Caldera (Krater)

Eine Caldera (spanisch caldera ‚Kessel‘) ist eine kesselförmige Vertiefung der Planetenoberfläche, die vulkanischen Ursprungs ist. Je nach Art ihrer Entstehung können zwei Typen von Calderen, Explosionscaldera und Einsturzcaldera, unterschieden werden. Mit einem Durchmesser von 1 bis 100 km ist eine Caldera deutlich größer als ein Vulkankrater. Die Entstehung einer Caldera ist ein seltener Prozess, der zwischen 1900 und 2018 nur achtmal dokumentiert wurde.

Namenskunde

Leopold von Buch führte in seinem 1825 erschienenen Buch Physicalische Beschreibung Der Canarischen Inseln den Begriff Caldera in die Geologie ein. Nach Untersuchungen in Frankreich, Italien und den Kanarischen Inseln, wo er die Caldera de las Cañadas auf Teneriffa und die Caldera de Taburiente auf La Palma besuchte, entwickelte er die Theorie der Erhebungskrater. Nach seiner, heute nicht mehr gültigen, Theorie wird eine Caldera von erdinneren Kräften verursacht, die zu einer Hebung und blasenförmigen Wölbung der Erdkruste führt, bis diese radial aufbricht.[1]

Entstehung

Calderen entstehen entweder durch explosive Eruptionen (Sprengtrichter)[2] oder durch den Einsturz oberflächennaher Magmakammern eines Zentralvulkans, die zuvor durch Ausbrüche entleert worden sind. Explosionscalderen und Einsturzcalderen sind oft schwer voneinander zu unterscheiden, zumal der Boden einer jungen Caldera oft durch ausströmende Lava überdeckt wird. Nachdem die Lava abgekühlt ist, füllen sich tiefliegende Calderen häufig mit Wasser und bilden dann einen Calderasee.

Calderen von Supervulkanen können gewaltige Ausmaße annehmen. So war die Caldera des ersten Yellowstone-Vulkanausbruchs 80 Kilometer lang und 55 Kilometer breit.

Ist der Vulkan weiterhin aktiv, können sich auf dem Boden einer Caldera erneut Vulkankegel bilden, wie es beispielsweise beim Vesuv oder der Aira-Caldera geschehen ist. Diese Entstehung eines Vulkans auf einem alten Vulkan bezeichnet man als Somma-Vulkan.

Auch Calderen in Calderen werden beobachtet, etwa die Halemaʻumaʻu-Caldera am Boden der Kīlauea-Caldera.

Abgrenzung

Genetisch und/oder morphologisch den Calderen ähnliche, aber nicht identische und deshalb anders bezeichnete Oberflächenformen sind:

- Maare, die durch vulkanische Dampfexplosionen (phreatomagmatische Explosionen) entstehen und in der Regel kleiner sind als Calderen,

- Vulkankrater, die den Austrittspunkt von Magma bezeichnen und ebenfalls kleiner sind als Calderen und

- Kare, kesselförmige Täler, die von einem Gletscher ausgeschürft wurden.

Häufigkeit

Die Entstehung einer Caldera ist ein seltener Prozess, der zwischen 1900 und 2018 nur achtmal dokumentiert wurde. Die Entstehung der Calderen von Mount Katmai 1912 und Pinatubo 1991 fand nach explosiven Eruptionen statt, wobei letztere eine der größten Eruptionen des 20. Jahrhunderts war. Die Calderen von La Cumbre 1968, Tolbatschik in 1975–76, Miyake-jima 2000 und Piton de la Fournaise 2007 sind auf Effusive Eruptionen zurückzuführen. Der Kollaps des Bárðarbunga fand 2015 statt.[3] Die Absenkungen der Caldera um den Krater Halemaʻumaʻu konnte 2018 beobachtet werden.

Bekannte Calderen

Zu den bedeutendsten Calderen gehören die des Teide (Teneriffa), der Tobasee (Sumatra), die Yellowstone-Caldera (USA), die Caldera der Inselgruppe Santorin (Griechenland) und die des Deception Islands (Chile).

Die Caldera de Taburiente (La Palma), die ursprünglich namensgebend war, ist geologisch betrachtet vermutlich keine Caldera, sondern durch spätere Erosion entstanden.

