La Niña

La Niña (span. ‚das Mädchen‘) ist ein Wetter, das meist im Anschluss an ein El Niño auftritt. Es ist wie dessen Gegenstück.

Mechanismus

La Niña geht mit überdurchschnittlich hohen Luftdruckunterschieden zwischen Südamerika und Indonesien (siehe Southern Oscillation) einher. Das führt zu stärkeren Passatwinden und einer allgemein verstärkten, aber abgekühlten Walker-Zirkulation. Passatwinde treiben das warme Oberflächenwasser des Pazifik verstärkt nach Südostasien. Vor der Küste Perus strömt in Folge mehr kaltes Wasser aus der Tiefe nach, das bis zu 3 °C unter der Durchschnittstemperatur liegt.

Die allgemein verstärkte, aber nun abgekühlte atmosphärische Zirkulation ist die Ursache für Telekonnektionen, die den Atlantik betreffen, denn diese Luftmassen erreichen durch die Westwinddrift in den gemäßigten Breiten den Atlantik.

Auswirkungen

Die Auswirkungen sind nicht so stark wie beim El Niño, aber La Niña hat trotzdem einen erheblichen Einfluss:

- Im Westpazifik ist das Wasser an der Oberfläche wärmer. Das hat zur Folge: Je stärker sich die Temperaturen im östlichen Teil des Pazifischen Ozeans von denen in den westlichen Gebieten unterscheiden, desto mehr Regen fällt an der australischen Nordostküste.

- In Südostasien bringt La Niña Starkregen, der Erdrutsche auslösen kann. Im zweiten Halbjahr 2010 regnete es dort so viel wie noch nie seit dem Beginn der Wetteraufzeichnungen. Die Rekordregenfälle Ende 2010 führten im nordostaustralischen Bundesstaat Queensland und im nördlichen New South Wales zu Überflutungen, deren Ausdehnung in etwa der halben Fläche des deutschen Bundeslandes Bayerns entsprachen – während im Südwesten Australiens eine extreme Dürre herrschte, wie sie noch nie zuvor beobachtet worden war.

- In Südamerika regnet es hingegen weniger und die Wüsten dörren aus.

- In Nordamerika wird das Auftreten von Hurrikanen begünstigt.

Im direkten Einflussgebiet – wenn man die Telekonnektionen unberücksichtigt lässt – treten jedoch weniger Naturkatastrophen auf als bei einem El Niño.

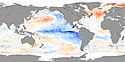

… und wie zuletzt im April 2008, wo zusätzlich eine Anomalie der Pazifischen Dekaden-Oszillation (PDO) westlich der nordamerikanischen Küste zu sehen ist.

Auffallend ist, dass die Anzahl der La-Niña-Ereignisse zwischen 1970 und ca. 1995 abgenommen und die El-Niño-Ereignisse zugenommen haben. Es kam daher die Vermutung auf, dass der anthropogene Treibhauseffekt dafür verantwortlich sei, bewiesen werden konnte das jedoch nicht, zumal sich seit Ende der 1990er Jahre der Trend deutlich umgekehrt hat und der langjährige Durchschnittswert des 20. Jahrhunderts wieder erreicht ist (Quelle: SOI-Archiv des Australischen Bureau of Meteorology). Derzeit geht man davon aus, dass diese Schwankungen größtenteils auf natürliche Schwankungen zurückzuführen sind, da sich im Pazifik in Abständen von ca. 20–30 Jahren warme und kalte Phasen, genannt Pazifische Dekaden-Oszillation (PDO) mit ihren beiden Phasen El Viejo und La Vieja, abwechseln. Der kurzfristige Einfluss der Klimaerwärmung auf derartige Klimaverteilungssysteme ist bisher vermutlich überschätzt worden; das kann sich allerdings in einigen Jahren ändern, weil diese Systeme gegenüber Veränderungen einzelner Faktoren über eine gewisse Trägheit verfügen.

Siehe auch

- El Niño-Southern Oscillation

- Southern Oscillation Index

Weblinks

- NOAA La Niña Page, Seite mit vielen Hintergründen zum La Niña-Phänomen (englisch)

- NASA Earth Observatory: La Niña Fact Sheet, Erklärung des La Niña-Phänomens (englisch)

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Autor/Urheber: unknown, Lizenz:

A cool-water anomaly known as La Niña occupied the tropical Pacific Ocean throughout 2007 and early 2008. In April 2008, scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory announced that while the La Niña was weakening, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation—a larger-scale, slower-cycling ocean pattern—had shifted to its cool phase.

This image shows the sea surface temperature anomaly in the Pacific Ocean from April 14–21, 2008. The anomaly compares the recent temperatures measured by the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer for EOS (AMSR-E) on NASA’s Aqua satellite with an average of data collected by the NOAA Pathfinder satellites from 1985–1997. Places where the Pacific was cooler than normal are blue, places where temperatures were average are white, and places where the ocean was warmer than normal are red.

The cool water anomaly in the center of the image shows the lingering effect of the year-old La Niña. However, the much broader area of cooler-than-average water off the coast of North America from Alaska (top center) to the equator is a classic feature of the cool phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). The cool waters wrap in a horseshoe shape around a core of warmer-than-average water. (In the warm phase, the pattern is reversed).

Unlike El Niño and La Niña, which may occur every 3 to 7 years and last from 6 to 18 months, the PDO can remain in the same phase for 20 to 30 years. The shift in the PDO can have significant implications for global climate, affecting Pacific and Atlantic hurricane activity, droughts and flooding around the Pacific basin, the productivity of marine ecosystems, and global land temperature patterns. “This multi-year Pacific Decadal Oscillation ‘cool’ trend can intensify La Niña or diminish El Niño impacts around the Pacific basin,” said Bill Patzert, an oceanographer and climatologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “The persistence of this large-scale pattern [in 2008] tells us there is much more than an isolated La Niña occurring in the Pacific Ocean.”

Natural, large-scale climate patterns like the PDO and El Niño-La Niña are superimposed on global warming caused by increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases and landscape changes like deforestation. According to Josh Willis, JPL oceanographer and climate scientist, “These natural climate phenomena can sometimes hide global warming caused by human activities. Or they can have the opposite effect of accentuating it.” - Caption by Rebecca LindseyThis image compares the water temperatures observed between January 25 and February 1, 2006, to long-term average conditions for that time period. The recent data were collected by the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer for EOS (AMSR-E). Red shows where sea surface temperatures are warmer than normal and blue where they are colder than normal. A large swath of the Pacific near the Equator is cooler than normal. In other words, a w:La Niña condition is in effect.

During La Niña, sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific are below average, and temperatures in the western tropical Pacific are above average. This pattern is evident in this temperature anomaly image for November 2007. This image shows the temperature for the top millimeter of the ocean’s surface—the skin temperature—for November 2007 compared to the long-term average. A strong band of blue (cool) water appears along the Equator, particularly strong near South America. Orange to red (warm) conditions appear north and south of this strong blue band. The 2007 data were collected by the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer (AMSR-E) flying on NASA’s Aqua satellite. The long-term average is based on data from a series of sensors that flew on NOAA Pathfinder satellites from 1985 to 1997.