Colpoda

| Colpoda | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Colpoda inflata | ||||||||||||

| Systematik | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Wissenschaftlicher Name | ||||||||||||

| Colpoda | ||||||||||||

| O. F. Müller, 1773[1][2] |

Colpoda ist eine Gattung von Wimpertierchen aus der Klasse Colpodea, deren Ordnung Colpodida und in dieser Ordnung in der Familie Colpodidae.[3][4][5][6] Die Erstbeschreibung der Gattung Colpoda stammt vom dänischen Naturalisten Otto Friedrich Müller aus dem Jahr 1773.[1][2]

Beschreibung

Die Arten (Spezies) der Gattung Colpoda sind Einzeller von deutlich nierenförmiger Gestalt, auf einer Seite stark konvex, auf der anderen konkav. Die konkave Seite sieht oft aus, als hätte man ein Stück der Zelle abgebissen. Obwohl nicht so bekannt wie die Pantoffeltierchen (Gattung Paramecium), sind sie oft die ersten Protozoen, die in Heuaufgüssen auftauchen, vor allem wenn die Probe nicht aus einem reifen Stillgewässer (stehendem Wasser) stammt.

Etymologie

Der Gattungsname Colpoda (fem.) ist entlehnt aus dem Neulateinischen basierend auf altgriechisch κολπώδηςkolpṓdēs „umhüllend, eingebettet, gewunden“, dieses entstanden aus κόλποςkólpos „Schoß, Gewandfalte, Gebärmutter“ und dem Suffix -ειδης-eidēs „wie, von der Art“.[1]

Habitat

Die Einzeller der Gattung Colpoda sind häufig in feuchten Böden anzutreffen. Aufgrund ihrer Fähigkeit, leicht ein schützendes Zysten-Stadium einzutreten, werden sie häufig in ausgetrockneten Boden- und Pflanzenproben[7] sowie in zeitweiligen natürlichen Tümpeln (wie beispielsweise Baumhöhlen) gefunden.[8] Sie wurden auch im Darm verschiedener Tiere gefunden und können aus deren Exkrementen isoliert und kultiviert werden.[9]

Colpoda cucullus wurde auf der Oberfläche von Pflanzen gefunden und scheint dort die Mikrofauna zu dominieren. In der fleischfressenden „Kannenpflanze“ Sarracenia purpurea (Rote Schlauchpflanze) wurden mehrere Colpoda-Arten gefunden, obwohl die Flüssigkeit Protease-Verdauungsenzyme enthält.[10]

Colpoda-Wimpertierchen treten auch dort in großer Zahl auf, wo erhöhte Bakterienkonzentrationen eine reichhaltige Nahrungsquelle bieten. In kommerziellen Hühnerställen zum Beispiel scheinen sie allgegenwärtig zu sein. Die gefundenen Arten variieren stark von einem Standort zum anderen, was darauf hindeutet, dass diese Populationen lokale Boden- und Wasserpopulationen darstellen, die in den neuen Lebensraum (Habitat) eingewandert sind.[11]

Colpoda bewohnt nicht nur eine Vielzahl von Mikroklimata, sondern ist auch fast überall auf der Welt zu finden, wo es stehendes Wasser oder feuchten Boden gibt, auch dann, wenn diese Bedingungen nur vorübergehend sind. Colpoda brasiliensis wurde beispielsweise 2003 in brasilianischen Überschwemmungsgebieten entdeckt.[12] Colpoda irregularis wurde in der Hochwüstenregion im Südwesten von Idaho gefunden. Colpoda aspera wurde in der Antarktis gefunden, Colpoda-Spezies kommen auch in arktischen Regionen vor; wärmere Temperaturen und längere Sommer führen zu einer größeren Dichte und Artenvielfalt.[13]

Colpoda ist nicht nur als Gattung weit verbreitet (Kosmopolit), sondern es gibt auch mehrere Arten, die für sich nahezu weltweit verbreitet sind.[14] Obwohl Colpoda normalerweise nicht in marinen Umgebungen vorkommen, gibt es viele Möglichkeiten, wie sie von einem Kontinent zum anderen gelangen können. So können sich die Zysten beispielsweise im Gefieder von Zugvögeln festsetzen und Hunderte oder sogar Tausende von Kilometern weit verbreitet werden. Da die Zysten so klein und leicht sind, können sie sogar von Luftströmungen in die obere Atmosphäre getragen werden und dann auf einem anderen Kontinent landen.[3]