- Afrika

- Las Cañadas auf Teide (Teneriffa, Spanien, Kanarische Inseln, gehört geographisch zu Afrika)

- Pico do Fogo (Fogo, Kap Verde)

- Ngorongoro (Tansania)

- Trou au Natron (Tschad)

- Waw an-Namus (Libyen)

- Asien

- Aira-Caldera (Präfektur Kagoshima, Japan)

- Aso (Präfektur Kumamoto, Japan)

- Batur (Bali, Indonesien)

- Bromo (Java, Indonesien)

- Kikai-Caldera (Präfektur Kagoshima, Japan)

- Krakatau, Indonesien

- Kurilensee (Kamtschatka, Russland)

- Nemrut (Türkei)

- Pinatubo (Luzon, Philippinen)

- Rinjani (Lombok, Indonesien)

- Taal (Luzon, Philippinen)

- Tobasee (Sumatra, Indonesien)

- Tambora (Sumbawa, Indonesien)

- Tao-Rusyr-Caldera (Onekotan, Russland)

- Towada (Präfektur Aomori, Japan)

- Tazawa (Präfektur Akita, Japan)

- Yankicha/Uschischir (Kurilen, Russland)

- Amerika

- Nordamerika

- Mount Aniakchak (Alaska, USA)

- Crater Lake (Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, USA)

- Kīlauea (Hawaii, USA, liegt geographisch im Polynesischen Dreieck und gehört zur Pazifischen Platte)

- Mokuʻāweoweo-Caldera auf Mauna Loa (Hawaii, USA, liegt geographisch im Polynesischen Dreieck und gehört zur Pazifischen Platte)

- Mount Katmai (Alaska, USA)

- La-Garita-Caldera (Colorado, USA)

- Long Valley (Kalifornien, USA)

- Newberry Caldera (Oregon, USA)

- Mount Okmok (Alaska, USA)

- Valles-Caldera (New Mexico, USA)

- Yellowstone (Wyoming, USA)

- Mittelamerika

- Masaya, Nicaragua

- Lago de Atitlán, Guatemala

- Südamerika

- Cuicocha, Ecuador

- Vilama, Argentinien

- Caldera del Atuel, Argentinien

- Nordamerika

- Europa

- Askja (Island)

- Bárðarbunga (Island)

- Krafla (Island)

- Katla (Island)

- Campi Flegrei (Italien)

- Bolsenasee (Italien)

- Braccianosee (Italien)

- Laacher See (Vulkaneifel, Deutschland)

- Santorin (Griechenland)

- Lagoa do Fogo, auf Sao Miguel (Azoren, Portugal)

- Cabeço Gordo, auf Faial (Azoren, Portugal)

- Scafell Caldera (Großbritannien)

- Ozeanien

- Taupō (Neuseeland)

- Mount Warning (Australien)

- Blue Lake (Süd-Australien)

- Ambrym (Vanuatu)

- Kuwae (Vanuatu)

Außerirdische Calderen

Auf verschiedenen Himmelskörpern des Sonnensystems, die einen vergangenen oder rezenten Vulkanismus aufweisen, konnten auf von Raumsonden gewonnenen Aufnahmen Caldera-Strukturen entdeckt werden, die zum Teil deutlich größer sind als irdische Calderen. Auf dem vulkanisch aktiven Jupitermond Io wurden hunderte Calderen entdeckt, die einen Durchmesser von bis zu 400 km aufweisen.

- Mars

- Caldera des Olympus Mons

- Venus

- Caldera des Maat Mons

- Io

- Prometheus-Caldera

Siehe auch

Literatur

- J. W. Cole, D. M. Milner, K. D. Spinks: Calderas and caldera structures: a review. In: Earth-Science Reviews. Band 69, Nr. 1, 2005, S. 1–26, doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2004.06.004 (englisch).

- Agust Gudmundsson: Caldera Volcanism: Analysis, Modelling and Response. In: Developments in Volcanology. Band 10, 2005, Magma-Chamber Geometry, Fluid Transport, Local Stresses and Rock Behaviour During Collapse Caldera Formation, S. 313–349, doi:10.1016/S1871-644X(07)00008-3 (englisch).

Weblinks

- Caldera beim Global Volcanism Program ( vom 12. Januar 2014 im Internet Archive) (englisch)

- V. Camp: Calderas, How Volcanoes Work, Dept. of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University ( vom 19. April 2001 im Internet Archive) (englisch)

- Kilauea’s summit caldera collapse auf YouTube, 12. Dezember 2018, abgerufen am 15. Dezember 2023 (Zeitraffer der Entstehung der Kilauea Caldera in 2018).

