Aposematismus

Aposematismus, gelegentlich auch Warnfärbung genannt, bezeichnet in der Verhaltensbiologie die auffällige Färbung von Tieren, mit der potentiellen Fressfeinden nicht nur Präsenz, sondern auch Ungenießbarkeit und/oder Wehrhaftigkeit signalisiert wird. Aposematismus ist damit das Gegenteil der Tarnung. Andererseits verschwimmen, aus der Ferne betrachtet, die Konturen von Warnzeichnungen und können dann bei einigen Tieren einer Tarnfärbung entsprechen.[1]

Einige durchaus genießbare und nicht wehrhafte Arten bilden die Merkmale aposematischer Arten nach, um potenzielle Feinde abzuschrecken. Diese Strategie wird als Mimikry bezeichnet.

Beispiele

Aposematisch gefärbte Tiere sind entweder wehrhaft, weil sie Giftstacheln besitzen oder über andere aktive Abwehrmechanismen verfügen, oder sie schmecken unangenehm, sind ungenießbar oder gar giftig. Meist ist eine einzige Begegnung ausreichend, damit potentielle Fressfeinde eine lebenslange Abneigung gegenüber aposematisch gefärbten Tieren entwickeln. Insbesondere bei Schmetterlingsraupen findet man neben gut getarnten Raupen auch solche, z. B. die Raupe der Erlen-Rindeneule, die ihre Ungenießbarkeit über eine auffällige Färbung signalisieren. Weitere Beispiele sind die Kugelfische, Muränen, Pfeilgiftfrösche und auch einige heimische Amphibien wie zum Beispiel Feuersalamander und Unken. Giftige Kraken können ihren Aposematismus bei Bedarf noch steigern, indem Muskelzellen die Warnmuster zusätzlich pulsieren lassen, so bei den Blaugeringelten Kraken.[2]

Da Fressfeinde in der Regel die Abneigung gegenüber aposematisch gefärbten Arten lernen müssen, werden immer wieder Individuen einer solchen Art verletzt oder sogar gefressen. Sie dienen als ‚Lehrmodell‘ des Fressfeindes. Diese Kosten der auffälligen Färbung – der Verlust einzelner Tiere – wird jedoch durch den so erworbenen Schutz der anderen Individuen einer Population überkompensiert.

Entstehung

2025 hat eine internationale Forschergruppe untersucht, welche Faktoren dazu führen, dass die Individuen mancher Arten Fressfeinde mit auffälligen Farben vor einem Angriff warnen, während die Individuen anderer Arten sich durch Tarnung – eine gegensätzliche Überlebensstrategie – vor Fressfeinden verstecken.[3] In einem Begleittext der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Studie hieß es, „dass die Räubergemeinschaft den größten Einfluss hat. In Gebieten mit starker Konkurrenz unter Räubern war Tarnung erfolgreicher, da die Räuber eher bereit waren, das Risiko einzugehen, potenziell giftige Beute anzugreifen. Kryptische Strategien funktionierten jedoch nicht immer. In hellen Lebensräumen waren getarnte Beutetiere besser sichtbar und wurden häufiger angegriffen als Beutetiere mit klassischen Warnfarben. Und wo Tarnung weit verbreitet war, wurden Räuber besser darin, sie zu erkennen, wodurch ihre Wirksamkeit verringert wurde.“[4]

Die evolutionäre Entwicklung des Aposematismus ist bislang ungeklärt: Eine Warnfärbung, die durch eine Mutation erstmals bei einem Individuum auftritt, erhöht im Vergleich zu getarnten Individuen ihr Prädationsrisiko. Ein Erklärungsansatz ist, dass sich zuerst die Ungenießbarkeit oder Wehrhaftigkeit ausbildet und erst bei höheren Populationsdichten Warnfärbungen entwickeln.

Galerie

- Tigermuräne

- Großer Blaugeringelter Krake (Hapalochlaena lunulata)

- Larve der Erlen-Rindeneule

Belege

- ↑ James B. Barnett, Innes C. Cuthill, Nicholas E. Scott-Samuel: Distance-dependent aposematism and camouflage in the cinnabar moth caterpillar (Tyria jacobaeae, Erebidae). In: Royal Society Open Science. Band 5, Nr. 2, 2018, Artikel 171396, doi:10.1098/rsos.171396, (PDF).

- ↑ Yfke Hager: Blue-ringed octopus flexes muscles to flash fast warning signals. In: The Journal of Experimental Biology. Band 215, Nr. 21, 2012, doi:10.1242/jeb.080598.

- ↑ Iliana Medina et al.: Global selection on insect antipredator coloration. In: Science. Band 389, Nr. 6767, 2025, S. 1336–1341, doi:10.1126/science.adr7368.

