Tee-Pferde-Straße

Die Tee-Pferde-Straße (chinesisch 茶馬道 / 茶马道, Pinyin Chámǎdào, auch茶馬古道 / 茶马古道, Chámǎgǔdào – „Alte Tee-Pferde-Straße“) war ein Handelsweg zwischen den chinesischen Provinzen Yunnan (云南) und Sichuan (四川) im Osten und Tibet und Indien im Westen. Manchmal wird sie auch Südliche Seidenstraße genannt. Von den zahlreichen Teerouten, die von den Teeanbaugebieten in diesen beiden Provinzen in alle Himmelsrichtungen führten, hatte sie die größten landschaftlichen Hindernisse zu überwinden. Sie kreuzte mehrere Gebirgskämme von bis zu mehr als 4000 Meter Höhe und mehrere große Flüsse. Acht Monate pro Jahr war sie wegen verschneiter Pässe unterbrochen.

Geschichte

Im 7. bzw. 8. Jahrhundert kamen die Tibeter auf den Geschmack von sogenanntem Ziegeltee aus Yunnan. Als Tauschware bot man Pferde, da diese in Teilen Südchinas äußerst rar waren. Ein Kriegspferd hatte den Gegenwert von 20 bis 60 kg Tee. So kam in der Tang-Dynastie (618–907) der Handel zwischen Tibet und Yunnan in Schwung.

Seine Blüte hatte er in der Song-Zeit (960–1279), als Kontrollposten bis zu 2000 Händler am Tag zählten und teilweise um die 7.500 Tonnen Tee pro Jahr nach Lhasa gebracht wurden.

Unter der mongolischen Herrschaft (Yuan-Dynastie, 1279–1368) brach der Handel etwas ein. Unter den Ming-Kaisern (1368–1644) erholte er sich wieder, wurde aber zunehmend reglementiert.

Die Mandschu-Herrscher (Qing-Dynastie 1616–1912) schließlich verboten 1735 den Import von Pferden. Und als nach 1840 die Teeproduktion in Indien in Gang kam, ging das Land südlich des Himalaya als Markt für chinesischen Tee verloren, Tibet aber nicht. Mit dem Bau von Landstraßen in Tibet in den 1960er Jahren endete der Karawanenverkehr.[1][2]

Waren

Die wichtigsten Güter waren Tee aus China, von dem der größere Teil nach Tibet und der kleinere Teil nach Indien ging, und Pferde aus Tibet, die in China vor allem für die Armee (im Süden des Reiches) gebraucht wurden. Der Teehandel erklärt sich daraus, dass es vor 1830 in Indien noch keinen Teeanbau gab. Tibet bezog zudem Salz aus China. Transportiert wurden auch Seide aus China und Opium nach China.

Routen

Genau genommen bestand die Tee-Pferde-Straße zu einem großen Teil aus Saumpfaden und hatte mehrere Varianten. Pferde wurden zwar als Ware über diese Pfade geführt, aber als Lasttiere dienten wie in vielen anderen Gebirgsregionen Maultiere. Nicht wenige Karawanen bestanden aus Trägern.

Die nördlichen Routen, von Chengdu in Sichuan nach Westen und aus Dali (大理) in Yunnan nach Nordwesten, vereinigten sich im Kreis Markam (tibetischསྨར་ཁམས; chinesisch 芒康, Pinyin Mángkāng) im Osten Tibets in Chengguan (tib.ཆབ་མདོ་) am Oberlauf des Mekong und führten von dort südlich des Oberlaufs des Saluen nach Lhasa (ལྷ་ས་). Von dort ging es über Gyangzê (རྒྱལ་རྩེ) und den Pass Nathu La (རྣ་ཐོས་ལ་) durch Sikkim nach Kalkutta in Bengalen. Von Chengdu oder Dali waren es bis Lhasa etwa 2000 km, bis Kalkutta etwa 3000 km, aus den Hauptteeanbaugebieten im Süden und Osten Yunnans noch ein paar hundert Kilometer mehr.

Weniger stark benutzt wurden die südlichen Routen nach Indien, die von Dali durch den Norden Myanmars, Nagaland und das Brahmaputra-Ganges-Delta Kalkutta erreichten. Sie waren zwar kürzer und passierten geringere Höhen als die nördlichen, dafür aber mehr Grenzen und die Gebiete unkontrollierter Bergvölker. Und Tibet lag abseits dieser Routen. Da Tibet der Pferdeexporteur war, sind sie nicht der Tee-Pferde-Straße zuzurechnen.