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Thomas Keller: Zwischen Feuer und Wasser: Der Geologe Leopold von Buch. In: Mitteilungen des Nassauischen Vereins für Naturkunde. Band 61, 2009, S. 24 (naturkunde-online.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Frank Ahnert: Einführung in die Geomorphologie. 1996/2009, ISBN 978-3-8252-8103-8, S. 280.

- ↑ Magnús T. Gudmundsson, Kristín Jónsdóttir, Andrew Hooper et al.: Gradual caldera collapse at Bárdarbunga volcano, Iceland, regulated by lateral magma outflow. In: Science. Band 353, Nr. 6296, 2016, doi:10.1126/science.aaf8988 (englisch, whiterose.ac.uk [PDF]).

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Aerial view west across Pinatubo caldera showing fumaroles and crater lake.

Sakurajima volcano and Aira Caldera from space.

Original Caption Released with Image:

The active volcano Sakura-Jima on the island of Kyushu, Japan is shown in the center of this radar image. The volcano occupies the peninsula in the center of Kagoshima Bay, which was formed by the explosion and collapse of an ancient predecessor of today's volcano. The volcano has been in near continuous eruption since 1955. Its explosions of ash and gas are closely monitored by local authorities due to the proximity of the city of Kagoshima across a narrow strait from the volcano's center, shown below and to the left of the central peninsula in this image. City residents have grown accustomed to clearing ash deposits from sidewalks, cars and buildings following Sakura-jima's eruptions. The volcano is one of 15 identified by scientists as potentially hazardous to local populations, as part of the international "Decade Volcano" program.

The image was acquired by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C/X-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR-C/X-SAR) onboard the space shuttle Endeavour on October 9, 1994. SIR-C/X-SAR, a joint mission of the German, Italian and the United States space agencies, is part of NASA's Mission to Planet Earth. The image is centered at 31.6 degrees North latitude and 130.6 degrees East longitude. North is toward the upper left. The area shown measures 37.5 kilometers by 46.5 kilometers (23.3 miles by 28.8 miles). The colors in the image are assigned to different frequencies and polarizations of the radar as follows: red is L-band vertically transmitted, vertically received; green is the average of L-band vertically transmitted, vertically received and C-band vertically transmitted, vertically received; blue is C-band vertically transmitted, vertically received.Cataclysmic eruption to present.

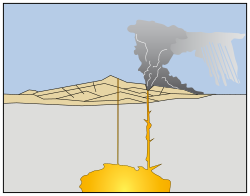

Eruptions of ash and pumice: The cataclysmic eruption started from a vent on the northeast side of the volcano as a towering column of ash, with pyroclastic flows spreading to the northeast.

Caldera collapse: As more magma was erupted, cracks opened up around the summit, which began to collapse. Fountains of pumice and ash surrounded the collapsing summit, and pyroclastic flows raced down all sides of the volcano.

Steam explosions: When the dust had settled, the new caldera was 5 miles (8 km) in diameter and 1 mile (1.6 km) deep. Ground water interacted with hot deposits causing explosions of steam and ash.

Today: In the first few hundred years after the cataclysmic eruption, renewed eruptions built Wizard Island, Merriam Cone, and the central platform. Water filled the new caldera to form the deepest lake in the United States. Figure modified from diagrams on back of 1988 USGS map “Crater Lake National Park and Vicinity, Oregon.”Autor/Urheber: Jens Steckert, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Teide and the Caldera, Tenerife. View from south (close to Guajara).

Luftaufnahme der Aniakchak Caldera mit Blick nach Osten. Der Aniakchak ist einer der spektakulärsten Vulkane auf der Alaska-Halbinsel. Entstanden während einer katastrophalen Ausbruchs vor rund 3.400 Jahren, ist die Aniakchak Caldera über 10 Kilometer (6 Meilen) breit und durchschnittlich 500 m (1.640 ft) tief. Der Vulkan ist Teil des Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve in Alaska.

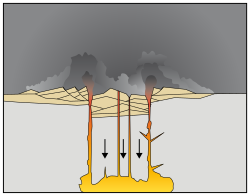

Cataclysmic eruption to present.

Eruptions of ash and pumice: The cataclysmic eruption started from a vent on the northeast side of the volcano as a towering column of ash, with pyroclastic flows spreading to the northeast.