- ↑ Warnfarbe oder Tarnung: Studie enthüllt, warum manche Tiere grell leuchten und andere vor aller Augen verschwinden. Auf: mpg.de vom 25. September 2025.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

(c) Christian Fischer, CC BY-SA 3.0

Vergleich der Bauchseiten der beiden in Mitteleuropa vorkommenden Unkenarten Rotbauchunke (oben) und Gelbbauchunke (unten). Bei beiden handelt es sich um Jungtiere, die vom Fotografen auf den Rücken gedreht wurden, um ihre farbige und gemusterte Bauchseite demonstrieren zu können.

Arothron meleagris

Autor/Urheber: Patrick Gijsbers, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Granulated poison arrow frog

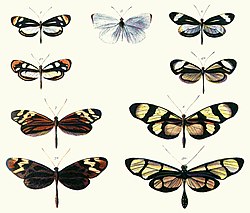

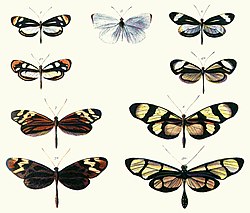

Plate illustrating Batesian mimicry between Dismorphia species (top row, third row) and various Ithomiini (Nymphalidae) (second row, bottom row)

Plate LVI.

Fig. 1. Leptalis Theonoë, var. Erythroë.— St. Paulo, 69° W. long.

Fig. 2. Leptalis Theonoë, var. Erythroë.— St. Paulo.

Fig. 3. Leptalis Theonoë, var. Erythroë.— St. Paulo.

Fig. 3 a. Ithomia Orolina, var. Chrysodonia.— St. Paulo. The linking variations between L. Erythroë and Theonoë can be traced through the varieties 8, 5, and 6 of the preceding Plate. The substitution of red for white in the fore wings is seen to be a simple variation. Some traces of the narrowing of the red margin of the hind wing are also seen. The imitation of Ithomia is not nearly so close as it is in the cases of figs. 1 and 2 of the preceding and fig. 4 of the present Plate, but there is a considerable approximation, giving the appearance of a striving after a correct imitation. The selection of individuals having the most faithful likeness is here either not rigid or we see the formation of an exact mimetic analogue in process.

Fig. 4. Leptalis Theonoë, var. Leuconoë.— St. Paulo.

Fig. 4a. Ithomia Ilerdina (Hewitson).— St. Paulo. This Leptalis appears at first sight an absolutely distinct species, but it is plainly a modification whose adaptation is complete. As to the fore wings, the vacillating nature of the colours is seen in figs. 4, 6, and 8 of Plate LV. in the clearest manner. The hind wings appear very peculiar, on account of the milky colour; but this is shown to arise by variation in Ithomiæ, which exhibit all the grades of variation from dusky to white nervures and ground of the hind wing.

Fig. 5. Leptalis Nehemia (of authors). — New Granada and S. Brazil. Figured to show the normal form of the family (Pieridæ, called in England "Garden White" Butterflies) to which Leptalis belongs. The contrast in form and colours points to the conclusion that all the other forms of Leptalis are perverted from the usual facies of the family by long-continued process of adaptation to the Heliconidæ, in whose company (each species with its Heliconian model) they are solely found.

Fig. 6. Leptalis Theonoë, var. Argochloë. — St. Paulo.

Fig. 6 a. Ithomia Virginia (Hewits.). — St. Paulo. The links of modification may be traced also with respect to this apparently distinct Leptalis. The shape of the spot of the fore wing is seen to be very variable in figs. 1, 2, 3 of this Plate, and in 9 and 4 of Plate LV.

Fig. 7- Leptalis Amphione, var. Egaëna. — Ega.

Fig. 7a. Mechanitis Polymnia, var. Egaënsis. — Ega.

Fig. 8. Leptalis Orise (Boisduval). — Cuparí, 55° W. long.; also Cayenne.

Fig. 8a. Methona Psidii (Linnæus). — Cuparí; also Cayenne.

— Bates, Henry Walter, in: [1]

Autor/Urheber: Jens Petersen, Lizenz: CC BY 2.5

Image of a Greater blue-ringed octopus. Hapalochlaena lunulata. Taken at Tasik Ria, North Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Autor/Urheber: Philippe Guillaume, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Enchelycore anatina - Fangtooth moray / Picopato / Murène tigrée, Tenerife.

Autor/Urheber: Gionorossi, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Estação Ecológica de Santa Bárbara de nível Estadual, localizado (a) em Águas de Santa Bárbara (SP)

Autor/Urheber: Lebrac, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Larve der Erlen-Rindeneule, Acronicta alni

Fire salamander found near Queralbs (Spanish Pyrenees)