Reproduktion und Konjugation

Colpoda-Zellen teilen sich normalerweise in Zysten, aus denen zwei bis acht (meistens vier) Individuen hervorgehen. Auf diese Weise entstehen genetisch identische Individuen (Klone). Wie schnell diese Fortpflanzung erfolgt und wie sie von verschiedenen Umweltbedingungen beeinflusst wird, ist Gegenstand zahlreicher wissenschaftlicher Untersuchungen.[15][16]

In seltenen Fällen wurde beobachtet, dass sich Colpoda-Zellen in vier Individuen teilen, ohne eine Zystenwand zu bilden. Es wurde teilweise vermutet, dass unter optimalen Bedingungen die zystenlose Fortpflanzung die normale Fortpflanzungsart von Colpoda ist, und die Bildung von Zysten eine Reaktion auf ungünstige Umweltbedingungen darstellt. Die Erkenntnisse aus der langjährigen Kultivierung von Colpoda in Heuaufgüssen haben jedoch inzwischen gezeigt, dass die zystenlose Art der Fortpflanzung auch bei offenbar idealen Umweltbedingungen selten ist.[17]

Wie bei anderen Wimpertierchen kann der Teilung bei Colpoda ein sexuelles Phänomen vorausgehen, das als Konjugation bezeichnet wird. Dabei verbinden sich zwei Colpoda-Zellen an der Mundfurche und tauschen ihre DNA aus. Nach der Konjugation teilt sich die Colpoda-Zellen, wobei die DNA der beiden ursprünglichen Zellen neu verteilt wird und zahlreiche genetisch unterschiedliche Nachkommen entstehen.[18][19]

Ökologie

Die meisten Colpoda-Arten sind entweder hauptsächlich oder ausschließlich Bakterienfresser (Bakterivore). Sie ernähren sich von einer Vielzahl von Bakterien, darunter auch Moraxella-Spezies. Die Auswirkungen verschiedener bakterieller Ernährungsformen auf die Reproduktionsrate von Colpoda wurde in mehreren wissenschaftliche Studien untersucht. Auch über die ökologische Rolle, die Colpoda-Spezies im Boden spielen, gibt es zahlreiche Literatur.[20]

Außer zu ihrer Rolle als Räuber von Bakterien sind Colpoda-Spezies umgekehrt selbst Beute für eine große Vielfalt von Arten. Dazu gehören andere Protozoen, sowie kleine Tiere wie Mückenlarven[25] und andere Insektenlarven sowie Wasserflöhe.[3]

Verwendung

Aufgrund der leichten Verfügbarkeit und Kultivierbarkeit findet die Gattung Verwendung in einer Vielzahl von wissenschaftlichen Studien und auch in der Bildung. Darüber hinaus wurde Colpoda gelegentlich auch für andere praktische Zwecke vorgeschlagen. Colpoda steini könnte etwa ein Mittel zur Bewertung der Toxizität von mit Klärschlamm behandeltem Boden sein[26] und überhaupt ein Mittel zum Nachweis ganz allgemeiner chemischer Kontamination – wie nach einem Terroranschlag – sein, so ein Vorschlag.[27]

Arten

Die hier angegebene Artenliste (Stand 6. Januar 2022) folgt in erster Linie dem Taxonomy Browser des NCBI (NCBI) gelistete Arten[5] – Kennzeichnung mit hochgestelltem (N). Die wenigen im World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) gelisteten Arten[4] – Kennzeichnung mit hochgestelltem (W) – sind derzeit alle auch bei NCBI zu finden. Darüber hinaus sind noch einige weitere in der Literatur belegte Arten mit entsprechender Referenz angegeben.

