that day in visible light with Cassini's narrow-angle camera on Feb. 13, 2010. The images were re-projected into an orthographic map projection. This view looks toward the area between the region that leads on Mimas' orbit around Saturn and the region of the moon facing away from Saturn. Mimas is 396 kilometers (246 miles) across. This view is centered on terrain at 11 degrees south latitude, 158 degrees west longitude. North is up. This view was obtained at a distance of approximately 50,000 kilometers (31,000 miles) from Mimas and at a sun-Mimas-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 17 degrees. Image scale is 240 meters (790 feet) per pixel.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging team is based at the Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://www.nasa.gov/cassini and http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org.

original description: This giant mosaic reveals Saturn's icy moon Rhea in her full, crater-scarred glory. This view consists of 21 clear-filter images and is centered at 0.4 degrees south latitude, 171 degrees west longitude.

Autor/Urheber: Renerpho, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

2013 FY27 and its satellite, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope on January 15, 2018

Autor/Urheber: ESO/P. Vernazza et al./MISTRAL algorithm (ONERA/CNRS), Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

A new SPHERE/VLT image of Hygiea, which could be the Solar System’s smallest dwarf planet yet. As an object in the main asteroid belt, Hygiea satisfies right away three of the four requirements to be classified as a dwarf planet: it orbits around the Sun, it is not a moon and, unlike a planet, it has not cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit. The final requirement is that it have enough mass that its own gravity pulls it into a roughly spherical shape. This is what VLT observations have now revealed about Hygiea. Credit: ESO/P. Vernazza et al./MISTRAL algorithm (ONERA/CNRS)

Autor/Urheber: Renerpho, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

2003 AZ84 (center) and its possible satellite

This is an image of the planet Uranus taken by the spacecraft Voyager 2 in 1986. See Uranus.jpg for how Uranus would appear in visible light.

L'asteroide 511 Davida fotografato dal Keck Observatory, dicembre 2002.

Credit: W.M. Keck Observatory

http://www2.keck.hawaii.edu/news/science/asteroid/asteroid.html

http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/multimedia/display.cfm?IM_ID=142Autor/Urheber: Renerpho, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Kuiper belt object 2002 MS4, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope on 9 April 2006.

The asteroid Juno was photographed in 2003 with a special optics system on the Hooker telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory. The researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who took the picture used varying wavelengths of light as measured in nanometers, starting with cyan and going into the infrared.

Autor/Urheber: Kevin Gill from Los Angeles, CA, United States, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Assembled using infrared, green, and ultraviolet (IR3, GRN, UV3) filtered images of Enceladus taken by Cassini on July 14 2005.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI/Kevin M. Gill(c) ALMA, CC BY 4.0

ALMA image of the faint millimeter-wavelength "glow" from the planetary body 2014 UZ224, more informally known as DeeDee. At three times the distance of Pluto from the Sun, DeeDee is the second most distant known TNO with a confirmed orbit in our solar system.

Autor/Urheber: Kevin M. Gill, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

JNCE_2022272_45C00001_V01

JNCE_2022272_45C00002_V01 JNCE_2022272_45C00003_V01 JNCE_2022272_45C00004_V01

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. GillHubble Space Telescope image of the cubewano 20000 Varuna, taken on 26 October 2005.

(c) TotoBaggins, CC BY-SA 3.0

Moons of solar system scaled to Earth's Moon.

Autor/Urheber: Renerpho, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Salacia and its moon Actaea, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope on 21 July 2006.

Autor/Urheber: Kevin M. Gill, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Processed by Kevin M. Gill, taken from data by NASA/JPL-Caltech. The original image is placed into a square black box for use in Wikipedia articles.

Image of 50000 Quaoar, taken by Hubble Space Telescope- Sum of 16 exposures registered on the KBO.

225088 Gonggong (2007 OR10) with its moon. It was the largest unnamed Solar System and Kuiper Belt object before official naming on 5 February 2020.

Haumea and its satellites, imaged on June 30, 2015 by the Hubble Space Telescope

Hubble Space Telescope image of the cubewano 174567 Varda and its satelite Ilmarë, taken on 31 August 2010.

Autor/Urheber: JorisvS (talk), Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Comparison of the five identified dwarf planets: Eris, Pluto, Makemake, Haumea, and Ceres.