Caldera collapse: As more magma was erupted, cracks opened up around the summit, which began to collapse. Fountains of pumice and ash surrounded the collapsing summit, and pyroclastic flows raced down all sides of the volcano.

Steam explosions: When the dust had settled, the new caldera was 5 miles (8 km) in diameter and 1 mile (1.6 km) deep. Ground water interacted with hot deposits causing explosions of steam and ash.

Today: In the first few hundred years after the cataclysmic eruption, renewed eruptions built Wizard Island, Merriam Cone, and the central platform. Water filled the new caldera to form the deepest lake in the United States. Figure modified from diagrams on back of 1988 USGS map “Crater Lake National Park and Vicinity, Oregon.”Lake Toba, Sumatra, Indonesia - Landsat satellite photo

The volcano’s most distinctive feature, its nine-kilometre wide caldera, Cha Caldera, is shown in this image. The crater wall in the west towers one kilometre above the crater floor. The eastern half of the crater wall is gone, erased in a massive collapse deep in its ancient history. Evidence of the volcano’s more recent eruptive history is written on the surface of the crater as well. In the centre of the crater, a steep cone named Pico rises about 100 meters above the crater rim (more than a kilometre from the crater floor). The young peak reaches 2,829 meters above sea level, making it the island’s highest point. Dark trails of hardened lava from the volcano's most recent eruptions stream out of the crater east into the Atlantic Ocean. The volcano last erupted in 1995. The sepia stream of lava from that eruption is pooled near the crater rim west of Pico. Remarkably, the crater is inhabited. A straight road cuts between the crater wall and Pico, ending near the vent that erupted in 1995. Bright white dots on the north side of the crater are villages. Residents of the Cha Caldera evacuated during the eruption.

Halemaʻumaʻu Crater in Kīlauea, Hawaii

* Left: April 13, 2018

* Right: July 28, 2018

Here's another "then and now" look at Halema‘uma‘u (view is to north). At left, Halema‘uma‘u, as we once knew it, and the active lava lake within the crater are visible on April 13, 2018. At right is a comparable viewshed captured on July 28, 2018, following recent collapses of the crater. The Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park Jaggar Museum and USGS-HVO can be seen perched on the caldera rim (middle right) with the slopes of Mauna Loa in the background.

Olympus Mons, a Martian volcano, photographed by the Viking 1 spacecraft from 5000 miles away

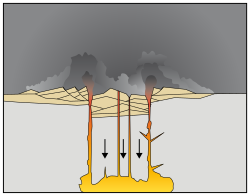

Cataclysmic eruption to present.

Eruptions of ash and pumice: The cataclysmic eruption started from a vent on the northeast side of the volcano as a towering column of ash, with pyroclastic flows spreading to the northeast.

Caldera collapse: As more magma was erupted, cracks opened up around the summit, which began to collapse. Fountains of pumice and ash surrounded the collapsing summit, and pyroclastic flows raced down all sides of the volcano.

Steam explosions: When the dust had settled, the new caldera was 5 miles (8 km) in diameter and 1 mile (1.6 km) deep. Ground water interacted with hot deposits causing explosions of steam and ash.

Today: In the first few hundred years after the cataclysmic eruption, renewed eruptions built Wizard Island, Merriam Cone, and the central platform. Water filled the new caldera to form the deepest lake in the United States. Figure modified from diagrams on back of 1988 USGS map “Crater Lake National Park and Vicinity, Oregon.”Cataclysmic eruption to present.

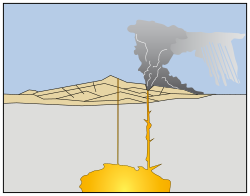

Eruptions of ash and pumice: The cataclysmic eruption started from a vent on the northeast side of the volcano as a towering column of ash, with pyroclastic flows spreading to the northeast.

Caldera collapse: As more magma was erupted, cracks opened up around the summit, which began to collapse. Fountains of pumice and ash surrounded the collapsing summit, and pyroclastic flows raced down all sides of the volcano.

Steam explosions: When the dust had settled, the new caldera was 5 miles (8 km) in diameter and 1 mile (1.6 km) deep. Ground water interacted with hot deposits causing explosions of steam and ash.

Today: In the first few hundred years after the cataclysmic eruption, renewed eruptions built Wizard Island, Merriam Cone, and the central platform. Water filled the new caldera to form the deepest lake in the United States. Figure modified from diagrams on back of 1988 USGS map “Crater Lake National Park and Vicinity, Oregon.”