- Colpoda acuta Buitkamp, 1977 – diese in Mitteleuropa vorkommende Art wurde erstmals in einer 1977 veröffentlichten Arbeit beschrieben[28]

- Colpoda aspera Kahl, 1926(N,W) – eine ziemlich kleine Art (12–42 μm), weniger nierenförmig als andere Arten; Antarktis und Subantarktis[29][30][31]

- Colpoda brasiliensis Foissner, 2003 – eine kleine Art (18–33 μm), die sich durch eine mineralische Hülle auszeichnet (ein passiver Schutz vor Räubern); benannt nach dem Land, in dem sie entdeckt wurde (Brasilien)[12]

- Colpoda cucullus O.F. Müller, 1786(N,W) deutsch Heutierchen – eine relativ weit verbreitete Art, dominantes Protozoon auf der Oberfläche von Pflanzen,[32][33][16] Größe 68 × 45 µm.[34]

- Colpoda duodenaria Taylor & Furgason, 1938 – eine kleine bis mittelgroße Art, erstmals von Charles Vincent Taylor und Waldo Furgason beschrieben[35] und im Hinblick auf die Auswirkungen verschiedener Chemikalien auf Prozess der „Widerbelebung“ der Zysten eingehend untersucht[36]

- Colpoda ecaudata (Liebmann, 1936) Foissner, Blatterer, Berger & Kohmann, 1991(N) – synonym: Cyclidium ecaudatum Liebmann, 1936

- Colpoda elliotti Bradbury & Outka, 1967(N) – eine kleine Art (15–28 μm), die aus Hirschkot kultiviert wurde[9]

- Colpoda henneguyi Fabre-Domergue, 1889(N) – eine weit verbreitete mittelgroße bis große Art (30–80 μm), dadurch ausgezeichnet, dass sie lange Zeit völlig ruhig liegen bleibt und daher leicht lebend zu fotografieren ist[37]

- Colpoda inflata Stokes, 1885(N) ([en]) – möglicherweise eine der bekanntesten und häufigsten Arten, mit einer sehr „unruhigen“ Ruhephase, in der sie sich auf engem Raum hin und her bewegt, und daher schwer zu fotografieren ist[38][39]

- Colpoda irregularis Kahl, 1931 – Diese Art zeichnet sich durch einen auffälligen postoralen (hinter der Mundöffnung befindlichen) Sack aus; sie wurde aus Moos und Bodenkruste von Felsen in der Nähe von Artemisia-Sträuchern (en. sagebrush) in Südwest-Idaho kultiviert[40]

- Colpoda lucida Greeff, 1883(N)[8]

- Colpoda magna (Gruber, 1880) Lynn, 1978(N)[8] – eine große Art (120–400 μm), deren Erscheinung bei geringerer Helligkeit durch dunkle Strukturen in der Nähe der kontraktilen Vakuole dominiert wird und oft vollständig mit Nahrungsvakuolen gefüllt ist[41]

- Colpoda maupasi Enriquez, 1908(N) – früher als Varietät von C. steini gehalten aber dann als eigene Art anerkannt; produziert üblicherweise reproduktive Zysten mit acht (bei einigen Varianten wie den Bensonhurst-Stamm auch vier) Nachkommen[42]

- Colpoda minima (Alekperov, 1985) Foissner, 1993(N)

- Colpoda parvifrons C. & L.[24] – Größe 57–70 × 30–40 µm, lebt bei Temperaturen um 21 °C[34] und wurde in der Spree bei Berlin gefunden; die kontraktile Vakuole ist posterior gelegen, aber nicht genau endständig wie bei C. cucullus[23]

- Colpoda simulans Kahl, 1931 – eine mittelgroße Art mit der klassischen „angebissenen“ (en. bite taken out of it) Colpoda-Form[43]

- Colpoda spiralis Novotny, Lynn & Evans, 1977(N)[8] – eine sehr ungewöhnliche Art mit einem großen Überhang, der ihr ein fast schneckenhausartiges Aussehen verleiht; erstmals in Arizona gefunden,[8] dann in New Mexico und Nevada, möglicherweise in Nordkalifornien[44]

- Colpoda steini Maupas, 1883(N,W) – mit Schreibvariante C. steinii; eine weit verbreitete kleine bis mittelgroße Art (14–60 μm), in der Regel freilebend, kann aber auch an Landschnecken parasitieren[45]

- Colpoda sp. CBOLN070-08(N)

- Colpoda sp. CO_31d(N)

- Colpoda sp. LH20100323B12(N)

- Colpoda sp. MD-2011(N)

- Colpoda sp. PRA-118(N)

- Colpoda sp. RR(N)

- Colpoda sp. Sr_ci_Cp01(N)

Photogalerie

Wimpertierchen (Colpoda sp.) und Zwiebelhaut

C. cucullus und Monas guttula

C. cucullus

C. steini mit Kristallen

C. cf. spiralis aus Heu

Ebenfalls C. cf. spiralis aus Heu

Vierzellige Teilungscyste eines Bodenciliaten der Gattung Colpoda

Entwicklungsstadien von C. cucullus

Videos

Für eine Vollansicht vor dem Abspielen auf die Bilder klicken (wenn bereits auf Play gedrückt, erneutes Laden mit (F5)).

