Lassa-Virus

| Lassa-Virus | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

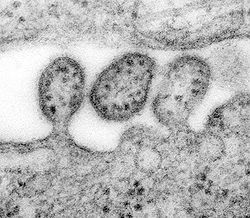

Virionen des Lassa-Virus | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systematik | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taxonomische Merkmale | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wissenschaftlicher Name | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lassa mammarenavirus | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kurzbezeichnung | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| LASV | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Links | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(B) Schemazeichnung mit Z-Protein, Glykoprotein (GP), Nukleoprotein (NP), Polymerase (L)

(C) Genomkarte der beiden Segmente L und S

Das Lassa-Virus, (wissenschaftlich Lassa mammarenavirus, LASV) Erreger des Lassa-Fiebers, ist eine Spezies (Art) behüllter einzel(−)-Strang-RNA-Viren (ss(−)RNA) der Gattung aus der Familie Arenaviridae. Wie das Lujo-Virus gehört es innerhalb dieser Gattung zur Gruppe der Altwelt-Arenaviren. Etwas weitläufiger verwandt sind Neuwelt-Arenaviren wie die Erreger des Junin-Fiebers und des Machupo-Fiebers.[3] Sie alle werden der höchsten Risikogruppe 4 zugeordnet.

Mit Stand März 2018 war das Lassa-Fieber endemisch in folgenden afrikanischen Staaten: Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Sierra Leone und Togo. Darüber hinaus wurde über Infektionen in Zentralafrikanische Republik, Senegal, und anderen afrikanischen Staaten berichtet.[4]

Entdeckung

Im Jahr 1969 erkrankte die Missions-Krankenschwester Laura Wine an einer mysteriösen Krankheit, mit welcher sie sich bei einer Patientin in der Geburtshilfe in Lassa, einem Dorf im Bundesstaat Borno, Nigeria, infizierte.[5][6][7] Sie wurde anschließend in die nigerianische Stadt Jos gebracht, wo sie verstarb. In der Folge wurden zwei weitere Personen infiziert, darunter die zweiundfünfzigjährige Krankenschwester Lily Pinneo, die sich um Laura Wine gekümmert hatte.[8] Proben aus Pinneo wurden an die Yale University in New Haven, geschickt, wo erstmals ein neues Virus, heute als Lassa mammarenavirus bezeichnet, isoliert wurde.[9] 1972 wurde festgestellt, dass die Natal-Vielzitzenmaus Mastomys natalensis das Hauptreservoir des Virus in Westafrika ist und als Überträger das Virus im Urin und im Stuhl ausscheiden kann, ohne sichtbare Symptome zu zeigen.[10][11]

Systematik

Für die folgenden drei Subtypen wurden Daten zur Genom-Sequenz in Sequenzdatenbanken hinterlegt:[12][13]

- Isolat LP – Prototy aus Nordost-Nigeria (mit dem Dorf Lassa) (‚Lineage I‘)

- Isolat 803213 – aus Süd-Nigeria (‚Lineage II‘)

- Isolat GA391 – aus Zentralnigeria (‚Lineage III‘)

- Isolat Josiah – aus Sierra Leone, Liberia und Guinea (‚Lineage IV‘)

Meldepflicht

In Deutschland ist der direkte oder indirekte Nachweis eines Lassavirus namentlich meldepflichtig nach § 7 des Infektionsschutzgesetzes, soweit der Nachweis auf eine akute Infektion hinweist. Die Meldepflicht betrifft in erster Linie die Leitungen von Laboren (§ 8 IfSG).

In der Schweiz ist der positive und negative laboranalytische Befund zu einem Lassa-Virus für Laboratorien meldepflichtig und zwar nach dem Epidemiengesetz (EpG) in Verbindung mit der Epidemienverordnung und Anhang 3 der Verordnung des EDI über die Meldung von Beobachtungen übertragbarer Krankheiten des Menschen.

Weblinks

- Lassa virus. The Universal Virus Database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTVdB)

- Replikation – Einzelsträngige (ss)-RNA-Viren, Veterinärmedizinische Universität Wien (via WebArchiv)

Einzelnachweise und Anmerkungen

- ↑ a b ICTV: ICTV Taxonomy history: Akabane orthobunyavirus, EC 51, Berlin, Germany, Juli 2019; Email ratification March 2020 (MSL #35).

- ↑ ICTV Master Species List 2018b.v2. MSL #34, März 2019.

- ↑ sowie die beiden Spezies Chapare-Virus und Tacaribe-Virus

- ↑ Travel Health Pro: Public Health England: #Lassa fever on the increase in West Africa. Auf: travelhealthpro.org.uk vom 14. März 2018.

- ↑ Ross I. Donaldson: The Lassa Ward: One Man’s Fight Against One of the World’s Deadliest Diseases. St. Martin’s Press, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-312-37700-7.