Text properties for future modifications:

- Font is Verdana

- Size is 100 pt for title, 72 pt for objects, 48 pt for moons

- Color is FFFFCE

- Style is Bold

- Anti-aliasing (in Photoshop) is Sharp

Ultraviolet image of Venus's clouds as seen by the Pioneer Venus Orbiter (February 26, 1979). The immense C- or Y-shaped features which are visible only in these wavelengths are individually short lived, but reform often enough to be considered a permanent feature of Venus's clouds. The mechanism by which Venus's clouds absorb ultraviolet is not well understood.

This is a cropped bottom right image from the original four image mosaic PIA11364: Mercury's "True" Color is in the Eye of the Beholder.

Original Caption Released with Image:

Given the WAC’s ability to take images through 11 narrow-band color filters, it is natural to wonder what does Mercury look like in “true” color such as would be seen by the human eye. However, creating such a natural color view is not as simple as it may seem. Shown here are four images of Mercury. The image in the top left is the previously released grayscale monochrome single WAC filter (430-nanometer) image (PIA11245); the remaining three images are three-color composites, produced by placing the same three WAC filter images with peak sensitivities at 480, 560, and 630 nanometers in the blue, green, and red channels, respectively. The differences between the color representations result from how the brightness and contrast of each individual WAC filter image was adjusted before it was combined into a color picture. In the top right view, all of the three filter images were stretched using the same brightness and contrast settings. In the bottom left picture, the brightness and contrast of each of the three filter images were determined independent of the others. In the bottom right, the brightness and contrast settings used in the upper right version were slightly adjusted to make each of the three filter images span a similar range of brightness and contrast values.

So which color representation is “correct” for Mercury? The answer to that would indeed depend on the eye of the beholder. Every individual sees color differently; the human eye has a range of sensitivities that vary from person to person, resulting in different perceptions of “true” color. In addition, the three MDIS filter bands are narrow, and light at wavelengths between their peaks is not detected, unlike the human eye. In general, in light visible to the human eye, Mercury’s surface shows only very subtle color variations, as seen in the three images here. However, when images from all 11 WAC filters are statistically compared and contrasted, these subtle color variations can be greatly enhanced, resulting in extremely colorful representations of Mercury’s surface, such as seen in a high-resolution image of Thākur crater (PIA11365).

Date Acquired: October 6, 2008 Image Mission Elapsed Time (MET): 131775256, 131775260, 131775264, 131775268 Instrument: Wide Angle Camera (WAC) of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) Resolution: 5 kilometers/pixel (3 miles/pixel) Scale: Mercury’s diameter is 4880 kilometers (3030 miles)Spacecraft Altitude: 27,000 kilometers (17,000 miles)

Autor/Urheber: Credit: ESO/Vernazza et al., Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

VLT's SPHERE spies rocky worlds

From the description at File:Potw1749a.tif:

These images were taken by ESO's SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-Contrast Exoplanet Research) instrument, installed on the Very Large Telescope at the Paranal Observatory, Chile. These strikingly-detailed views reveal four of the millions of rocky bodies in the main asteroid belt, a ring of asteroids between Mars and Jupiter that separates the rocky inner planets of the Solar System from the gaseous and icy outer planets.

Clockwise from top left, the asteroids shown here are 29 Amphitrite, 324 Bamberga, 2 Pallas, and 89 Julia. Named after the Greek goddess Pallas Athena, 2 Pallas is about 510 kilometres wide. This makes it the third largest asteroid in the main belt and one of the biggest asteroids in the entire Solar System. It contains about 7% of the mass of the entire asteroid belt — so hefty that it was once classified as a planet. A third of the size of 2 Pallas, 89 Julia is thought to be named after St Julia of Corsica. Its stony composition led to its classification as an S-type asteroid. Another S-type asteroid is 29 Amphitrite, which was only discovered in 1854. 324 Bamberga, one of the largest C-type asteroid in the asteroid belt, was discovered even later: Johann Palisa found it in 1892. Today, it is understood that C-type asteroids may actually be bodies from the outer Solar System following the migration of the giant planets. As such, they may contain ice in their interior.

Although the asteroid belt is often portrayed in science fiction as a place of violent collisions, packed full of large rocks too dangerous for even the most skilled of space pilots to navigate, it is actually very sparse. In total, the asteroid belt contains just 4% of the mass of the Moon, with about half of this mass contained in the four largest residents: Ceres, 4 Vesta, 2 Pallas, and 10 Hygiea.Hubble Space Telescope image of the plutino 28978 Ixion, taken on 5 February 2006.