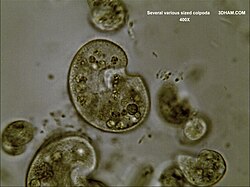

Mehrere Dutzend verschieden große Colpoda-Zellen (mindestens 3 Arten repräsentierend), zusammen mit anderen Wimpertierchen

Große Colpoda-Zelle unter vielen kleineren und anderen Wimpertierchen

Detailvideo von Colpoda im Ruhestadium

Ein weiteres Colpoda-Individuum im Ruhestadium, die die relative Größe zeigend

Ungewöhnliche Colpoda, möglicherweise Colpoda spiralis

Ebenfalls ungewöhnliche Colpoda, evtl. Colpoda spiralis, aus der Zeit, als diese entdeckt wurde.

Sehr viele Colpoda-Zellen, die anscheinend an Debris (ogan. Abfall) festsitzen

Eine aktive Colpoda-Zelle scheint eine ruhende zu „belästigen“

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b c History and Etymology for Colpoda, Merriam-Webster

- ↑ a b Otto Friedrich Müller: Vermium terrestrium et fluviatilium, seu, Animalium infusoriorum, helminthicorum et testaceorum … succincta historia, Band 1, Nr. 1, Kopenhagen & Leipzig, 1773, S. 58

- ↑ a b c Denis Lynn: The Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature. 3. Auflage. Springer Netherlands, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4020-8238-2, S. 605 (englisch, Google Books). Siehe insbes:Auch: Abstract. Springer Science & Business Media, New York, ISBN 978-1-4020-8239-9.

- ↑ a b WoRMS: Colpoda O.F. Müller, 1773. Bitte die Schalter „marine only“ (und „extant only“) deaktivieren.

- ↑ a b NCBI: Colpoda (genus); graphisch: Colpoda, auf: Lifemap NCBI Version

- ↑ OneZoom: Colpoda

- ↑ Rosemarie Arbur: Colpoda encystment: The Short, Happy Life of. In: Microscopy UK. Abgerufen am 6. Januar 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ a b c d e NIES: Colpoda O. F. Muller, 1773. (englisch). National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan.

- ↑ a b P. C. Bradbury, D. E. Outka: The Structure of Colpoda elliotti n. sp. In: The Journal of Protozoology. Band 14, Nr. 2, Mai 1967, ISSN 1550-7408, S. 344–348, doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1967.tb02006.x, PMID 4962571 (englisch). Epub 30. April 2007, Abstract (Memento im Webarchiv vom 5. Januar 2013).

- ↑ R. W. Hegner: The Protozoa of the Pitcher Plant, Sarracenia purpurea. In: The Biological Bulletin, Band 50, Nr. 3, 1. März 1926. The University of Chicago Press, Published in association with the Marine Biological Laboratory. S. 271–278, doi:10.2307/1536674.

- ↑ Julie Baré, Koen Sabbe, Jeroen Van Wichelen, Ineke van Gremberghe, Sofie D'hondt, Kurt Houf: Diversity and Habitat Specificity of Free-Living Protozoa in Commercial Poultry Houses. In: Applied and Environmental Microbiology. Band 75, Nr. 5, März 2009, ISSN 0099-2240, S. 1417–1426, doi:10.1128/AEM.02346-08, PMID 19124593, PMC 2648169 (freier Volltext), bibcode:2009ApEnM..75.1417B (englisch).

- ↑ a b Wilhelm Foissner: Pseudomaryna australiensis nov. gen., nov. spec. and Colpoda brasiliensis nov. spec., two new colpodids (Ciliophora, Colpodea) with a mineral envelope. In: European Journal of Protistology. Band 39, Nr. 2, Januar 2003, S. 199–212. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00909, Semantic Scholar.

- ↑ H. G. Smith: The Temperature Relations And Bi-Polar Biogeography of the Ciliate Genus Colpda. In: British Antarctic Survey Bulletin, Nr. 37, 1973, S. 7–13. Memento im Webarchiv vom 18. Mai 2013.