Nördliche wie südliche Routen vermieden das besonders unwegsame Gebirge Hengduan Shan (横断山).

Weblinks

- YANG, Fuquan: The “Ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Road,” the “Silk Road” of Southwest China. In: silkroadfoundation.org. Silkroad Foundation (englisch).

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ YANG, Fuquan: The “Ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Road,” the “Silk Road” of Southwest China. In: silkroadfoundation.org. Silkroad Foundation, abgerufen am 3. November 2018 (englisch).

- ↑ ZHANG, Yun: THE TEA-HORSE TRADE ROUTE. In: the-wanderling.com. Abgerufen am 3. November 2018 (englisch).

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

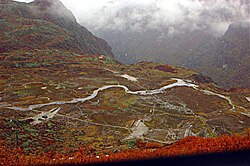

Autor/Urheber: Jaryiahr Khan, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Melong valley near Chamdo town, downstream of it (conluded from original desciption "South of Chamdo (Qamdo) town, Chamdo County, Tibet")

Autor/Urheber: Ulamm, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Map of the ancient Tea and Horses Road without names, so that the names can be added in any spelling or characters.

The Tea-(and)-Horse(s) route from Yunnan and Sichuan to Tibet and Bengal was one of the ancient Tea routes, with variants itself. The courses are drawn according to a combination of informations from Chinaexpat: The ancient Tea-Horse-Road, and informations from Andrées Weltatlas from 1880, printed, when the route was a main traderoute, still.

Autor/Urheber: ralph repo, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Entitled: Two Men Laden With Tea, Sichuan Sheng China, 30 JUL [1908] EH Wilson [RESTORED] Very little retouching except for a few scratches and spots. Minor contrast and sepia tone added. The original resides in Harvard University Library's permanent collection, and can be found using their Visual Information Access (VIA) Search System by using the title.

Ernest Henry "Chinese" Wilson was an explorer botanist who traveled extensively to the far east between 1899 and 1918, collecting seed specimens and recording with both journals and camera. About sixty Asian plant species bear his name. One of his most famous photographs (above) has repeatedly been mistakenly attributed to another legendary botanist (Joseph Rock) who was also working in Asia.

From Wilson's personal notations (with misspellings as is):

"Men laden with 'Brick Tea' for Thibet. One man's load weighs 317 lbs. Avoird. The other's 298 lbs. Avoird.!! Men carry this tea as far as Tachien lu accomplishing about 6 miles per day over vile roads, 5000 ft."

I suspect that Wilson made a mistake; either miscalculating a conversion from Chinese Imperial to European weight measure, or that he believed an inflated figure offered him by a less than honest native. However, others purportedly shared the same beliefs that some porters did in fact, carry upwards of 300 pound loads. In a rare 2003 interview with several retired former porters, still alive and in their 80's. They stated that while the average was really more between 60-110 Kg; they acknowledged that some (only the very strongest) could shoulder a superhuman 150 Kg load; someone like Giant Chang Woo Gow, or one of his kin, perhaps? An excerpt about that interview:

"The Burden of Human Portage

As recently as the first decades of the 20th century, much of the tea transported by the ancient Tea-Horse Road was carried not by mule caravan, but by human porters, giving real substance to the once widely-employed designation ‘coolie’, a term thought to have been derived from the Chinese kuli or ‘bitter labour’. This was particularly true of smaller tracks and trails leading from remote tea-picking areas to the arterial Tea-Horse routes, both in Yunnan and in Sichuan. Perhaps because this human portage played a less economically significant role than the large – sometimes huge – yak, pony and mule caravans, and perhaps because there is little or no romance attached to the piteous sight of over-burdened, inadequately-clad and under-nourished porters hauling themselves and their massive loads across muddy valleys and freezing mountain passes, less information is available to us concerning tea porters than about tea caravans.