- ↑ Lassa Fever. In: www.cdc.gov. Abgerufen am 23. September 2016., Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, US Department of Health & Human Services

- ↑ J. D. Frame, J. M. Baldwin, D. J. Gocke, J. M. Troup: Lassa fever, a new virus disease of man from West Africa. I. Clinical description and pathological findings. In: The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Band 19. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, 1. Juli 1970, ISSN 0002-9637, S. 670–676, PMID 4246571.

- ↑ J. D. Frame: The story of Lassa fever. Part I: Discovering the disease. In: New York State Journal of Medicine. Band 92. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, 1. Mai 1992, ISSN 0028-7628, S. 199–202, PMID 1614671 (nih.gov).

- ↑ Sonja M. Buckley, Jordi Casals, Wilbur G. Downs: Isolation and Antigenic Characterization of Lassa Virus. In: Nature. Band 227. Jahrgang, Nr. 5254, 11. Juli 1970, S. 174, doi:10.1038/227174a0, bibcode:1970Natur.227..174B (englisch, nature.com).

- ↑ D. W. Fraser, C. C. Campbell, T. P. Monath, P. A. Goff, M. B. Gregg: Lassa fever in the Eastern Province of Sierra Leone, 1970–1972. I. Epidemiologic studies. In: The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Band 23. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 1. November 1974, ISSN 0002-9637, S. 1131–1139, PMID 4429182.

- ↑ T. P. Monath, M. Maher, J. Casals, R. E. Kissling, A. Cacciapuoti: Lassa fever in the Eastern Province of Sierra Leone, 1970–1972. II. Clinical observations and virological studies on selected hospital cases. In: The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Band 23. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 1. November 1974, ISSN 0002-9637, S. 1140–1149, PMID 4429183.

- ↑ Michael D. Bowen et al.: Genetic Diversity among Lassa Virus Strains. In: Journal of Virology. Band 74, Nr. 15, August 2000, S. 6992–7004, PMC 112216 (freier Volltext), PMID 10888638

- ↑ Deborah U. Ehichioya et al.: Current Molecular Epidemiology of Lassa Virus in Nigeria. In: Journal of Clinical Microbiology. Band 40, 2010, doi:10.1128/JCM.01891-10.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Autor/Urheber: Sarah Katharina Fehling, Frank Lennartz, and Thomas Strecker, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

Arenavirus virion structure and genome organization. (A) Electron microscopic image of Lassa virus (LASV) illustrates the common virion architecture of arenaviruses. Bar, 100nm. (B) Schematic representation of arenavirus virions. The viral envelope, a lipid bilayer derived from the host cell plasma membrane, contains multiple copies of glycoprotein spikes on the surface that are required for receptor binding and virus entry. The Z protein forms a matrix layer underneath the viral membrane. The nucleoprotein NP associates with the polymerase L to form together with the genomic RNA the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. (C) Genome organization of arenaviruses. Arenaviruses contain a bi-segmented negative-strand RNA genome, composed of the small (S) RNA segment and the large (L) RNA segment. Each RNA segment encodes two viral proteins in an ambisense orientation. The open reading frames are separated by intergenic regions.

Autor/Urheber: ViralZone, SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics: https://viralzone.expasy.org - see also permission note at File:T4likevirus virion.jpg, Lizenz: CC BY 4.0

Schemazeichnung eines Vierions der Gattung Mammarenavirus, Fam. Arenaviridae

ID#: 8699 Description: This highly magnified transmission electron micrograph (TEM) depicted some of the ultrastructural details of a number of Lassa virus virions adjacent to some cell debris. The virus, a member of the virus family Arenaviridae, is a single-stranded RNA virus, and is zoonotic, or animal-borne that can be transmitted to humans. The illness, which occurs in West Africa, was discovered in 1969 when two missionary nurses died in Nigeria, West Africa. In areas of Africa where the disease is endemic (that is, constantly present), Lassa fever is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. While Lassa fever is mild or has no observable symptoms in about 80% of people infected with the virus, the remaining 20% have a severe multisystem disease. Lassa fever is also associated with occasional epidemics, during which the case-fatality rate can reach 50%.

Signs and symptoms of Lassa fever typically occur 1-3 weeks after the patient comes into contact with the virus. These include fever, retrosternal pain (pain behind the chest wall), sore throat, back pain, cough, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, conjunctivitis, facial swelling, proteinuria (protein in the urine), and mucosal bleeding. Neurological problems have also been described, including hearing loss, tremors, and encephalitis. Because the symptoms of Lassa fever are so varied and nonspecific, clinical diagnosis is often difficult.

Approximately 15%-20% of patients hospitalized for Lassa fever die from the illness. However, overall only about 1% of infections with Lassa virus result in death. The death rates are particularly high for women in the third trimester of pregnancy, and for fetuses, about 95% of which die in the uterus of infected pregnant mothers.