- ↑ Bland J. Finlay, Genoveva F. Esteban, Ken J. Clarke, José L. Olmo: Biodiversity of Terrestrial Protozoa Appears Homogeneous across Local and Global Spatial Scales. In: Protist. Band 152, Nr. 4, Dezember 2001, S. 355–366, doi:10.1078/1434-4610-00073, PMID 11822663 (Online).

- ↑ Donald Ward Cutler, Lettice May Crump: The Rate of Reproduction in Artificial Culture of Colpidium colpoda. Part III. In: Biochemical Journal. Band 18, Nr. 5, Januar 1924, ISSN 0264-6021, S. 905–912, doi:10.1042/bj0180905, PMID 16743371, PMC 1259465 (freier Volltext) – (Online).

- ↑ a b Tom Goodey: The excystation of colpoda cucullus from its resting cysts, and the nature and properties of the cyst membranes. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Band 86, Nr. 589, 12. Juni 1913, doi:10.1098/rspb.1913.0041

- ↑ C. A. Stuart, G. W. Kidder, A. M. Griffin: Growth Studies on Ciliates. III. Experimental Alteration of the Method of Reproduction in Colpoda. In: Physiological Zoology. Band 12, Nr. 4, Oktober 1939, ISSN 0031-935X, S. 348–362, doi:10.1086/physzool.12.4.30151513. JSTOR:30151513

- ↑ UCMP: Ciliata: Life History and Ecology. In: www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Abgerufen am 6. Januar 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ George W. Kidder, Clarence Lloyd Claff: Cytological Investigations of Colpoda cucullus. In: The Biological Bulletin, Band 74, Nr. 2, April 1938, S. 178–197, ISSN 0006-3185, doi:10.2307/1537753, JSTOR:1537753.

- ↑ Jan Dirk Elsas, Jack T. Trevors, Elizabeth M. H. Wellington: Modern Soil Microbiology. Taylor & Francis, 1997, ISBN 978-0-8493-9034-0, S. 708 (Google Books).

- ↑ NIES: Sphaerophrya Claparede & Lachmann, 1859

- ↑ WoRMS: Suctoria Claparède & Lachmann, 1858 (subclass)

- ↑ a b W. Saville Kent: A Manual of the Infusoria: Including a Description of all Known Flagellate, Ciliate, And Tentaculiferous Protozoa, British And Foreign,And an Account of the Organization And Affinities of the Sponges. Band 2, David Bogue, London 1881–1882; insbes. S. 513

- ↑ a b Encyclopædia Britannica: Infusoria, 1911; Fig. viii. – Suctoria

- ↑ D. Liane Cochran-Stafira, Carl N. von Ende: Integrating Bacteria into Food Webs: Studies Withsarracenia Purpureainquilines. In: Ecology. Band 79, Nr. 3, 1. April 1998, S. 880–898, doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[0880:IBIFWS]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Colin D. Campbell, Alan Warren, Clare M. Cameron, Susan J. Hope:

- Use of Colpoda steinii to bioassay the toxicity and bioavailability of heavy metals in a long term sewage sludge-treated soil. British Section of the Society of Protistologists (formerly Society of Protozoologists), Annual Meeting, Liverpool, 27.–29. März 1995.

- Direct toxicity assessment of two soils amended with sewage sludge contaminated with heavy metals using a protozoan (Colpoda steinii) bioassay. In: Chemosphere, Band 34, 1997, S. 501–514, doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(96)00389-X.

- ↑ L. I. Pozdnyakova, V. P. Lozitsky, A. S. Fedchuk, I. N. Grigorasheva, Y. A. Boshchenko, T. L. Gridina, S. V. Pozdnyakov: Medical Treatment of Intoxications and Decontamination of Chemical Agent in the Area of Terrorist Attack. Kapitel: Biological Method for the Water, Food, Fodders and Environment Toxic Chemical Materials Contamination Indication. In: NATO Security Through Science Series. Band 1. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2006, ISBN 978-1-4020-4168-6, S. 225–230, doi:10.1007/1-4020-4170-5_26 (englisch).

- ↑ Ulrich Buitkamp: Uber die Ciliatenfauna zweier mitteleuropaischer Bodenstandorte (Protozoa; Ciliata). In: Decheniana (Bonn), Band 130, 1977, S. 114–126, Abstract bei NIES Ref ID: 2365.

