Ise Monogatari

Das Ise Monogatari (japanisch 伊勢物語, dt. „Ise-Geschichten“) ist eine frühe romantische Erzählung (Monogatari), entstanden in der Mitte des 10. Jahrhunderts in Japan.

Überblick

Das Ise Monogatari ist eine Textsammlung aus der Mitte des 10. Jahrhunderts von rund 125 kurzen lyrischen Episoden (der Umfang reicht je nach Textvariante von 110 bis 140 Episoden), die Prosa und lyrische Elemente eines unbekannten Autors verbindet. Es ist das älteste Beispiel eines uta monogatari, also einer Sammlung kurzer Erzählungen, gestaltet um ein Gedicht oder mehrere Gedichte herum. Die Kenntnis des Ise Monogatari und des Kokinshū gehörte zum Wissen japanischer Adeliger in der späten Heian-Zeit.

Lange nahm man an, das Ise Monogatari basiere auf der Liedersammlung Narihira kashū des Dichters Ariwara no Narihira aus dem 9. Jahrhundert. Es enthält auf jeden Fall zusätzliches Material aus anderen Quellen und volkstümlichen Traditionen, die sich mit dem Text zu einem organischen Ganzen verbinden. – Die Theorie, dass Narihira der Autor ist, wird zwar nicht länger akzeptiert, aber in gewissen Maße macht der Text den Eindruck, dass er eine Art Biografie des berühmten Dichters ist, in der seine Liebesabenteuer im Mittelpunkt stehen. – Das verlässlichste Manuskript ist das mit dem Titel Den Tameie hitsuhon (伝為家筆本) im Besitz der Bibliothek der Tenri-Glaubensgemeinschaft, eine der drei Versionen, die sich von einer handschriftlichen Kopie, angefertigt von Fujiwara no Sadaie, ableiteten lassen.

Das Ise Monogatari übte einen großen Einfluss aus auf die spätere japanische Literatur. Der erste Teil des Yamato Monogatari besteht aus kurzen Geschichten um Gedichte herum, ähnlich wie beim Ise Monogatari, von dem es Material benutzte. Andere bedeutende Monogatari, die beeinflusst wurden, sind das Utsubo Monogatari, das Genji Monogatari und das Konjaku Monogatari. Auch vier Nō-Dramen sind vom Ise Monogatari inspiriert: Unrin’in (雲林院), Kakitsubata (杜若), Izutsu (井筒) und Oshio (小盬). – In der Edo-Zeit verfassten verschiedene Autoren scherzhafte Nachahmungen, wie zum Beispiel das Nise Monogatari (偽物語), also die „Imitierende Erzählung“, die Karasumaru Mitsuhiro (1579–1638) zugeschrieben wird.

Es wurden Bildrollen (emakimono) hergestellt, die verschiedene Episoden der Geschichte abbilden. Zu Beginn der Edo-Zeit erschien eine große Zahl gedruckter illustrierte Ausgaben. Ein besonders schöne Ausgabe von Bildern, die sich auf die Erzählung beziehen, wurde von Tawaraya Sotatsu hergestellt.

Aus der Handlung

Eine bekannte Szene, ein Zwischenspiel in der 9. Episode, beschreibt die Hauptfigur, unter anderem an einem achtmal zickzack-gewinkelten Steg, einer Yatsuhashi, über das berühmte Schwertlilien-Sumpfland in der Provinz Mikawa, sinnend ausruhend. Erinnerung an die verlassene Hauptstadt als Ort der Gesellschaft und Kultur, die Sehnsucht nach der verlorenen Liebe und die Schönheit der umgebenden Natur prägen diese Szene.

So ist es verständlich, dass die bildende Kunst und das Kunsthandwerk sich gerade dieser Szene in vielen Varianten angenommen hat.

Bilder

- Schreibkasten (Ogata Kōrin)

- „Schwertlilien“ (Nezu-Museum), rechter Schirm eines Stellschirm-Paares, (Kōrin)

- „Schwertlilien“ (Metropolitan Museum of Art), rechter Schirm eines Stellschirm-Paares, (Kōrin)

- Ariwara no Narihira (Yoshitoshi)

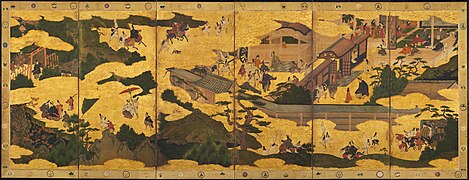

- Ise Monogatari Paravent von Matabei School c1625 Teil 1

- Ise Monogatari Paravent von Matabei School c1650 Teil 2

Literatur

- S. Noma (Hrsg.): Ise monogatari. In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha, 1993, ISBN 4-06-205938-X, S. 555

Weblinks

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Episode 9 of the Tales of Ise (伊勢物語, Ise monogatari): journeying to the East, the hero gives a poem to a hermit on mount Utsu; corresponding calligraphy by a courtier.

Autor/Urheber:

While the 11th century Tale of Genji is universally regarded as Japan's literary masterpiece, the source for visual imagery in Japanese culture is rivaled by another literary classic, the Tales of Ise. A 10th century anthology of poems interspersed with commentary, the Ise portrays the emotional and geographical journey of a courtier from the capital (Kyoto) into the countryside and beyond. The poems describe features of the natural, untamed terrain, linking them to the rather melancholy state of the traveler.

Since the Tales of Ise was—and remains today—well read by educated Japanese, a person viewing these folding screens would immediately recognize its subject, organized as a series of discrete scenes read from right to left. Neither a signature nor a seal identifies the artist, but judging from related paintings, the work can be ascribed to an artist working in Kyoto during the first quarter of the 17th century in the manner of the painter Iwasa Matabei (1578–1650). This type of historical narrative composition became quite popular around 1600 among patrons favoring a distinctly Japanese style of painting which employed rich mineral pigments and a liberal use of gold.

Irises at Yatsuhashi (right) by Ogata Kōrin (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Irises (紙本金地著色燕子花図, shihonkinjichoshoku kakitsubata zu). One of two six-section folding screens (byōbu), 150.9 x 338.8 cm each. Right screen (右隻) . Ink and color on paper with gold leaf background. Located at the Nezu Art Museum, Tokyo. Formerly held by the Nishi Honganji, Kyoto. The screen has been designated as National Treasure of Japan in the category paintings.

Autor/Urheber:

While the 11th-century Tale of Genji is universally regarded as Japan's literary masterpiece, the source for visual imagery in Japanese culture is rivaled by another literary classic, the Tales of Ise. A 10th-century anthology of poems interspersed with commentary, the Ise portrays the emotional and geographical journey of a courtier from the capital (Kyoto) into the countryside and beyond. The poems describe features of the natural, untamed terrain, linking them to the rather melancholy state of the traveler.

Since the Tales of Ise was—and remains today—well read by educated Japanese, a person viewing these folding screens would immediately recognize its subject, organized as a series of discrete scenes read from right to left. Neither a signature nor a seal identifies the artist, but judging from related paintings, the work can be ascribed to an artist working in Kyoto during the first quarter of the 17th century in the manner of the painter Iwasa Matabei (1578–1650). This type of historical narrative composition became quite popular around 1600 among patrons favoring a distinctly Japanese style of painting which employed rich mineral pigments and a liberal use of gold.