Fortunately some black-and-white images of these incredibly wiry, tough, hard-bitten men have come down to us from Sichuan, as well as at least one 150-year-old French-made lithograph from Yunnan, in addition to some rare oral accounts describing the immense difficulties these hardy wretches had to face. In the latter category, as recently as 2003 China Daily carried an interview with four former tea porters in Ganxipo Village, near Tianquan County to the southwest of Ya’an. Now in their 80s, these veterans recall hard times before the completion of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway in 1954 when they would carry almost impossibly heavy loads of Sichuan Pu’er tea over a narrow mountain trail across the freezing heights of Erlang Shan (‘Two Wolves Mountain’) to Luding and onwards, across the Dadu River, to the tea distribution centre at Kangding.

According to 81-year-old former tea porter Li Zhongquan, tea was carried by human portage all the way from Tianquan County to Kangding, a distance of 180km (112 miles) each way on narrow mountain tracks, much of the way at dangerously high altitudes in freezing temperatures. According to Li, an able-bodied porter would carry 10 to 12 packs of tea, each weighing between 6 and 9 kg. To this had to be added 7 to 8 kg of grain for sustenance en route, as well as ‘five or six pairs of homemade straw sandals to change on the way’. The strongest porters could carry 15 packs of tea, making a total load of around 150 kg (330 imperial pounds). ‘The grain lasted no longer than half the journey’, Li remembered, ‘and you had to replenish your food supply at your own expense’. As for the multiple pairs of straw sandals: ‘these would be worn out quickly, as the mountain path was extremely rough’.

To make the portage of such heavy loads possible, and to help guard against the ever-present danger of overbalancing and falling into one of the many deep ravines skirted by the narrow mountain trail, tea porters carried iron-tipped T-shaped walking sticks both to assist in struggling over the steep, rocky path, and to rest the load on, without taking it off their backs, when they paused for breath. A surviving section of the old stone path near Ganxipo Village bears testament to the almost unimaginable difficulties faced by the tea porters in the past; small holes dot the stone slabs of the path at regular intervals of a pace or so, indicating where, over centuries and perhaps even millennia, the porters struck the rock with their iron-tipped sticks as they made their laborious way to and from Kangding.

It is possible to identify the T-shaped walking-and-support sticks used by the tea porters in black and white photographs from a century or more ago, including one taken by the American explorer and botanist E.H. Wilson, who helpfully appends the information: ‘Western Szechuan; men laden with “brick tea” for Thibet. One man's load weighs 317 lbs [144 kilos], the other's 298 lbs [135 kilos]. Men carry this tea as far as Tachien-lu [Kangding] accomplishing about six miles per day over vile roads. Altitude 5,000 ft [1,500m] July 30, 1908’.

For the tea porters of Ganxipo Village, the hardest part of their journey was the climb over Erlang Shan. The precipitous mountain trail was so narrow that it was only wide enough for one person to pass at a time. According to Li Zhongquan: ‘one misstep, and you were gone – we had our sandals soled with iron to get over the mountain’. Li also remembers when: ‘one of us was sick and fell dead on the mountain top in winter. We had to leave him there until the snow thawed in spring, when we carried the body down home’. The porters carried tea from Tianquan to Kangding, and returned with loads of medicinal herbs (especially Cordyceps sinensis of Chinese caterpillar fungus), musk, wool, horn and other Tibetan products. The four porters interviewed in China Daily did not know for sure when the tea portage trade had started in Ganxipo, but Li was certain that ‘my grandpa’s grandpa was a porter as well,’ and that the whole village had offered porter services for generations."

Source:[www.cpamedia.com/trade-routes...l-perspective/] Author: Andrew Forbes, David Henley, China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2 (Source (of book quote) information received via OTRS Ticket:2012091010014712. Rjd0060 (talk) 13:02, 11 September 2012 (UTC)

Just walking for a few kilometers on a flat surface with 40 Kg worth of material on your back, I can attest is already exhausting. To imagine tripling that weight, walk for over 180 kilometers over mountain trails, and breathe rarefied air? I wouldn't say it's downright impossible, but highly improbable. I too, would agree that it was likely only exceptions rather than the rule.Autor/Urheber: Redgeographics, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 4.0

Map of the Tea-Horse road

Autor/Urheber: Taco Witte, Lizenz: CC BY 2.0

Pu-erh tea shown at the front is originally from this region. At the back is a Buddha statue overseeing the valley and a stupa that can be seen from a great distance on both sides. This photo was taken close to Xiding.