- ↑ AADC: Taxon Profile: Colpoda aspera, auf: Australian Antarctic Data Centre, Biodiversity database.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petz, Wilhelm Foissner: Morphology and infraciliature of some soil ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) from continental Antarctica, with notes on the morphogenesis of Sterkiella histriomuscorum, In: Polar Record, Band 33, Nr. 187, Cambridge University Press, 27. Oktober 2009, S. 307–326, doi:10.1017/S0032247400025407

- ↑ EOL: Colpoda aspera. In: eol.org. Abgerufen am 6. Januar 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Stuart S. Bamforth: Population Dynamics of Soil and Vegetation Protozoa. In: Integrative and Comparative Biology. Band 13, Nr. 1, Februar 1973, ISSN 1540-7063, S. 171–176, doi:10.1093/icb/13.1.171 (englisch, Online). Epub 1. August 2015.

- ↑ S. Lindow; Mark J. Bailey, A. K. Lilley, T. M. Timms-Wilson; P. T. N. Spencer-Phillips: Phyllosphere Microbiology: A Perspective. CABI, 2006, ISBN 978-1-84593-178-0, S. 1–12 (englisch, Google Books). Siehe insbes. S. 12.

- ↑ a b W. E. Bullington: A Study of Spiral Movement in the Ciliate Infusoria. In: Archiv für Protistenkunde, Band 50, 1925, S. 219–274; insbes. Tafel 12 List of Ciliates studied. S. 266

- ↑ C. H. Danforth: Biographical Memoir of Charles Vincent Taylor (1885–1946). XXV, Nr. 8. National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 1947 (Online [PDF; abgerufen am 7. Januar 2022]). Memento im Web-Archiv vom 7. Juni 2011.

- ↑ Saori Tsutsumi, Tomoko Watoh, Koji Kumamoto, Hiyoshizo Kotsuki, Tatsuomi Matsuola: Effects of porphyrins on encystment and excystment in ciliated protozoan Colpoda sp.. In: Jpn. J. Protozool., Band 37, Nr. 2, 2004-06-13, S. 119–126,PDF.

- ↑ EOL: Colpoda henneguyi. In: eol.org. Abgerufen am 6. Januar 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ EOL: Colpoda inflata. In: eol.org. Abgerufen am 6. Januar 2022 (englisch).

- Suche nach Colpoda inflata.

- Colpoda inflata Stokes, 1885. Memento im Webarchiv vom 7. Mai 2011.

- ↑ K. Bhaskaran, A. V. Nadaraja, M. V. Balakrishnan, A. Haridas: Dynamics of sustainable grazing fauna and effect on performance of gas biofilter. In: J. Biosci. Bioeng. Band 105, Nr. 3, März 2008, S. 192–197, doi:10.1263/jbb.105.192, PMID 18397767 (Online).

- ↑ micro*scope: Colpoda irregularis. Archiviert vom am 18. Juli 2011; abgerufen am 7. Januar 2022 (englisch). Info: Der Archivlink wurde automatisch eingesetzt und noch nicht geprüft. Bitte prüfe Original- und Archivlink gemäß Anleitung und entferne dann diesen Hinweis. Memento im Webarchiv vom 25. Februar 2012.

- ↑ EOL: Colpoda magna. In: eol.org. Abgerufen am 6. Januar 2022 (englisch).

- Suche nach Colpoda magna.

- Colpoda magna. Memento im Webarchiv vom 30. Dezember 2019.

- ↑ Morton Padnos, Sophie Jakowska, Ross F. Nigrelli: Morphology and Life History of Colpoda maupasi, Bensonhurst Strain. In: The Journal of Protozoology. Band 1, Nr. 2, Mai 1954, ISSN 0022-3921, S. 131–139, doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1954.tb00805.x (englisch). Abstract (Memento im Webarchiv vom 22. März 2014).

- ↑ Protist Images: Colpoda simulans Kahl, 1931. Auf: hosei.ac.jp, abgerufen am 6. Januar 2022

- ↑ Colpoda Spiralis ?, on 3dham.com — Colpoda cf. spiralis, gefunden in Nordkalifornien

- ↑ Bruce D. Reynolds: Colpoda steini, a Facultative Parasite of the Land Slug, Agriolimax agrestis. In: The Journal of Parasitology, Band 22, Nr. 1, The American Society of Parasitologists, Allen Press, Februar 1936, S. 48–53, doi:10.2307/3271896, JSTOR:3271896.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

I am tentatively identifying this species as Colpoda spiralis. This comes from a hay

infusion made by tossing some grass (including some soil clinging to the roots) and a few stray pine needles into the plastic top of a "cake box" container (from a pack of 25 DVDRs) and then adding tap water than had set for a couple of weeks. The culture was started May 27 and on June 3 several members of this species suddenly appeared.

In previous hay infusions based on samples from this same location (95841) several species of colpoda had been observed but none that even remotely resembled this. I must admit that I don't fully understand all the terms used in description of colpoda http://www.nies.go.jp/chiiki1/protoz/morpho/colpoda.htm and it is difficult to fully describe a species based solely on observations through a light microscope. Additionally, I haven't found any pictures of Colpoda Spiralis (a picture is worth a thousand words!) However, the defning feature described for Colpoda spriralis certainly seems to be present in this species!

If this is Colpoda sprialis then this is, as far as I can tell, the first time is has been reported in CA and northern CA at that. Also, it was not in the usual "tree hole"

habitat.Autor/Urheber: Dr. Eugen Lehle, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Colpoda inflata mit zahlreichen Nahrungsvakuolen

Autor/Urheber: Picturepest, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Ciliat (Colpoda) und Zwiebelhaut

Autor/Urheber: Internet Archive Book Images, Lizenz: No restrictions

Identifier: generalphysiolo00verw (find matches)

Title: General physiology; an outline of the science of life

Year: 1899 (1890s)

Authors: Verworn, Max, 1863-1921 Lee, Frederic S. (Frederic Schiller), 1859-1939, ed. and tr

Subjects: Physiology

Publisher: London, Macmillan and co., limited New York, The Macmillan company

Contributing Library: Columbia University Libraries

Digitizing Sponsor: Open Knowledge Commons

View Book Page: Book Viewer

About This Book: Catalog Entry

View All Images: All Images From Book

Click here to view book online to see this illustration in context in a browseable online version of this book.

Text Appearing Before Image:

th simple growth. AnAmoeba changes simply by increasing in mass and then dividing.The halves then grow again until they become so large that theyagain divide. The whole developmental cycle of Amoeba consistsin growth up to cell-division. We see, therefore, that growth and ELEMENTARY VITAL PHENOMENA 205 cell-division are the simplest elements that development demands ; in fact, in the whole living world there is no development withoutgrowth and cell-division. In all Protista that reproduce by spore-formation, there occurs a development expressing itself in com-plex changes of form. In this case the spores, which are totallyunlike the mother-cell, must pass through a series of changes ofform until they become like it. The development of the Protistahas been little studied. Nevertheless, Khumbler (88) hasfollowed completely and with great care that of the infusoriangenus Colpoda. Colpoda is a small bean-shaped infusorian, thesurface of whose whole body is ciliated (Fig. 84, A). In spore-

Text Appearing After Image:

Fig. S4.—Development of Colpoda cucullus. (After Rhumbler.) formation the body surrounds itself with a thick envelope orcyst (B), within which by giving off water the body constantlydiminishes its volume. Finally it extrudes all undigested food-particles and draws itself together into a ball (C), which loses itscilia and surrounds itself by a second smaller envelope (D). Thecontents of this second envelope (E) break up into single spores,which together with a remnant consisting of useless materialburst the capsule and freely wander out (E). From each spore (G)a new individual develops by the spore transforming itself into asmall amoeba-like being which creeps about, takes food, grows(H, J, K, L), develops a long flagellum with which it swims (31),and finally contracts into a small spherical cell (A7), which coversits surface with cilia (0), and by further growth gradually assumesthe form of a Colpoda (P, Q, P). Thus the developmental cycle iscompleted. 206 GENEHAL PHYSIOLOGY That wh

Note About Images

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Several dozen colpoda of various sizes representing at least 3 species accompanied by other small ciliates and vorticella. Magnified 100 times

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Active colpoda seems to harass a resting colpoda Magnified 400 times

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Several colpoda seemily stuck to some debris Magnified 100 times

Autor/Urheber: Picturepest, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Colpoda cucullus & Monas guttula - 400x

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Very detailed video of colpoda Magnified 400 times

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

I am tentatively identifying this species as Colpoda spiralis. This comes from a hay

infusion made by tossing some grass (including some soil clinging to the roots) and a few stray pine needles into the plastic top of a "cake box" container (from a pack of 25 DVDRs) and then adding tap water than had set for a couple of weeks. The culture was started May 27 and on June 3 several members of this species suddenly appeared.

In previous hay infusions based on samples from this same location (95841) several species of colpoda had been observed but none that even remotely resembled this. I must admit that I don't fully understand all the terms used in description of colpoda http://www.nies.go.jp/chiiki1/protoz/morpho/colpoda.htm and it is difficult to fully describe a species based solely on observations through a light microscope. Additionally, I haven't found any pictures of Colpoda Spiralis (a picture is worth a thousand words!) However, the defning feature described for Colpoda spriralis certainly seems to be present in this species!

If this is COlpoda sprialis then this is, as far as I can tell, the first time is has been reported in CA and northern CA at that. Also, it was not in the usual "tree hole"

habitat.Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Very detailed video of colpoda Magnified 400 times

Autor/Urheber: Dr. Eugen Lehle, Lizenz: CC BY 3.0

Konjugation beim Ciliaten Colpoda cucullus (Heutierchen)

Autor/Urheber: Dr. Eugen Lehle, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Vierzellige Teilungscyste eines Bodenciliaten der Gattung Colpoda

Sphaerophrya magna, Maupas (Suctoria). It has seized with its tentacles, and is in the act of sucking out the juices of six examples of the Ciliate Colpoda parvifrons C. & L. — References.:

- W. Saville Kent: Manual of the Infusoria

- Sphaerophrya Claparede & Lachmann, 1859, National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES), Japan

- Suctoria Claparède & Lachmann, 1858 (subclass), World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS)

- Sphaerophrya Claparède & Lachmann, 1860, Global Biodiversity Information Facilit (GBIF)

- Genus Sphaerophrya Claparède & Lachmann, 1859, The Taxonomicon

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Measurements of typical large colpoda @ 400X

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

I am tentatively identifying this species as Colpoda spiralis. This comes from a hay

infusion made by tossing some grass (including some soil clinging to the roots) and a few stray pine needles into the plastic top of a "cake box" container (from a pack of 25 DVDRs) and then adding tap water than had set for a couple of weeks. The culture was started May 27 and on June 3 several members of this species suddenly appeared.

In previous hay infusions based on samples from this same location (95841) several species of colpoda had been observed but none that even remotely resembled this. I must admit that I don't fully understand all the terms used in description of colpoda http://www.nies.go.jp/chiiki1/protoz/morpho/colpoda.htm and it is difficult to fully describe a species based solely on observations through a light microscope. Additionally, I haven't found any pictures of Colpoda Spiralis (a picture is worth a thousand words!) However, the defning feature described for Colpoda spriralis certainly seems to be present in this species!

If this is COlpoda sprialis then this is, as far as I can tell, the first time is has been reported in CA and northern CA at that. Also, it was not in the usual "tree hole"

habitat.Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Several colpoda, various sizes Magnified 400 times

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Big colpoda amongst many smaller oners. Magnified 100 times

Autor/Urheber: Picturepest, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Colpoda cucullus - 400x

Autor/Urheber: John Alan Elson, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

I am tentatively identifying this species as Colpoda spiralis. This comes from a hay

infusion made by tossing some grass (including some soil clinging to the roots) and a few stray pine needles into the plastic top of a "cake box" container (from a pack of 25 DVDRs) and then adding tap water than had set for a couple of weeks. The culture was started May 27 and on June 3 several members of this species suddenly appeared.

In previous hay infusions based on samples from this same location (95841) several species of colpoda had been observed but none that even remotely resembled this. I must admit that I don't fully understand all the terms used in description of colpoda http://www.nies.go.jp/chiiki1/protoz/morpho/colpoda.htm and it is difficult to fully describe a species based solely on observations through a light microscope. Additionally, I haven't found any pictures of Colpoda Spiralis (a picture is worth a thousand words!) However, the defning feature described for Colpoda spriralis certainly seems to be present in this species!

If this is Colpoda sprialis then this is, as far as I can tell, the first time is has been reported in CA and northern CA at that. Also, it was not in the usual "tree hole"

habitat. This video is from when I first spotted this speciesAutor/Urheber: Picturepest, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Colpoda steinii Kristalle - 400x - 15my